Love makes us vulnerable. It roots our happiness in the life of another, bringing us outside of ourselves and placing all our hopes and joys in those whom we love. The bond of love makes two become one: lovers rejoice in each other’s presence, sharing each other’s joys, each one living, as it were, through the life of the other. But because of this shared life, love also opens our hearts to new possibilities of suffering: fearing the pain that the loved one may experience, agonizing in the other’s affliction, and grieving that one’s absence. A mother’s heart is especially vulnerable to this kind of suffering, for with every birth comes the potential for love and for loss.

We can see this vulnerability play out in the lives of two different mothers: Kristin, the heroine of Sigrid Undset’s Kristin Lavransdatter, and Sarah, the wife of Abraham (as depicted by an anonymous Syriac poet). Kristin experiences her intense love for her sons as a death sentence. The potential suffering and loss of her children constantly plagues her soul, casting her into unbearable anguish, and she fears that she would not be able to survive such a loss. Sarah, on the other hand, is somehow able to endure what seems to be the death of her only beloved son, Isaac. The difference between the two is that Kristin taints her love with self-centered desires of possession and pride, while Sarah faithfully surrenders her own motherly love to God’s loving providence. Sarah’s love is the only kind of love that can bear the trials of motherhood. Trusting in God’s love in all things, Sarah foreshadows Mary, the Mother of God, who shines as an example for all sorrowful mothers.

Kristin: Every Mother’s Fear

Kristin is haunted by a recurring dream that captures both her deep longing for her children and her greatest fear: that she will be unable to protect them from the evils of the world.

She saw a meadow with flowers, a steep hill deep inside a pine forest, dark and dense… Halfway up the slope, standing deep in the avalanche of alpine catchflies and globeflowers and the pale green clouds of angelica, she saw her child… (Undset, 853)

As dream-Kristin sits and watches her son playing in the flowers, her heart feels both an aching sweetness at the loveliness of her child and a clutch of dull anguish, some premonition of an impending evil. Then, it happens.

…she sees emerging from the darkness at the edge of the woods a furry bulk that is alive. It moves soundlessly, its tiny, vicious eyes smouldering. The bear reaches the top of the meadow and stands there, its head and shoulders swaying, as it considers the slope. Then it leaps. Kristin had never seen a bear alive, but she knew bears didn’t leap that way. This is not a real bear. It runs like a cat; at the same moment it turns gray, and like a giant light-colored cat it flies with long, soft strides down the hill. (Undset, 853)

The mother now is thrown into a deathly fright, unable to reach the child to protect him, unable to speak or shout a word of warning. In her helplessness, she must simply watch the terror that unfolds.

Then the boy notices that something is there; he turns halfway and looks over his shoulder. With a horrifying, low-pitched cry of terror he tries to run downhill, lifting his legs high in the tall grass the way children do. And his mother hears the tiny crack of sap-filled stalks breaking as he runs through the profusion of blossoms. Now he stumbles over something in the grass, falls headlong, and in the next instant the beast is upon him with its back and its head lowered between its front paws. Then she wakes up. (Undset, 853)

For hours, Kristin would lie awake, trying to reassure herself, cradling her youngest child between her arms, practically crushing him in the embrace. She would tell herself that if it had been real she could have done this or that, anything, to scare of the beast.

But just when she had convinced herself in this manner to calm down, it would seize hold of her once again: the unbearable anguish of her dream as she stood powerless and watched her little son’s pitiful, hopeless flight from the strong, ruthlessly swift, and hideous beast. Her blood felt as if it were boiling inside her, foaming so that it made her body swell, and her heart was about to burst, for it couldn’t contain such a violent surge of blood. (Undset, 853)

Kristin has a fierce love for her sons. But when faced with her own inability to protect her children, she is overwhelmed by the fear of losing them. Her fear grows into a paralyzing despair as she sees that she is unable to endure such a loss. This despair ravages her soul and imprisons her heart in constant anguish. While Kristin gives all her strength to protecting the wellbeing of her sons, she is interiorly plagued by “a secret, breathless anguish: If things go badly for them, I won’t be able to bear it.”

Kristin is grieved and perplexed by her memory of her own mother and father, who over the years suffered the tragic death of many of their children. Though this submitted them to intense suffering, they had somehow managed to bear the weight: “They had borne anguish and sorrow over their children, day after day, until their deaths; they had been able to carry this burden, and it was not because they loved their children any less but because they loved with a better kind of love” (Undset, 854). In comparing her parents with herself, Kristin sees that there is a love that can bear sorrow and loss, and a love that cannot.

Kristin is unable to endure the agonies that come with motherhood, for she has the wrong kind of love for her children. There are two aspects to this imperfect love. First, she desires above all else to possess and treasure her sons as her own. She has set all the hope and vitality of her heart upon cherishing her children. Second, this love is rooted in pride: she relies on her own strength to provide for the health and happiness of her children, struggling “to protect her sons with wings that were bound by the constraints of earthly care” (Undset, 853). In other words, Kristin has put all her hope for happiness, and all her trust in attaining that happiness, in the fate and strength of created persons. Her dream terrifies her because it attacks these two aspects of her love: it confronts her with the uncertainty of her sons’ safety, her eventually unavoidable loss of them, and her own inability to save them from evil.

This love is unable to endure the death of the beloved; because of this, its fruition is the death of the lover’s heart. Kristin sees this, and agonizes over the fate she has chosen for herself. She has put her whole heart into the lives of her children, and when her sons are taken from her, her heart will go with them, while somehow leaving her behind. Even while her sons are with her, Kristin is plunged into anguish, for she knows all too well her inability to keep them from being taken from her. Eventually, they will either leave her to live out their own lives in the world, or death will devour them. Since her heart is rooted in no other love but the love of her sons, Kristin sees that she will be unable to bear this inevitable separation. In a moment of reflection, Kristin catches a glimpse of the consequences which her earthly love holds in store for her:

Was this how she would see her struggle end? Had she conceived in her womb a flock of restless fledgling hawks that simply lay in her nest waiting impatiently for the hour when their wings were strong enough to carry them beyond the most distant blue peaks? … They would take with them bloody threads from the roots of her heart when they flew off, and they wouldn’t even know it. She would be left behind alone, and all the heartstrings, which had once bound her to this old home of hers, she had already sundered. That was how it would end, and she would be neither alive nor dead. (Undset, 854)

Sarah: Our Mother in Faith

Sarah has the “better kind of love” that Kristin sees in her parents: the love that is able to suffer the death of the beloved. We see this especially in a Syriac poem that recounts Sarah’s experience of Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac, her son. In Genesis, Sarah doesn’t appear in this part of the story. However, in the fourth and fifth centuries, some Syriac Christian authors wrote poems that filled in narrative gaps in Scriptures, retelling many of the Biblical stories from points of view that were hidden in the inspired texts (see Sebastian P. Brock, “Creating Women’s Voices: Sarah and Tamar in Some Syriac Narrative Poems.” In The Exegetical Encounter between Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity, 125-42). One of these poems gives an account of the (near) sacrifice of Isaac, but from Sarah’s perspective. Here, Sarah suffers the deep anguish of losing her only son. Unlike Kristin, however, she is able to endure this suffering, not because she loves her son less than Kristin, but because her heart is sustained by her trust in God’s loving providence. In fact, Sarah’s trust not only sustains her in difficulty, but also deepens and elevates her motherly love, moving her to love Isaac in a more powerful and eminent way.

During Abraham’s great trial of faith, God demands that Abraham offer his only-begotten son Isaac as a burnt sacrifice to the Lord. This has the potential to be a great moment of confusion for Abraham, since God had sworn to him many times that he would become the father of a great nation through the descendants of Isaac. But Abraham’s faith shines as he willingly obeys God’s command while still trusting firmly in the Lord’s promise. Abraham’s faith is rewarded: an angel is sent from heaven to prevent him from sacrificing Isaac.

In this poem, Sarah is portrayed as the true hero of the event because her faith is tested not once, as Abraham’s was, but twice. In the first trial, she shows her willingness to entrust her son entirely to God’s care by handing him over to Abraham, knowing full well her husband’s intentions. Then, in the second trial, she shows that this offering of her son was done unconditionally with a pure and selfless heart.

The poet describes how soon after God calls Abraham to sacrifice his son Sarah finds him sharpening a knife. At this sight, her heart groans, and with dread she approaches her husband:

Why are you sharpening your knife? What do you intend to slaughter with it? This secret today, why have you hidden it from me?

Though Abraham is unwilling to reveal his purpose to her, Sarah perceives his intention, and cries out,

You are drunk with the love of God, who is the God of gods, and if he so bids you concerning the child you will kill him without hesitation.

Despite her anguish, Sarah does not try to convince Abraham to disobey God, but rather begs that she be able to accompany him to the place of sacrifice, so she can be with her only son as he dies.

If you are going to bury him in the ground, I will dig the hole with my own hands, and if you are going to build up stones, I will carry them on my shoulders; the lock of my white hairs in old age will I provide for his bonds.

But even this is denied her; it is not for Sarah to accompany her son in his final hour. Though her heart is tortured, Sarah accepts this, and tearfully embraces both husband and son, uttering in prayer, “Go in peace: may God who gave you to me return you to me in safety.” Then, taking Isaac by his right hand, she hands her only son over to Abraham, as if she were entrusting her child to God Himself.

The poem concludes with Sarah’s second test. Upon arriving home from the mountain, Abraham at first hides Isaac from Sarah, saying,

My son, please stay back for a little: I will go in and return to your mother, and I will see how she receives me. I will spy out her mind and her thought.

Abraham’s purpose in this is to see if Sarah truly offered her son to God, or if she did so merely on the condition that Isaac be preserved from harm. As Abraham enters his home, alone, Sarah rises up to receive him, bringing him a bowl to wash his feet and greeting him with these words:

Welcome, blessed old man, husband who has loved God; welcome, O happy one, who has sacrificed my only child on the pyre; welcome, O slaughterer, who did not spare the body of my only child.

Overwrought with grief, Sarah implores Abraham to relate the whole event:

Did he weep when he was bound, or groan as he died? Was he greatly looking out for me? But I was not there to come to his side. His eyes were wandering over the mountains, but I was not there to deliver him. By the God whom you worship, relate to me the whole affair.

In reply, Abraham gives a cursory description of Isaac’s death: there was no groaning, no weeping, but yes, as he died he asked to see his mother. At this, Sarah is thrown into a great lament: if only she could visit the site of her only son’s death, to see his ashes, to recover some of his blood, his hair, so that their smell and sight might comfort her in her suffering! But despite her great grief, Sarah never curses God or Abraham for what has happened to her son, and at last her second trial comes to an end:

As she stood there, her heart mourning, her mind and her thought intent, greatly upset with emotion, her mind dazed as she grieved, the child returned, entering safe and sound. Sarah rose up to receive him, she embraced him and kissed him amid tears, and began to address him as follows: “Welcome, my son, my beloved, welcome, child of my vows; welcome, O dead one come to life!”

Kristin and Sarah: Two Kinds of Love

Sarah’s trials force her to endure the fate that Kristin fears, experiencing in reality the terror of Kristin’s dream. However, where Kristin crumples in weakness, Sarah endures with strength, and the source of this strength is her “better kind of love.”

Sarah’s love is better because it is selfless and rooted in faith, its purity revealed in a time of trial. In her response to God’s requests, she shows a heart unstained by the two vices that warp Kristin’s love: self-reliant pride and overly-possessive desire. By handing Isaac over to Abraham, Sarah surrenders her power of motherly protection to God’s providential hands; and by receiving her husband with love, she unconditionally accepts God’s will over her own desires. Sarah’s faith transforms and deepens her love for Isaac. By surrendering Isaac to the love of God, Sarah’s maternal love receives its strength from God’s divine fatherly love. Unlike Kristin, whose love is constrained to the limits of the earth, Sarah loves Isaac with a love that knows no bounds.

Faith is at the heart of Sarah’s selfless love. Because she believes in God’s love for His people, Sarah is able to surrender everything that she loves. This faith is neither blind nor spontaneous. She does not just generally hope that things will all work out for the best. Rather, her faith is a specific response to the covenantal promise that God gave to her: that she would be the mother of a great nation through the descendants of Isaac (Gen 17:16). God tests Sarah’s trust in this promise by confronting her with a terrible mystery: God Himself demands the death of the boy Isaac. In doing this, God is looking for Sarah to trust in Him unconditionally. He asks Sarah to suffer because He wants her to know the surety and power of His love. He wants her to know that even if all that she loves on earth should be taken from her heart, He would remain there with her. He wants her to know that, in the darkest hour, He will provide for those whom He loves.

By asking for her son, God seems to reduce Sarah again to a barren wife, a mother void of motherhood. It is her trust that enables her to survive what destroys Kristin: even when all created things are taken from her, her heart remains firm in the knowledge of God’s love. Sarah’s faith does not take away the suffering of losing her son, but it situates her suffering within the providential love of God. Such a trial would have destroyed Kristin, who put her whole heart into her children. However, Sarah is able to endure this crisis because her heart was strengthened by her faith.

Sarah’s faith allows her not just to endure suffering, but to receive the reward that God has promised. With a heart purified by her surrender to God’s will, Sarah now receives Isaac as one risen from the dead. The Syriac writer seems to apply to Sarah what is said of Abraham, who “considered that God was able to raise men even from the dead; hence he did receive [Isaac] back” (Heb 11:19). From the depths of her suffering, God brings her to a new moment of motherhood, where she sees Isaac not just as her own beloved son, but as the ‘child of her vows’—the child of God’s loving promise. Though Sarah’s fiat leads her through great suffering, its fruit is an abundance of life and love.

Mary: Our Life, Our Sweetness, and Our Hope

Sarah’s trial of faith foreshadows that of Mary. The Blessed Mother’s anguish over her son far exceeds that of both Kristin and Sarah. From the foot of the Cross, she sees the hideous beast of Kristin’s dream devour her little child, and, unlike with Isaac, God sends no angel to put a stop to his death. On Calvary, Mary’s heart breaks as she beholds mankind’s greatest offense against God and the seeming failure of Christ’s salvific mission. For, in this dark moment, God’s promise that her son “will save his people from their sins” (Mt 1: 21) seems an impossibility. As her only child hangs on the cross, it is as if Mary’s very motherhood is being stripped from her. The amount of pain her heart suffers in union with her son’s passion throws her into such an agony “that she would have died of the experience had she not been especially strengthened” (Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, Mother of the Saviour: And Our Interior Life, 193).

Despite this, her faith never wavers: “She sees the hand of God where even the most believing see only darkness and desolation” (Garrigou-Lagrange, 192). Like Sarah, Mary’s faith does not relieve her sufferings, but rather allows them be transfigured by grace. For, sharing in the passion of her divine son, she also shares in his fruitfulness as he merits our salvation. With Christ, Mary suffers for the salvation of souls, which makes Calvary a great paradox for our Mother of Sorrows. There, the very pain that she suffers as she loses her only son becomes the pangs of a new birth as God elevates and perfects her motherhood.

Mary gave birth to Jesus without pain: but she brings the faithful forth in the most cruel suffering. “…She can be mother of christians only by giving her Son to death. O agonising fruitfulness! … It is for [this] purpose that providence has brought her to the foot of the Cross. She is there to immolate her Son that men may have life.” (Garrigou-Lagrange, 190-1)

Every mother experiences to some degree the sufferings of Kristin, Sarah, and Mary. There are so many ways in which a mother can experience the loss of a child. But Mary is there for all suffering mothers, showing them a love that “bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things” (1 Cor 13:7). When our loved ones are wounded or taken from our sight, Mary teaches us to pray to her son on their behalf, “intra tua vulnera absconde me”: in your wounds hide me (from the “Anima Christi”). With Jesus, she has suffered for us, so that we might share her faith in his love for us.

✠

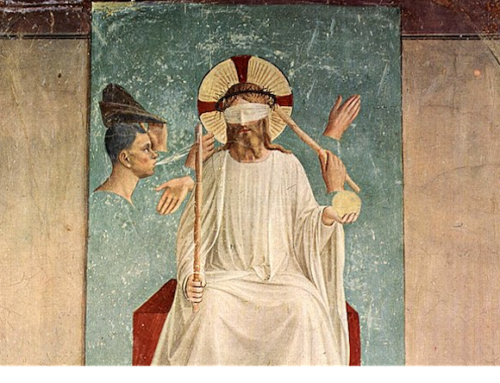

Image: Félicien Rops, Mater Dolorosa (Our Lady of Sorrows) [CC0 1.0]

Download a PDF of this article HERE