For both we and our words are in his hand, as are all understanding and skill in crafts.—Wis 7:16

Art and Ultimate Reality

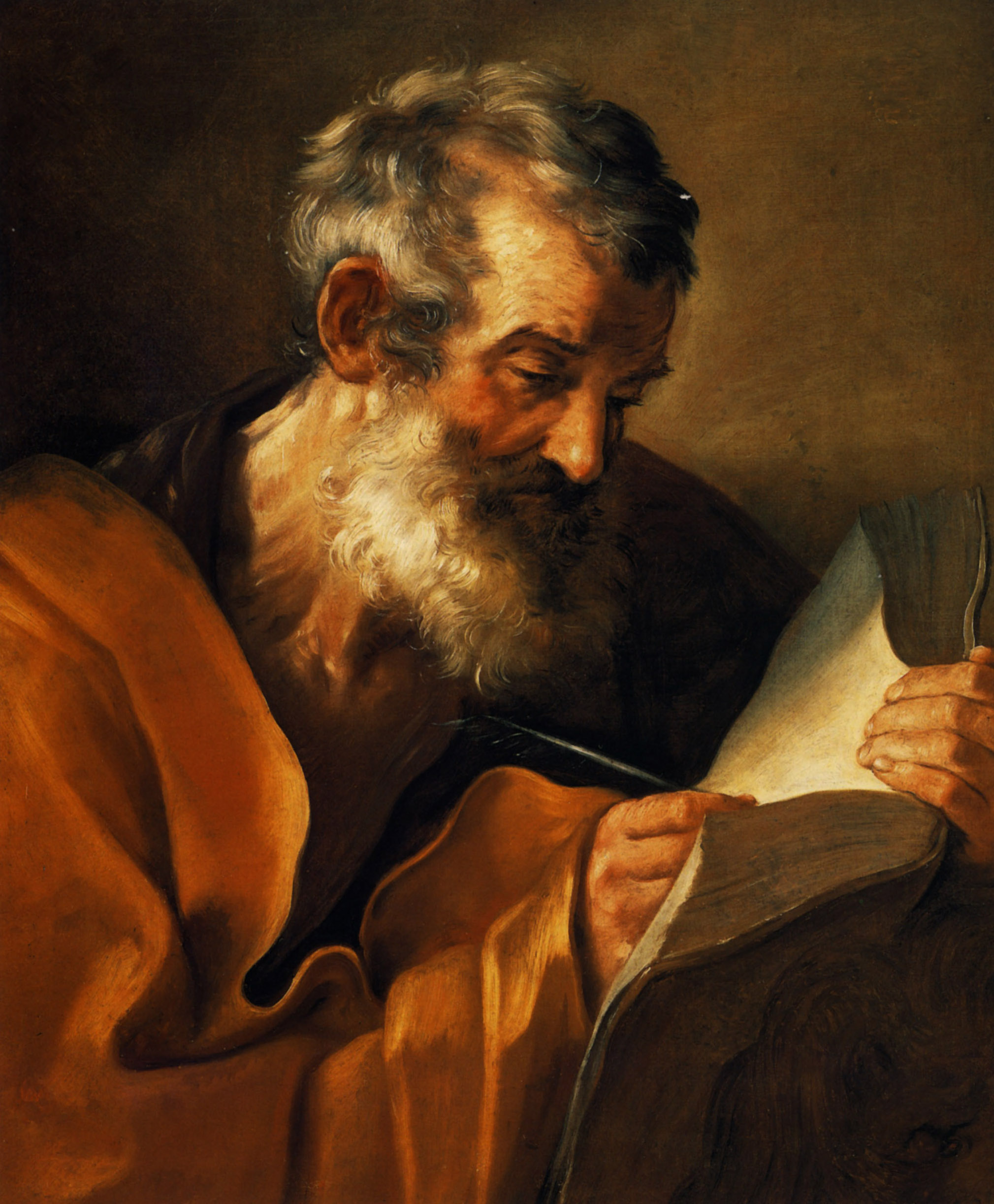

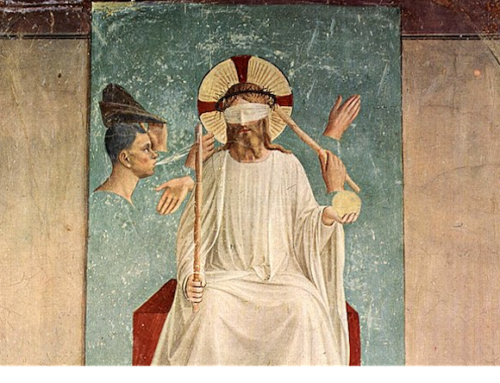

Great works of art cannot be taken in all at once. They are so rich in content, even if under the guise of simplicity, that to appreciate them takes time—usually a lot of time, or even a lifetime. And they seem to grow more beautiful the longer one beholds them, the more deeply one penetrates them. Just think of the sculptures of the anonymous ancients, the frescoes of Fra Angelico, the polyphony of Josquin and Palestrina, the drawings of Da Vinci, the cantatas of Bach, the symphonies of Beethoven, the poetry of Herbert and Hopkins, the novels of Dostoevsky and Undset, the landscapes of Monet and Van Gogh, the still lifes and portraits of Cézanne—and the Bible. How can we explain the genius behind these incomparable works of art? Perhaps unexpectedly, virtue finds its way into the picture, as it were. A work of artistic brilliance is the fruit of a specific virtue: the virtue of art.

The excellence of excellent art is at least partly due to its transcendence: art is transitory and will pass away, but it points to that which is eternal and will not. As Flannery O’Connor wrote, “[The artist] will inevitably suggest that image of ultimate reality as it can be glimpsed in some aspect of the human situation. In this sense, art reveals, and the theologian has learned that he can’t ignore it.”* Nowhere is this more true than in Scripture, whose art belongs not just to its human but also its divine provenance.

St. Thomas Aquinas and Flannery O’Connor have a great deal to say about what art is and does. As for art’s role in the dynamic of biblical inspiration, O’Connor’s insights about writing as an art and, more to the point, Aquinas’ insights about art as a virtue can tell us something about the Bible’s human authors and even something about its primary author, who is the Author not just of Scripture but of all that is.

Reason in Making

Most people who have the capacity to appreciate great art do not, it seems, have the capacity to produce it. Particularly as regards writing, Flannery O’Connor laments that the talent for it is scarcer than many people think: “Everywhere I go I’m asked if I think the universities stifle writers. My opinion is that they don’t stifle enough of them. There’s many a best-seller that could have been prevented by a good teacher. The idea of being a writer attracts a good many shiftless people, those who are merely burdened with poetic feelings or afflicted with sensibility.” Art is not simply a matter of sentiment and certainly not of arbitrary subjectivity, but of conveying truth by making something which is good and making it well. In a way, this is a simple idea, but at the same time it catapults us into the realm of the metaphysical, of reality itself, both visible and invisible. O’Connor writes:

St. Thomas called art “reason in making.” This is a very cold and very beautiful definition, and if it is unpopular today, this is because reason has lost ground among us. As grace and nature have been separated, so imagination and reason have been separated, and this always means an end to art. The artist uses his reason to discover an answering reason in everything he sees. For him, to be reasonable is to find, in the object, in the situation, in the sequence, the spirit which makes it itself. This is not an easy or simple thing to do. It is to intrude upon the timeless, and that is only done by the violence of a single-minded respect for the truth.

Art is possible only for intellectual creatures, who alone have the capacity to discover order and reason in things, to analyze and examine, and to intrude upon the timeless by a conscious and focused concern for truth. This is fairly intuitive; when we speak about great art, we recognize that the creativity of an artist’s intellect must be responsible for the form which so impresses and delights us and which can even lead us to some insight or even a sense of wonder.

The virtue of art, as an intellectual virtue, has a peculiar character in that it does not pertain to the perfection of the will, but only of the intellect. It does this by disposing the artist to make something and to do it well; and the quality of what is made is not affected by the quality of the will of the one who made it. As Aquinas points out, a good artist is praised not because of some excellence of will in his making of art, but because of the excellent quality of what he makes: when we say of an artist, “He’s good!”, we are referring to his art, not his character. In other words, art has to do with the goodness of the thing made, and not with the moral goodness of the one making it.

That Flannery O’Connor was aware of this account of the virtue of art should be no great surprise since she was something of a student of Aquinas—as she put it, “a Thomist with that ox-like look.” She once wrote, “Everybody who has read Wise Blood thinks I’m a hillbilly nihilist, whereas I would like to create the impression . . . that I’m a hillbilly Thomist”; and elsewhere, perhaps her most charming account:

I couldn’t make any judgment on the Summa, except to say this: I read it for about twenty minutes every night before I go to bed. If my mother were to come in during this process and say, “Turn off that light. It’s late,” I with lifted finger and broad bland beatific expression, would reply, “On the contrary, I answer that the light, being eternal and limitless, cannot be turned off. Shut your eyes,” or some such thing. In any case, I feel I can personally guarantee that St. Thomas loved God because for the life of me I cannot help loving St. Thomas.

All of this is to say that she knew what Aquinas said about art and was much taken with it. With relative frequency—and a hint of humility—she alluded to this virtue’s independence from moral uprightness: “St. Thomas’s remark is plain enough: you don’t have to be good to write well. Much to be thankful for . . .”

But more important here than its detachment from the rectitude of the artist’s will is the notion that the virtue of art has to do with the goodness of the thing made, and therefore with truth. Aquinas calls art “right reason of things to be made” (Summa Theologiae I-II, q. 57, a. 4)—in O’Connor’s rendering, “reason in making.” Art is seated in the intellect, which is by nature directed to truth. Hence, the “basis of art is truth, both in matter and in mode. The person who aims after art in his work aims after truth, in an imaginative sense, no more and no less.” This truth is not always immediately apparent—O’Connor was quite aware of this and saw her own works of fiction as attempts to reveal the mystery of hidden truth. She saw this as the main task of the artist, who “penetrates the concrete world in order to find at its depths the image of its source, the image of ultimate reality.” St. John Paul II later seemed almost to echo her: “Every genuine artistic intuition goes beyond what the senses perceive and, reaching beneath reality’s surface, strives to interpret its hidden mystery” (“Letter to Artists” 6). Great artists, therefore, grapple with truth and how they can present it anew, and if their art is good art, truth will be found in it. Having established this, we can now turn our gaze toward the Bible.

Scripture’s Story

In a famous letter, St. Jerome recalls the days when he took such delight in the literary works of Cicero and Plautus that the writings of the prophets seemed to him drab and boorish. When once he fell ill with a frightful fever, finding himself in such a desperate state that plans for his funeral were underway, he was ecstatically transported (and “dragged”) before the Supreme Judge, who asked him who and what he was. When he responded, “I am a Christian,” our Lord replied: Mentiris—Ciceronianus es, non Christianus. “You lie—you are a Ciceronian, not a Christian.” Struck to the heart, Jerome repented of his misplaced priorities and zealously devoted himself anew to the reading and study of the sacred page. Perhaps it was this harrowing experience that provided the impetus for his well-known later adage that “ignorance of the Scriptures is ignorance of Christ.” The Christian, of course, knows intuitively that Christ ought not to be ignored, the practical consequence being that Christians ought to know the word of God.

Throughout history, Christians and scholars (and Christian scholars) have pursued this knowledge in countless different ways. The classic identification of the literal and spiritual senses of Scripture has perdured through the centuries: “The literal sense of Scripture is that which has been expressed directly by the inspired human authors . . . [and which] is also intended by God,” whereas the manifold spiritual sense is the complementary meaning which God manifests through the human words, that is, the “meaning expressed by the biblical texts when read, under the influence of the Holy Spirit, in the context of the paschal mystery of Christ and of the new life which flows from it” (Pontifical Biblical Commission, The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church II, B, 1 and 2). Especially since the advent of modern Scripture scholarship, academic emphasis has largely been on understanding the literal sense. To this end, the proliferation of various methods of biblical criticism has been, well, prolific. The most famous modern method is historical criticism, which asks about the history behind the Bible: who wrote the biblical books and when, how did the text end up in its final form, what was happening in history at the time, and so on. But of greater relevance here is the more recent literary criticism, which includes various methods aimed at examining linguistic forms and techniques and their intended impact on the audience (rhetorical criticism), attempting to ascertain the genre of a given passage and subsequently its original setting or context (form criticism), attending to the structure of the story and various other aspects of the plot (narrative criticism), and so on. In short, literary criticism, true to its name, analyzes the Bible as a work of literature.

The Bible is not just any work of literature, of course, as if Revelation the biblical book and “Revelation” the Flannery O’Connor short story were somehow equals. We cannot remain on the level of literature for sound and thorough biblical exegesis because we would not be able to reach in any robust way to the Bible’s Christocentrism, which is its deepest meaning. Christ rebuked St. Jerome not so much because he enjoyed the literature of Cicero but because he neglected Christ. To ignore the centrality of Christ in Scripture, thereby ignoring all of the spiritual senses and even at times the literal sense, is to do the same. And this deserves the same rebuke: non Christianus es. Nevertheless, it is useful—even necessary, according to the Second Vatican Council’s Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, Dei Verbum—to look into the literary forms of the inspired text, by which the intention of the sacred writers may more readily be ascertained. In other words, the literal sense of Scripture, which grounds the spiritual senses, is bound up with the literary nature of the text, and therefore the literary nature of the text demands attention.

This requires some thought about the Bible’s human authors, who were at least partly responsible for its literary and artistic qualities. These chosen, inspired instruments were not mindless funnels or robotic conduits for the overpowering violent force of God’s authorship of Scripture. Rather, they “made full use of their powers and faculties so that, though [God] acted in them and by them, it was as true authors that they consigned to writing whatever he wanted written, and no more” (Dei Verbum 11). Their faculties of intellect and will—and therefore their virtues—were fully engaged when, under the grace of inspiration, they wrote the sacred books.

Incidentally, for Flannery O’Connor, this full engagement is a sine qua non for any good literature, which requires the author to “operate at the maximum of his intelligence and his talents.” The fact of Scripture’s divine inspiration does not exempt it from this reasonable rule of art, and considered simply on the level of literature, the Bible is eminently artistic. But the only way to begin to understand great art is to experience it: one must hear Bach or see a Fra Angelico. So, too, for the story of salvation set forth in the Bible: the only way to grasp its art and beauty is to hear it, to read it. “A story,” O’Connor once said, “is a way to say something that can’t be said any other way, and it takes every word in the story to say what the meaning is. You tell a story because a statement would be inadequate. When anybody asks what a story is about, the only proper thing is to tell him to read the story.” Tolle lege, tolle lege, St. Augustine heard the child sing: “Take up and read, take up and read.”

Upon taking up and reading, we discover that the biblical authors were masterful storytellers. Of course, this great artistry we behold in the Bible does not prove that the human authors wrote as true authors. Had God only dictated the exact words to them—instead of more generally inspiring them—He could well have dictated very artistic words. But God allowed for the full use of their faculties, which means that the human authors, especially of the most beautiful parts of the sacred text, could be—and indeed were—both authors and artists.

Reflection of Eternal Light

Well and good, we might say. But the Bible is divine, too. Affirming its artistic excellence is like observing that Jesus was an outstandingly decent and honorable gentleman, which, to say the least, misses the point. Which brings me to my point: the Bible’s astonishing artistry, like its authorship, is not primarily human but divine. This is not to say that God is the giver of all good gifts and therefore the human authors produced a work of art only because God gave them the talent to do so. This is true, so far as it goes—but it does not go very far. The art of the Bible is not simply a matter of language, narrative structure, imagery, and all the things that normally make for good literature; it is a matter of God revealing Himself: “the eternal Word became one of us. The divine Word is truly expressed in human words” (Verbum Domini 11).

The artistry of the Bible is thus tied to the Incarnation: just as the eternal Word of God, “the reflection of eternal light” (Wis 7:26) who “was in the beginning with God” (Jn 1:2), united himself to our frail human nature, so this very Word of God is expressed in our feeble human words. As St. John Paul II told artists, “In becoming man, the Son of God has introduced into human history all the evangelical wealth of the true and the good, and with this He has also unveiled a new dimension of beauty, of which the Gospel message is filled to the brim. . . . [O]n countless occasions the biblical word has become image, music and poetry, evoking the mystery of ‘the Word made flesh’ in the language of art” (“Letter to Artists” 5).

What all of this shows us is that artistic inspiration and biblical inspiration are related, and the contact is deep. It is not for no reason, I think, that God chose to reveal Himself in such an artistically beautiful way as we find in Scripture, through the artistic gifts of the inspired authors. John Paul II shows this when he says:

Every genuine inspiration . . . contains some tremor of that “breath” with which the Creator Spirit suffused the work of creation from the very beginning. Overseeing the mysterious laws governing the universe, the divine breath of the Creator Spirit reaches out to human genius and stirs its creative power. He touches it with a kind of inner illumination which brings together the sense of the good and the beautiful, and He awakens energies of mind and heart which enable it to conceive an idea and give it form in a work of art. It is right then to speak, even if only analogically, of “moments of grace,” because the human being is able to experience in some way the Absolute who is utterly beyond. (“Letter to Artists” 15)

The inner illumination and experience of the Absolute of which he speaks here are characteristics of both artistic inspiration and biblical inspiration. “Inspiration” does not mean exactly the same thing in both cases, of course, but John Paul II shows that the disjunction is perhaps not so disjointed after all.

Art has to do with the goodness of the thing made—this holds for what God makes, too. In creating the world and us, God is artistic: “And God saw everything that he had made, and behold, it was very good” (Gen 1:31). In redeeming us after we turned away from Him, God is artistic: “O sing a new song to the Lord, / for he has worked wonders. / His right hand and his holy arm / have brought salvation” (Ps 98:1). In sanctifying us and renewing us in holiness, God is artistic: “A new heart I will give you, and a new spirit I will put within you; and I will take out of your flesh the heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh. And I will put my spirit within you . . . and you shall be my people, and I will be your God” (Ezek 36:26–28).

God’s artistry is seen also in this unique quality of Scripture: it is a living word. God has spoken to men through it for centuries and continues to do so today. By immersing ourselves in the word of God, we draw near to the mystery of God’s nearness and transcendence, to His inestimable wisdom and love: “Come to me, you who desire me,” says Wisdom, “and eat your fill of my produce. / For the remembrance of me is sweeter than honey, / and my inheritance sweeter than the honeycomb. / Those who eat me will hunger for more, / and those who drink me will thirst for more” (Sir 24:19–21). The biblical authors were taken up into God’s plan of self-revelation. We who are the recipients of this revelation are thereby instructed and illuminated even today with a wisdom which is sweeter than honey. Of all literature, only with Scripture can we be thus illuminated. Only with Scripture is it possible for us to say, together with the Church at prayer, “When we listen to your word, our minds are filled with light.”

To download a printable PDF of this Article from

Dominicana Journal, Winter 2015, Vol LVIII, No. 2, CLICK HERE.

Endnotes

* All quotes from Flannery O’Connor are taken from the following two sources: various articles and lecture notes collected in Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose and letters collected in The Habit of Being.