The first Christian heresies were remarkably weird. Many fell under the umbrella of Gnosticism, which claimed that Jesus and the apostles had teachings that they kept secret from the masses. In their view, only the leaders of the gnostic sect knew the whole truth, and the Church erred about the fundamentals of theology.

Gnostic secret teaching posited the existence of a spirit-world called the Pleroma. According to a major strain of Gnostic cosmology, the perfect, pre-existent Bythus is the origin of 29 other spiritual beings known as Aeons who dwell in the Pleroma. The Aeons are divided into the Ogdoad, the first eight, the Decad, the middle ten, and the Duodecad, the final twelve. Many have names significant to Judaism and Christianity, like Church, Faith, Word, and Paraclete. Sophia, the last Aeon, once felt a passion to know the unknowable Bythus, and the failure of this audacious act led her to great agony. From her grief she produced a new, material substance, the Demiurge. The Demiurge proceeded to create the evil material world. After Sophia repented from her evil, the Aeons produced the precious Savior Jesus. With Sophia, Jesus gave humans a spiritual aspect. Humans are perfected when their spirits cast off their animal nature to enter the Pleroma and marry angels.

If this strikes you as an absurd word soup that bears little resemblance to Christianity, you’re onto something. Gnostic cosmology is contrary to revelation. For starters, “God saw everything that he had made, and behold, it was very good” (Gen 1:31). God is one, he created the material world as good, and the Bible has no reference to Aeons. Gnosticism clearly has little to do with the Bible. Nonetheless, the Gnostics claimed that the Bible teaches Gnosticism to lure Christians into their false teaching.

Saint Irenaeus, a 2nd century Church father who refuted the Gnostics, mentions their excuse for why the New Testament does not openly teach gnostic doctrine. They “impudently assert that the apostles, when preaching to the Jews, could not announce to them any other God than the one in whom they [already] believed.” The apostles, they claim, were limited by the intellectual culture of their own time. Thus, while they had a fuller knowledge, they could not preach the truth. We hear echoes of this today. Many people claim that Jesus and the apostles were limited by their society and thus could not openly contradict Jewish notions of priesthood or of marriage. The argument fails for the same reason that reconciling scripture with Aeons fails. Such a view eliminates the coherence of revelation and the possibility that anyone could know the truth about God. St. Irenaeus responds:

“According to this manner of speaking, no one would have the rule of truth, since all the disciples would credit their [teachers] with giving out speech according to the capacity of the one to understand and grasp it. Moreover, the Lord’s coming would appear superfluous and useless if He came to permit and preserve the notion of God that each one formerly had implanted. Furthermore, it would have been more difficult to preach Him as Christ the Son of God, their eternal King, whom the Jews saw as a man and whom they fastened to the cross. And so they did not speak to them according to their former notion” [Against Heresies, book 4, chapter 27].

St. Irenaeus shows us that the apostles taught us faithfully. Jesus taught a new, fuller truth, and he did not fear contradicting the common culture. He handed down his teaching to the apostles, and this tradition is a great gift: it teaches us the truth about God. It is illogical to hold that Christians can believe anything that contradicts the apostolic teaching. Whether the novelty is from 150 or 2020, to deviate from apostolic teaching is to deviate from Jesus’s teaching and deny that he can truly guide us. Rather, “we possess the prophetic message that is altogether reliable” (2 Pet 1:19). We may take confidence in this teaching, the truth is not far from us, should we only choose to study it.

✠

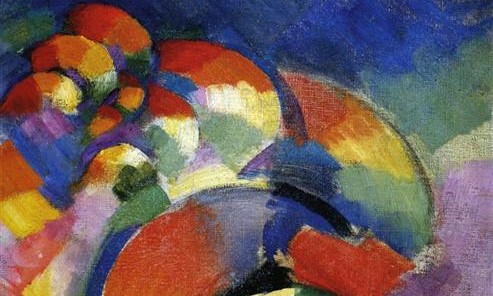

Image: Morgan Russell, Cosmic Synchromy