On hearing the word “asceticism,” a number of associations rush to mind. Most typically, we recall the standard fare of Lenten practices—fasting, abstinence, perhaps the sacrifice of some beloved comfort. For the most part, we tend to associate asceticism with foregoing some secondary good, be it satiety at the end of a meal, red meat, or warm showers. While this is the beginning of a healthy understanding of penance, it does not entirely capture its spirit. It is not too difficult to see how the disposition in which these practices are conducted could be self-centered: Lent approaches. I brainstorm things to do that are difficult. I do them for Jesus. Easter rolls around, and I revert to past practices. While perhaps it is implicit, the central reality of conversion falls to the periphery in this approach to asceticism. Rather, what assumes an exalted status is the disciplined flexing of one’s penitential muscles.

At the heart of the traditional sense of asceticism is the understanding of training, a fact revealed by the etymology of the word itself (from the Greek askēsis, which means training or exercise). Now, given that training is ordered to an end, it seems natural to ask, “Training to or for what?” Simply put, the answer is union with Christ. At the root of asceticism we find the parallel scriptural affirmations: On the one hand, “All creatures are good,” and on the other hand, “God has highly exalted [Christ] and bestowed on him the name which is above every other name.”

So, while one must affirm the goodness of the created order—of food, drink, etc.—one must simultaneously recognize that these goods are not all of equal importance. That it is more important to save a drowning child at the community pool than to keep one’s swimsuit dry for the drive home so as not to ruin the interior is immediately evident. And yet, while this example is a no-brainer, it is evident from our experience that the choice between goods of unequal value can at times be excruciating. The battle with the snooze button every morning is a testament to this dynamic.

In addition to the importance of recognizing a hierarchy of goods, the character of asceticism also draws its urgency from the fact that we worship an invisible God. Consequently, it can be a struggle to choose Him consistently when we are presented with more immediate, more sensate, and seemingly more alluring goods. Our vulnerability to the seductive power of lower goods arises from the fact that God, though truly incarnate, remains hidden: the height of our knowing Him in this life is as unknown, in the words of Pseudo-Dionysius.

With the reasoning thus laid out, it may be clearer why there is a need for asceticism in the Christian life. By the grace of God and the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, we must be trained to choose God—the highest good—consistently, promptly, and easily, and from this choice to affirm all other goods in their place. Given our fallen nature and the consequent concupiscent slump towards that which can be more easily touched, tasted, compassed, and consumed, the believer must conduct a campaign—at times violently—to seek the things which are above so as to attain to true happiness. For only in this pursuit are the very delights attendant upon secondary goods preserved. The proposal is arduous but, as the lives of the saints so eloquently testify, it is possible.

✠

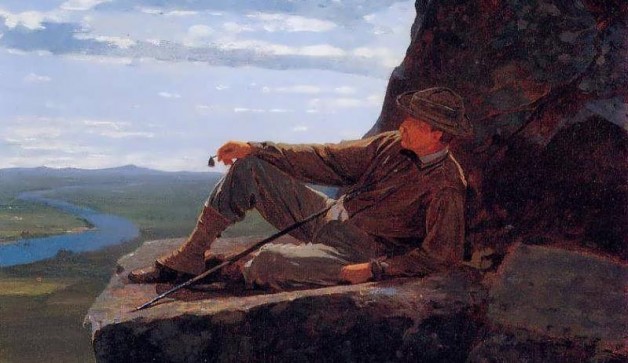

Image: Mountain Climber Resting, Winslow Homer