Editor’s note: This is the third post in our newest series, Beholding True Beauty, which consists of prayerful reflections on works of sacred art. The series will run on Tuesdays and Thursdays throughout the month of October. Read the whole series here.

How close can a work of art get us to God?

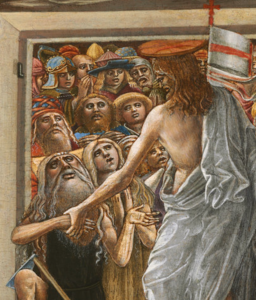

In the case of Benvenuto di Giovanni’s Christ in Limbo, the answer is pressingly close.

The central drama of this medieval depiction of Christ’s descent to the dead involves two antithetical forms of closeness: one being the undesired, uncomfortable congestion of the souls in Sheol, and the other being the long-desired, liberating intimacy that the Savior brings them. Giovanni thus portrays Christ’s victory over Satan as the victory of authentic closeness: the closeness that only union with God can supply.

It is the unique depiction of the souls of the just—absolutely crammed into this cave-like underworld—which first catches the eye. Rows and rows of Old Testament figures, including Adam, Eve, and King David, are heaped on top of each other, without an inch to spare. Examining their confinement, a kind of spiritual claustrophobia starts to set in.

At the same time, one gets the impression that if just one can be pried free, they will all come pouring out. And this is precisely the redemptive chain-reaction that Christ has come to effect. He stretches his arms across the length of the door frame, securing Adam and one of the patriarchs in his hands; they reach out to him in return, laying hold of the Source of their glory. Christ’s eyes, fixed on Adam, bespeak words attributed to Him in an ancient homily for Holy Saturday—words that convey the divine intimacy for which mankind was made: “Arise, O man, work of my hands, arise, you were fashioned in my image. Rise, let us go hence; for you in me and I in you, together we are one undivided person.”

To gain this intimacy, Christ has broken down the doors of the underworld. They didn’t just fall off; they were torn off their hinges and thrown down. The doors, toppled over, lay beneath Christ’s feet. He stands on that which was designed to create a barrier between these souls and Himself. Now the Savior uses them for a different purpose: to pin down Satan. Indeed, the only figure who is isolated from others in Giovanni’s work is the devil. Lying alone, his legs trapped, he appears totally and utterly defeated—no more than a part of the landscape (Giovanni, known for experimenting with spatial distortion in his works, has Satan appearing totally flat and two-dimensional). He is not getting up anytime soon. He poses no threat. Satan stares up at his former stronghold, raided before his very eyes. Now he is the one imprisoned in his own house, helpless against Christ’s plundering (Mt 12:29). Christ first vanquished him on the Cross, and now has taken the battle to the devil’s home turf. The victory is thus a total one.

Christ in Limbo makes up one panel of a predella (smaller paintings appearing beneath a larger altarpiece) on display at the National Gallery of Art. Of the five scenes, this one draws you closest. I recently spent a morning admiring the work, and after some time I found that other visitors followed a consistent pattern: those who walked into the gallery would stop, survey all five works, and then choose to step toward Christ in Limbo to get a closer look. One young man got so close that the security guard exclaimed, “You’ve got to stay twelve inches away!” Turning to me later she remarked, “He’s got his hair on the painting. Who does that?!” Someone who is being drawn closer, that’s who.

✠

Image: Benvenuto di Giovanni, Christ in Limbo