When observing beautiful art or music, how do we feel? Comfort, joy, and even euphoria come to us. We are drawn in by the otherworldly-ness of it all.

But what about stark or disturbing art? A Flannery O’Connor character’s gory end shocks us. The tragic eyes of Francisco Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son unsettle us. The harrowing loneliness of Blind Willie Johnson’s blues song “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” depresses us. These do not leave us in “awe” the same way as beautiful pieces. The technical skill may be just as laudatory, but the art itself invokes silence in us. We are haunted by them.

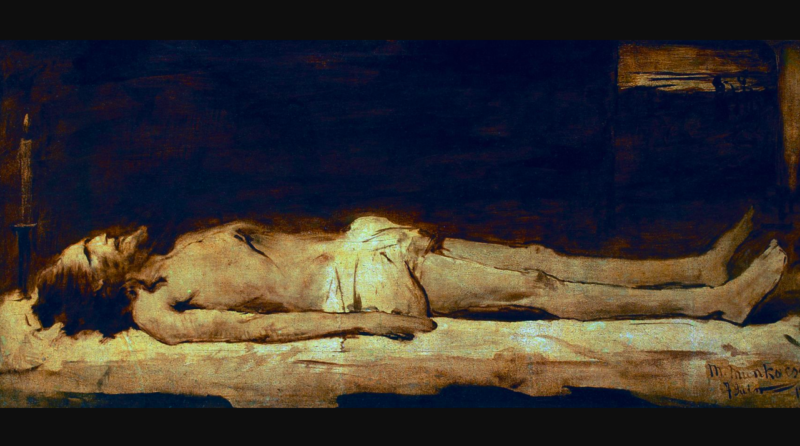

Disturbing art strikes a dissonant and palpable chord because it forces us into a “dark night.” This art draws attention to our memories and experiences of anxiety, despair, anguish, and darkness, reminding us of a vulnerability in us we would rather forget. These feelings ultimately signal our helplessness in the face of death. We all will one day sit in that dark night of our mortality, lying on the cold ground.

From our limited scope, nothing can drive out this night. In Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, the cold atheist Ivan uses stories of the disgusting abuse of children as examples of the senselessness of this life’s darkness. “And if the suffering of children goes to make up the suffering needed to buy truth, then I assert beforehand that the whole of truth is not worth such a price.” When we dwell alone in this dark night, Ivan seems to be right.

How absurd it seems, then, that we find the dispeller of this night in its darkest hour.

Human suffering does not alone unite O’Connor, Goya, Johnson, and Dostoevsky. The crucifixion and death of Jesus Christ is the fundamental principle underlying their work. For O’Connor, Johnson, and Dostoevsky, this is explicit through their Christian faith. But even Goya, who distanced himself from the Church, implicitly cries out to the Cross from the darkness of his work.

Because the most stark and disturbing truth is that God died.

On that dark night, anxiety brought God to sweat blood.

God was betrayed, whipped, beaten, embarrassed.

Nails plunged through God’s hands and feet.

God hung dead from a cross.

God was buried.

Lest it be believed that Christ died to end our earthly suffering, his own suffering is stark and brutal. Rather than giving us a platitude of endurance, God sends himself to die. God condescends down into our darkest nights, into our most uncomfortable memories, into the horror of our sin, into the misery that makes us cry “My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?” (Ps 22; Matt 27:46).

So we sit with him in the strange silence of the dark night. Until the silence of the empty tomb should confirm the glory that awaits.

✠

Image: Mihály Munkácsy, Krisztus a sziklasirban