Then Jesus was led up by the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil.

—Matthew 4:1

“Wilderness” is a shifting term. The Greek term that Saint Matthew uses in this passage, erēmos, means a desolate and lonely place, a “desert” in the literal sense of a place that has been deserted by all. In keeping with our knowledge of first-century Palestine and its environs, we generally imagine Christ’s forty-day fast occurring in an empty waste of sand and stone, where the scorching sun has scraped the open land free of any shade or respite from its heat.

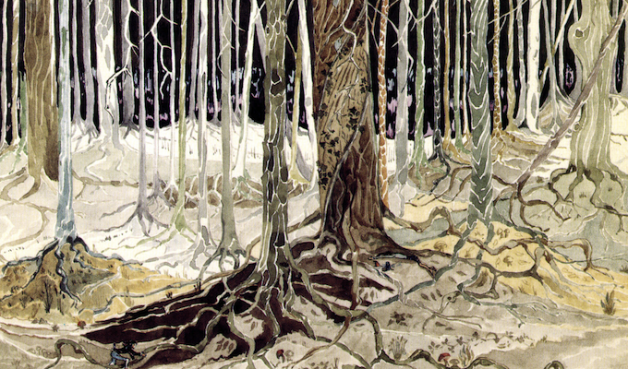

But not every culture has looked to Palestine as the first referent for Christ’s wilderness wanderings. The author of the Heliand, a ninth-century Saxon retelling of the Gospels, describes how “the good Chieftain Himself, the Son of the Ruler, after the immersion went out to the wild country. The Chieftain of earls was in the desert for a long time.” But the Saxon author does not have blazing hot sands in mind—after the temptations, Christ “left the protective cover of the woods, His desert dwelling, and made His way back to the company of earls, to the great crowds of people.” The Saxons imagined the desert of temptation according to their own notions of dereliction and waste: a deep, dark wood where no man would dare to tread.

The celestial poet Dante also understood the visceral terror and symbolic power of the close, impenetrable forests of Europe, employing them to create an allegorical narrative that ties the human experience of sin and brokenness to Christ’s wilderness temptations. The first canto of the Divine Comedy begins:

Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself in a dark wilderness,

for I had wandered from the straight and true.How hard a thing it is to tell about,

that wilderness so savage, dense, and harsh,

even to think of it renews my fear!It is so bitter, death is hardly more—

Dante here describes the first, feeble moments of awakening, when the sin-scarred soul suddenly realizes his desolation, finding himself in a forest of temptations, pain, and vices from which he cannot escape. The selva oscura that Anthony Esolen translates “dark wilderness” is often rendered “dark wood,” and we should keep both senses in mind when reading the passage.

Dante connects his narrator’s wooded wilderness with the desert wilderness of Christ’s temptation. Soon the narrator faces three beasts representing the three great temptations: the leopard of concupiscence, the lion of pride, and the wolf of avarice. These are the same three temptations with which Satan confronts Christ in the Gospel of Matthew, presented in the same order: turning stones into bread, exhibitionist wonder-working, and possessing all the kingdoms of the world. Christ’s ease in rebuffing Satan contrasts painfully with Dante’s narrator, who allows the temptations to force him back into the dark wood of sin from which he was looking to escape.

Dante overlays narratives of Christ’s strength and man’s weakness onto the same symbolic landscape, revealing both the intimate relationship Christ has with man through his human nature and the surpassing dignity he possesses through his divine nature. Christ, too, wandered in the dark woods of temptation for man’s sake, but unlike us he was neither oppressed by their darkness, nor led into sin.

Close, suffocating woods are a profound symbol for temptation and the life of sin in modern times. The spiritual deserts of our culture, the true places of desolation and abandonment, are not open, empty spaces, but crowded cities that batter their denizens with visual clutter, lash them with cloying, manipulative advertisements, and trip them up with the hidden roots and pits of lust, self-obsession, and greed. We find ourselves barren through over-stimulation and excess; loneliness consumes us even as we push through a crowd. Nor is this effect limited to physical cities; an all-encompassing consumer culture enables a man to be trapped in a forest of numbing over-stimulation even in a country homestead.

Through their meditations on the Gospel, the author of the Heliand and Dante have a profound answer to the frenetic bustle and claustrophobic closeness of modern society: the dark wood is not the final truth about mankind. Jesus Christ is the light that is “the light of men;” he is the light that “shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it” (Jn 1:4-5). He is the Master of the forest. He entered into the wooded wilderness of human life and so became a luminous beacon shining in our deepest darkness, brushing aside the branches and brambles with which we are surrounded.

In his forty days of wilderness wandering, Christ drew to himself the whole history of human sin, bearing it with him on his three-year journey to the Cross. This Lent, as we recall his act of love by our small sacrifices of love, we cry thirstily to God from the dark woods of our lives, looking expectantly to the coming of him who “turns wilderness to pools of water, and parched land to springs of water” (Ps 107:35).

✠

Image: J.R.R. Tolkien, Fangorn