It was a perfect plan. The lady was old, and she never really had visitors. Every Halloween, she would spend all day making fresh caramel apples to hand out instead of the usual little candies. It was the mother-load, and this year the boy was going to cash in. The old woman was lonely—he’d heard his mom say so—and with kids knocking at her door all night, she’d be too excited to notice that it was the same one, over and over again.

The plan’s execution was flawless. A set of nondescript black sheets and a bag of thirty different ghoulish masks was all it took. He rang the doorbell, collected his sugary spoils, switched masks behind the house, and then did the whole thing over again. Other kids would come by too, but that was fine—it kept her from getting suspicious. Plus, it gave him time to wolf down his winnings. By night’s end, he had cleaned her out. And he never got caught. He just walked away, a little sick to his stomach.

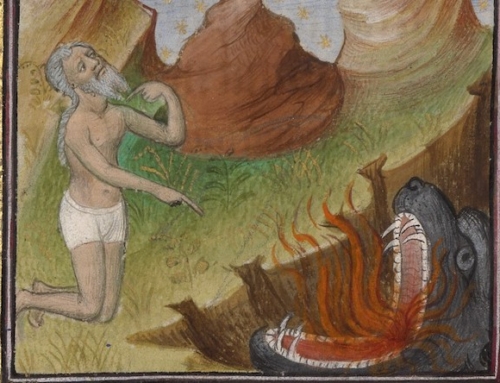

There’s something about sin that hates getting dragged into the light. Wickedness seems to drop into the darkness with all the force of gravity. When we do wrong, we hate exposure. Perhaps this is why we’re so tempted to put on masks. And perhaps it’s why we often make them ugly.

On the one hand, a mask grants us anonymity. Like a portable hiding-place, it serves as a social buffer, distancing us from our actions. “It wasn’t me who stole the caramel apples,” we might say, “it was that boy with all the masks.” When we’re wearing a mask, we can disassociate ourselves from our despicable deeds.

But on the other hand, the very existence of the mask proves that—on a more profound level—we know exactly what’s going on, even if no one else figures it out. We recognize that there’s something ugly within us, and we try to remove ourselves from it by putting on a mask. But we know the truth. At the end of the day, the real ugliness isn’t in the mask, it’s in us. Putting on a monstrous mask doesn’t remove the monster within, it just diverts attention.

When St. Paul commands us to “put on the Lord Jesus Christ” (Rom 13:14), he is not telling us to put on a mask. Life in Christ is not something external that we apply in order to distance ourselves from the wicked person we really think ourselves to be. Being Christian is not hiding behind the goodness of Christ and hoping that the Father doesn’t figure out what we’re up to. Old ladies might fall for it, but last time I picked up Genesis, God knew when we stole his apple.

Putting on Christ means letting him transform us from within. There is no deception here, no distance between what the world sees and what we know ourselves to be. Jesus came, not merely to make us look like him, but to actually make us one with him.

The Christian life, then, isn’t the strapping on of external righteousness; it’s the stripping away of internal sinfulness. Sin is like a mask on our soul, making us appear to be what—at the very core of our being—we are not. For beneath the disfiguring mask of sin lies the image of God.

Christ alone has the power to strip away our wickedness. Christ alone has the power to remove our inner disfigurement. Christ alone has the power to draw us up into his own wonderful light, in the radiance of which we will be able to look on him face to face.

As we prepare to celebrate All Saints and All Souls, we can beg the Lord Jesus to send us his Spirit, cast out the darkness within us, and let the light of his face shine upon ours. There in heaven, freed from the constraints of every mask, we will rejoice forever in the eternal feast of heaven—a feast that will never leave us feeling sick.

✠

Image: Gaetano Chierici, The Mask