If you are a fan of “Star Trek: the Next Generation,” you may have seen a terrific if cerebral episode entitled “Darmok.” Captain Picard is stranded on a lonely planet with a ship’s captain of an alien race he has never encountered before, and his trusty Universal Translator device doesn’t seem to be working; or rather, it does its job, but he still has no clue what his counterpart is talking about. He hears everything the alien captain says translated into English, but every utterance is something puzzling like “Darmok and Jalad at Tenagra. Temba, when the walls fell!” Eventually Picard realizes that his counterpart is speaking entirely in references to his culture, so even with a perfect translation of the words he still can’t understand the meaning until he learns more about Darmok, Jalad, Tenagra, and the rest.

We have studied at some length how to interpret the prophecies of the Old Testament. But if we just plunge into the book without learning the “vocabulary” of its images, we will be in much the same situation as Captain Picard—understanding all the words but few of the meanings.

Fortunately, we don’t have to challenge savage alien wildlife to a knife fight like Capt. Picard in order to learn the “vocabulary” of the Book of Revelation. The “word bank” St. John’s visions draw upon is our spiritual heritage: the Old Testament. Even those of us who can’t quite remember how many Books of Kings there are or whether Shealtiel is a good guy or a bad guy may find that we know more of the references than we expect.

But first, let’s see why it makes so much sense that God would give St. John visions that use the Old Testament in this way. We can understand it in terms of what we have learned about prophetic visions in the previous posts: that they require interpretation, that they conceal from some while revealing to others, and that they have manifold meanings and fulfillments.

1. Requires Interpretation.

The way God speaks to us in the Bible is not typical of bureaucratic regulations or even scientific treatises. It is personal self-revelation, as one friend communicating to another. Time spent in conversation with a beloved friend isn’t a waste of time; no one worries about how to extract everything there is to know about a friend in the most economical fashion possible so as to drop him and get on to other things.

If that’s the case, why is God’s self-revelation often so derivative? Why does the Book of Revelation constantly refer to other things God inspired? Why doesn’t God just say something totally new?

One major reason is that truly great literature is always intertextual, always locating itself within a larger world of symbols, stories, and tropes in order to express the truth more beautifully and deeply. In a much simpler way this is true even in casual conversations with friends—much of the time what delights us about our friends’ comments is not their cultured brilliance and polish, but the references to a life lived in common, to joys and sorrows shared and enriched by recollection. To outsiders such conversation would probably be mundane at best, but to friends who understand all of the subtle allusions and references, it is a source of rejuvenation and communion. The allusiveness and intertextuality of the Scriptures captures this dynamic of human interaction and elevates it into literary art and spiritual mastery. This interpretative nature of the Book of Revelation also makes the next two points possible.

2. Conceals from some while revealing from others.

God’s self-revelation is for everyone insofar as his call is universal, but it is not for everyone in the same way. For instance, the book will always be opaque to those who refuse friendship with God, because it is written largely in references to a culture beloved by the people of God and boring to most others: the Sacred Scriptures.

In the time of St. John and the early Church to whom he wrote, there was a very practical pastoral dimension to the cultural opacity of the Book of Revelation, as it was best not to let the pagans who were persecuting Christians in on everything about their spiritual resistance to them. But that is not all there is to it. Who doesn’t love “getting” the cultural references in a book, TV show, or movie? It makes us feel included and privileged that we are in the know. How much more so when the book is God’s revelation? How much more so when these references give us access not to pop culture or even to literary culture, but to the very mysteries of God? The pagans who were persecuting the early Church generally didn’t care to devote the necessary study to the Old and New Testament to understand the references and thus the Book of Revelation. But Christians love the Scriptures for the sake of God, and not primarily as a tool to understand secret communications. So the Book of Revelation is to us not a tedious code but a privileged place of communion with the Lord.

3. Multiple layers of meaning.

The Book of Revelation is written so that it can say a lot with a little. It is only twenty-two short chapters long, yet since almost everything stands for many things, the symbols in its short span bear an amazing depth and multiplicity of meaning. Some of the fulfillments are known to everyone in the Church, some are yet to come, and some perhaps God reserves for those who are advanced in mystical union with him, as is true of the rest of the Scriptures.

Because of this, we don’t need to worry about getting to the end or exhausting the Book of Revelation. Like the rest of Scripture, it is a well that we can come to drink from again and again. Some people (especially those who try to ‘go it alone’ without the Church) seem to have a panicked approach to interpreting it. They seem to think that their salvation hangs on their ability to understand every single prophecy, or perhaps that they will be punished if they do not figure out all its secrets right now. On the contrary, the Catechism of the Catholic Church lays out the basic end-times beliefs needed for healthy Christian life (around paragraph 666—seriously), and most of us would probably be surprised at how little the Catechism has to say on the topic.

The Book of Revelation, like the rest of the Bible, is not a secret codebook by which God communicates winning plays to a privileged elite. It is God’s personal communication to his friends, intended to change our lives and bring us closer to him. To deepen and enrich our lives of faith, hope, and love, we will want to return to the Bible again and again to contemplate its mysteries.

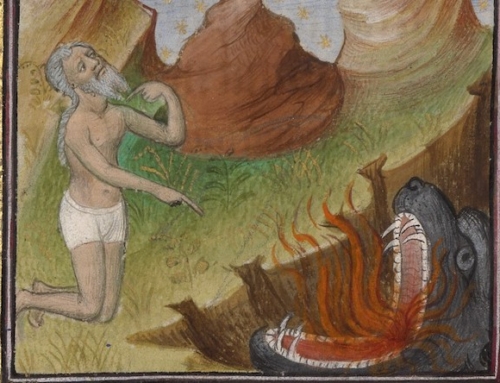

We will return to the Old Testament in the next few posts to prepare ourselves for our reading of Revelation. We will consider three important images from the Old Testament and what the sacred author tells us they symbolize: Beasts, the Mark on the Forehead, and Marital Fidelity. After a brief additional discussion of numbers and narrative conventions in the Old Testament, the final course of posts will begin: a tour of the Book of Revelation, applying what we know.

Image: Michelangelo, Last Judgment