It needed attention. Built in 1925, it was a neglected old cottage. The kitchen would require a good gutting and upgrade. The plumbing and electric were in a state of dangerous mutation. Having received only minor fixes and accretions over eighty years, these essential sources of domestic comfort were in a precarious place. We didn’t want galvanized pipes bursting into old knob & tube wiring, so we’d have to replace it all. The walls, ceilings, floors, and siding needed fresh paint jobs. And it smelled bad. Still, we–my parents, sister, and I–bought it. Beneath the shag rug (hardwood floors) and aluminum siding (original clapboard siding), we saw potential. It was worth conserving.

As this little tale of home improvement shows, the act of conserving involves much more than simply trying to keep things the same, and restoration more than seeking to return things to their previous condition. This job took lots of work and years to complete. And that was just to make it inhabitable. But if one wishes to keep something around and keep it beautiful, whether it be a house or anything else of value, one cannot leave it be. Time and weather will work their decay on it. Bad taste will too. I forgot to mention: some former owner had glued a gigantic mirror to a random wall. It covered the wall from floor to ceiling and wall to wall. Our house not being a dance studio, we dismantled the mirrored wall, carefully of course. The problem with time, weather, and bad taste here is that if they go on for too long, their object will fall into a state beyond repair. So to conserve something is to revisit it repeatedly in order to protect it from those forces working against it.

While discussing his idea of true conservatism, Chesterton writes, “If you leave a thing alone you leave it to a torrent of change. If you leave a white fence post alone it will soon be a black post. If you particularly want it to be white you must be always painting it again.”

If you would preserve something you must attend to it by returning to, checking in on, and updating it when necessary. This reveals the active, dynamic nature of conservation. But you only attend to something you value. We would not have worked on that house if we didn’t think it was worth it. So, besides old houses, what is worth conserving? Many things, but I want to focus on a “permanent thing” close to home, or rather, even closer than home: one’s soul. Our soul is living and permanent. It is also made for the life of grace. But like the house or Chesterton’s white fence post, it’s also open to its own “torrents.” So it’s important we attend to our own spiritual life, in order to protect our souls from whatever would harm them.

One reason we neglect our souls is that it’s difficult work. It takes time and effort to establish virtue. And the longer we neglect some area of our spiritual life, the more time and effort it takes to restore it. But there’s something deeper here needed for this spiritual project: the workings of grace. A clean soul is effected by the work of grace. But if it’s that simple, why do we resist grace? Flannery O’Connor put it well in one of her letters: grace hurts. It heals but it hurts. I think about all of that clapboard I scraped with my Dad before we painted. We scraped and sanded that siding so that it was ready for a new paint job. If the house could have said, “ouch,” it would have. But after all the prep work, the wood was ready to receive the new paint job. Like the sander to the plank, grace on the heart can be rough. Grace changes us. And change doesn’t happen overnight. It’s a long process, but it does have a beginning and end. Our beginning is our baptism and our end is, please God, God Himself. But we must let this work be done unto us. And when we do we’ll be conserving our life.

I’d like to end with an excerpt from a poem my father wrote on this subject of restoring homes and souls. It captures in a few lines what I’ve been trying to flesh out above. It’s appropriate, as the title suggests, and it reveals how the workings of grace in one’s life can also inspire one to respond to God’s call. And God willing, if my vocation is to the priesthood, it will involve a lifetime of cooperation in God’s act of restoration.

✠

Restorations

…after we achieved the restoration

From basement drain up through to shingled peak,

We left the house to follow our vocations:

I your father, you your own to seek.

And if yours leads you to the altar

And to the fields where laborers are few,

Where you will work restoring broken nature,

Understand the bonds are not to you,

But to the Master Builder, to the Carpenter,

Whose plumb lines drop like blades of light to earth,

To warm a way for lost and wicked wanderers –

As will you to prove that it is worth

The sweat, the gutting, and the leaving

Which restorations probably demand

And remember that with this pain of cleaving

You are mating up the unions God has planned.

-Brian P. Bolger

✠

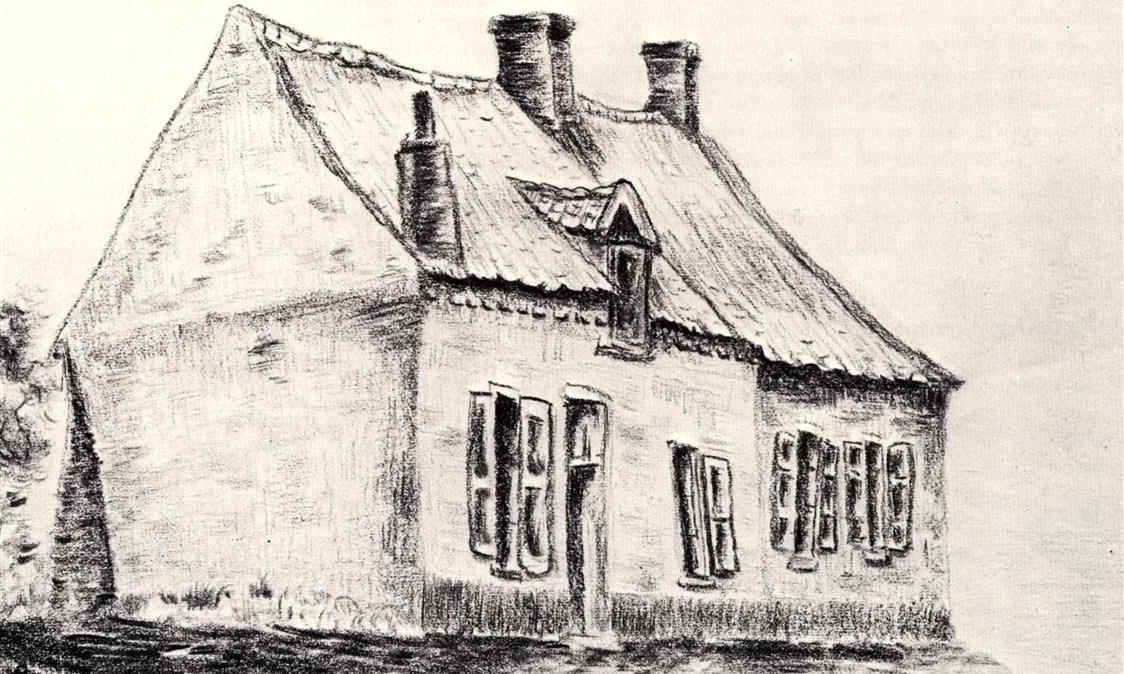

Image: Vincent van Gogh, A house Magros