On a good day, perhaps, we remember to “offer up” our sufferings. We might say, for example, “This conversation, which I know will be mildly unpleasant, at best, is for Uncle Jack who’s suffering from cancer.” Maybe we even make a morning offering of our whole day, giving all our sorrows and joys to the good God. Underneath these basic pious activities lies an impulse at once primal and Christian, ingrained in our nature and perfected by grace: the impulse to offer sacrifice to God. And, in its fullest expression this impulse compels us to recognize not only our activities but our very selves and the whole Church as a living sacrifice offered up for the glory of God.

It sounds a bit strange to say that we are an offering. In fact, it can sound down-right barbarian to describe a person as an offering—the mind turns to Aztec temples, stone knives, or perhaps Shirley Jackson’s chilling tale, “The Lottery.” We know that the sacrifice of children not only occurred in nations neighboring the ancient Israelites, but tempted the Israelites (Lev 20:1–5). Jackson’s story makes clear what the more ancient practices obscured in bloody theatrics—human sacrifice manifests a mindless, horrible superstition. Looking back, it baffles the mind how anyone could consider such actions. I imagine the revulsion we feel towards human sacrifice at least in part comes from centuries of Judeo-Christian cultural formation. It is good that our stomachs turn at the thought of it.

But our stomachs should not turn so much that we dismiss the very idea of sacrifice. Bloody forms of sacrifice, for example ancient Israelite sacrifices that involved killing animals, acknowledge that since life comes from God, God can make a total demand on life. The legitimate animal sacrifices of the Old Testament expressed in an external mode the interior acts of contrition, adoration, and prayer, which the Jewish people, led by their priests, offered to God. The key to the meaning of these rites lies in the intention behind the offering. As Fr. Romanus Cessario writes, “If indeed some internal action did not specify the act of sacrifice, every slaughterhouse would become a temple.”

Likewise, Christ’s single sacrifice on the cross expresses and reveals his perfect interior act of love—his perfect love for his Father, and his perfect love for us: “The way we came to know love was that he laid down his life for us” (1 John 3:16). Love motivates sacrifice and is expressed by it.

Love for us drove him to the cross. And in his love, he brought us with him. He offered himself intentionally for each and every one of us, to turn us to the good, to heal our wounds, and to offer atonement for our sins. Christ knew that he received his disciples, the Church, from the Father: “Father, they are your gift to me” (John 17:24). In reciprocation, he offered the Church back to his Father: “everything of mine is yours and everything of yours is mine” (John 17:10). And in his sacrifice, Christ included us in his offering of love to his Father.

What have we to do, then, but to join ourselves to this great act of love? St. Paul instructs us: “offer your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God, your spiritual worship” (Rom 12:1). Extrapolating upon this passage, St. Augustine writes, “This is the sacrifice of Christians: we, being many, are one body in Christ. And this also is the sacrifice which the Church continually celebrates in the sacrament of the altar, known to the faithful, in which she teaches that she herself is offered in the offering she makes to God” (City of God, X.6). The sacrifice that Christ made of himself to the Father on the cross includes an offering of all his members. In the Mass especially, Catholics “offer the Divine Victim to God, and offer themselves along with It” (LG 11).

“Offer it up”: this stock phrase of perennial Catholic wisdom includes within it the key to unity with Christ and the joy of God’s presence in our daily lives. While the tragedies of our lives often help to show God’s total claim on our attention, the cross of Christ reveals that this divine claim need not be feared for what it may take. Rather, in perceiving the love at the core of reality, we are moved to ask what we can give.

✠

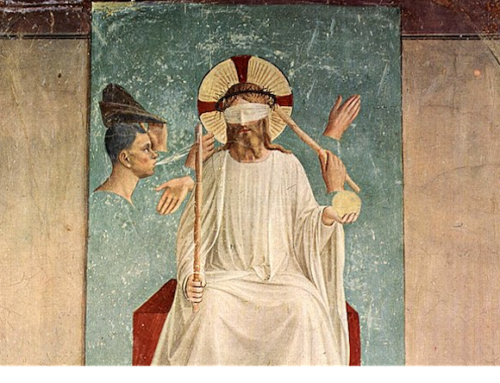

Image: Caravaggio, The Sacrifice of Isaac