Pope Saint John Paul II had a Dominican mind. This is not simply because he studied the writings of Saint Thomas Aquinas under the great Dominican master Father Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, or because he heavily invoked the Common Doctor in his two most important encyclicals, Veritatis Splendor and Fides et Ratio. Far more profoundly, the principal sign of John Paul II’s Dominican mind is that he recognized that all truly effective, truly pastoral preaching of the Gospel must be grounded in metaphysical realism—the perennial philosophical tradition that affirms reality’s basic intelligibility and man’s capacity to know it.

John Paul’s realist education began during his unconventional, clandestine seminary formation. Studying in covert classes by day, he would work night shifts at the Solvay chemical factory and peruse his metaphysics textbook during breaks. He would later reflect on that experience:

My literary training, centred round the humanities, had not prepared me at all for the scholastic theses and formulas with which the manual was filled. I had to cut a path through a thick undergrowth of concepts, analyses and axioms without even being able to identify the ground over which I was moving. After two months of hacking through this vegetation I came to a clearing, to the discovery of the deep reasons for what until then I had only lived and felt. When I passed the examination I told my examiner that in my view the new vision of the world which I had acquired in my struggle with that metaphysics manual was more valuable than the mark which I had obtained. I was not exaggerating. What intuition and sensibility had until then taught me about the world found solid confirmation. (Frossard, Be Not Afraid!, 17)

Most importantly, John Paul would note: “this discovery [of metaphysics], which has remained the basis of my intellectual structure, is also at the root of my essentially pastoral vocation” (Frossard, 17). Saint John Paul’s entire priestly life, from his early days as a professor in Lublin to his tenure as archbishop of Krakow to his nearly twenty-seven year pontificate, flowed from his keen grasp of the essential unity of truth—that the speculative and the practical, the intellectual and the pastoral, are ultimately inextricable. Truth without love is repulsive; love without truth is a lie.

Such pastoral concern was the impetus for John Paul’s foray during his doctoral and professorial years into modern, experientially focused philosophical traditions, particularly phenomenology. He wanted to understand man’s experience so he could speak Christ to it. Still, while never neglecting the experiential, John Paul always affirmed the more primordial reality of metaphysics, that science of being which grounds the Christian message in the real. This is perhaps best evinced in his final memoirs, when John Paul spoke with clarity and precision on that most intellectually and pastorally agonizing problem of evil:

If we wish to speak rationally about good and evil, we have to return to Saint Thomas Aquinas, that is, to the philosophy of being. With the phenomenological method, for example, we can study experiences of morality, religion or simply what it is to be human, and draw from them a significant enrichment of our knowledge. Yet we must not forget that all these analyses implicitly presuppose the reality of the Absolute Being and also the reality of being human, that is, being a creature. If we do not set out from such ‘realist’ presuppositions, we end up in a vacuum. (Memory and Identity, 13)

Metaphysical realism elevated by faith enables the Christian to attain a wisdom that pierces through our complicated experience of sin and suffering in order to behold the saving power of God at work in all things. It was this realist Christian wisdom—even more than his great personal charisma and apostolic zeal—that so equipped John Paul both to warmly proclaim from the pulpit, “Do not be afraid! Open wide the doors to Christ,” and then to charitably specify in his magisterium what this opening-wide to Christ entails on the most contested moral questions of our age.

Pope Saint John Paul II was not a Dominican. But his enduring conviction that metaphysical realism is essential to the preaching of the Gospel places him squarely within the intellectual and spiritual tradition of the Dominican Order. Once asked about the most important word in the New Testament, John Paul immediately replied: “Truth.”

Only truth, in the end, is pastoral. Only truth saves.

✠

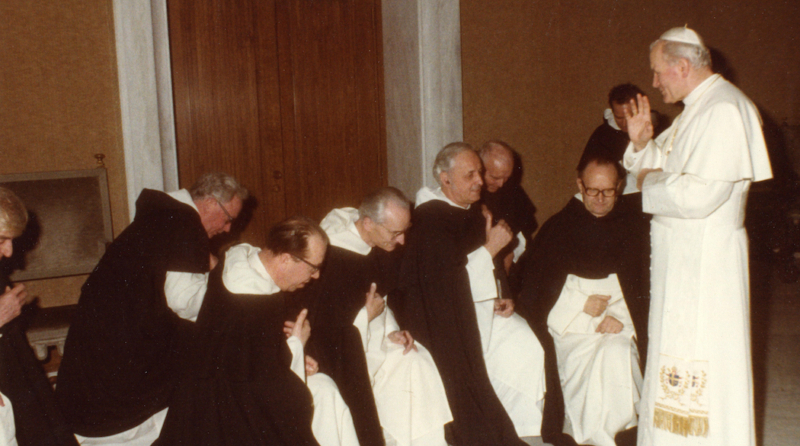

Photo by Dominican Friars Foundation (used with permission)