During my novitiate year, I visited residents in an assisted living facility every week. Sometimes the interactions were whimsical (once, a resident advised me on cheap places to take a girl on a first date—I don’t think he quite understood the meaning of the habit). But one particular resident left a lasting impression on me. Almost every week I’d stop by her room. Before long, she’d be relating memories of her school years, the nuns who taught her, the perplexing contours of her familial relationships. She’d reflect on the tapestry of her life, sorting out the different threads to see how they fit together. Sometimes she’d ask me for an explanation of some past tragedy—an explanation she knew I didn’t have. But the theme she returned to more than any other was her gratitude to God for the life he had given her and the many mercies he had shown her.

As the approaching end of life prompted this woman to reflect on her past and God’s mercy, so too does the approaching end of this Jubilee Year of Mercy prompt us to reflect on the events of this past year. This coming Sunday, at cathedrals around the world, bishops will close the Doors of Mercy that have been open since last Advent. And this Sunday, according to Misericordiae Vultus (the Pope’s letter that announced the year of mercy), “as we seal the Holy Door, we shall be filled, above all, with a sense of gratitude and thanksgiving to the Most Holy Trinity for having granted us an extraordinary time of grace.”

It might seem naive to describe this past year as an extraordinary time of grace. If we look back, we see acrimonious politics, precarious global relations, a violent Middle East, and catastrophic natural disasters. If we look forward, well, there doesn’t seem to be much to look forward to. Must we give thanks?

If thanksgiving after a year of global trials sounds insincere to our ears, thanksgiving after a lifetime of personal sufferings will sound flat-out facetious. And at first I did doubt the sincerity of my aging friend’s thanksgiving to God. I didn’t quite believe her, given that she was widowed, isolated, and spending most of her time in a small room in a nursing home, simply waiting—by her own admission—to die. But over time my incredulity receded in the face of her authenticity. She could clearly see truths I frequently forgot—that God “has mercy on those who fear him, in every generation” (Lk 1:50); that she herself was a particular object of God’s affection; that her life on earth was a gift to be pondered and the life to come a goal to be desired. Until her final day, aware of her many sins, she was going to make her own the psalmist’s prayer: “Have mercy on me, God, in your goodness; in your abundant compassion blot out my offense” (Ps 51).

The sense of gratitude Pope Francis asks of us at the conclusion of this Year of Mercy does not mean that we turn away from the darker threads of life. The Pope demands the opposite: “Let us open our eyes and see the misery of the world.” Our eyes, however, must also be “fixed on Jesus and his merciful gaze.” Through knowing the gaze of Jesus we can begin to look on the world and our own lives as he sees them—wracked with sin, groaning for redemption.

Though this Year of Mercy comes to a close, God’s mercy has no limit, no end. But in another sense, the end of God’s mercy—its purpose—is our redemption. And when God sent his Son as “mercy made flesh,” he revealed to us as never before that “mercy will always be greater than any sin, and no one can place limits on the love of God who is ever ready to forgive.”

✠

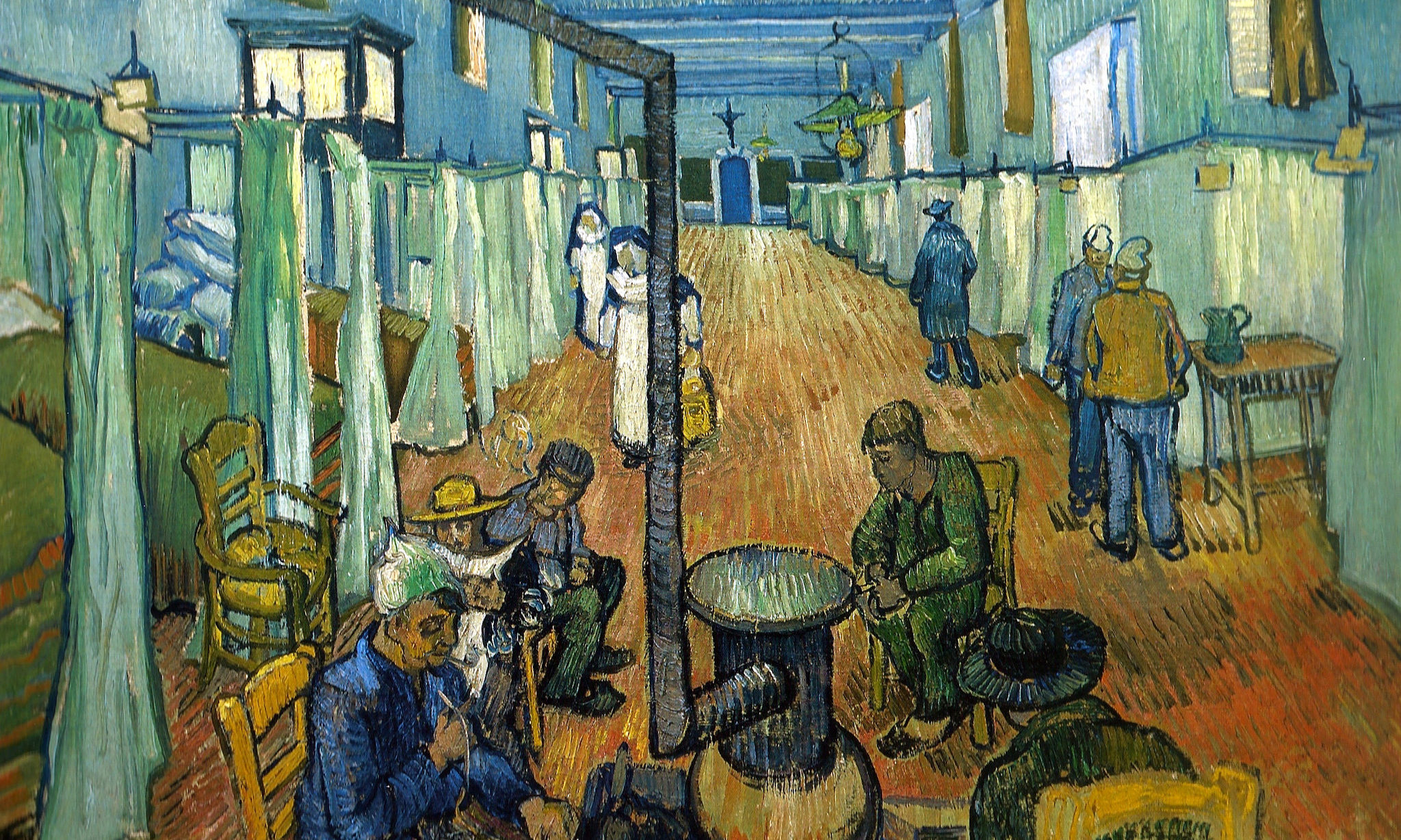

Image: Vincent van Gogh, Ward in the Hospital in Arles (detail)