One of the unexpected blessings of my parish ministry assignment this summer at St. Dominic’s in Youngstown, Ohio, are the regular funerals. There are funerals here at least once a week and each one is a reminder of how important they are for the spiritual lives of both the living and the dead. In the final lines of the Creed, we profess life everlasting; thus death only makes sense in light of Christ’s passion, death, and resurrection.

The practice of burying the dead is very old. By the time of the Greeks we see standards for honorable and dishonorable ways of handling the dead. Antigone dies trying to bury her brother even though he is considered a traitor and not worthy of a burial or even mourning. For Christians, burying the dead is one of the seven corporal works of mercy. Although it does not specifically appear with the other six in the Last Judgment Parable in Matthew 25, burying the dead is an important act of charity emphasized in the Book of Tobit. Tobit loses all his property and risks his own death by burying the dead against the wishes of the king.

I have often heard it said that one of the hardest parts of dealing with death comes after the burial when family and friends have left and “normal” life resumes without the loved one present. The funeral rites of the Church are designed to provide for comfort and healing as well as mourning for the entire community, not just close friends and family. The Order of Christian Funerals emphasizes that the entire community holds the primary role of providing consolation and support: especially by being present at the wake, the funeral Mass, and the burial.

The funeral is part of a continuum that begins by praying for and assisting those who are ill and dying. The sacrament of Anointing of the Sick assists the sick person with graces of strengthening, peace, and courage for the healing of the soul (and the body, if God so desires) so that the individual can be more closely united to Christ’s Passion and thus intercede for the Church. This sacrament and viaticum (the Eucharist received just before death: “food for the journey”) also provide special graces to overcome the final temptations and struggles before death.

After death, we pray for the dead and commend them to God’s mercy and care. The funeral Mass and rituals direct our attention to the continuity of life, while reflecting the changed nature of life after death. By means of the Eucharist, the funeral Mass focuses on the unity of all the faithful: those on earth and those in heaven. We can still pray and intercede for those who have died. On the other hand, the committal and burial emphasize the reality of separation while expressing the hope that we shall meet again. This is a process of letting go and giving to God, trusting in His great mercy and love.

Death is sorrowful, but it can also be an incredibly grace-filled time. Our funeral rites provide great consolation and express our Christian hope. Only together as a community can we really heal and let go, commending our loved ones to the mercy of God, with the great hope that we will all be together again.

May the souls of the faithful departed, through the mercy of God, rest in peace.

✠

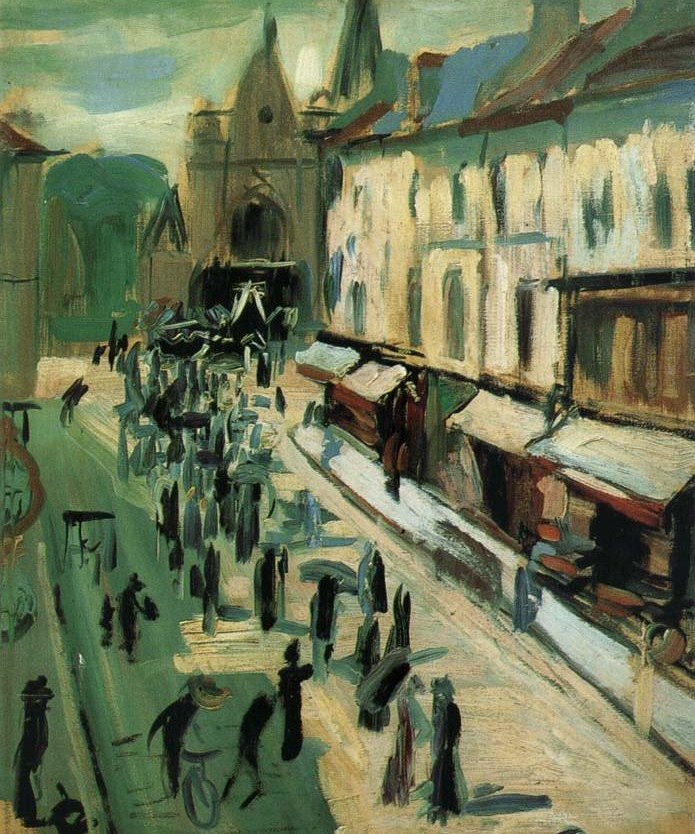

Image: Andre Derain, Funeral