The woman entered the temple to make her offering. Others in the temple were offering large sums of money, but she had only two small coins to give. Bystanders noticed how small her financial contribution was. Yet one of those bystanders commented to his friends, “This poor widow put in more than all the other contributors” (Mark 12:41-44).

The story of the widow’s mite can seem unrelatable to us. The widow lived in such poverty that her offering of two small coins was “all she had, her whole livelihood.” Yet despite her poverty, the widow was much richer than we are, because she was rich in virtue. The intrinsic difficulty of parting with all that she had seemed much more bearable because of her virtue. She was able to see that her small gift of two coins, though very dear to her personally, was a worthy act of worship to God. If we were in her shoes, would our wealth of virtue be able to overcome the difficulties that poverty or other challenging circumstances might bring?

As it turns out, then, we do have a poverty similar to the widow’s. Our poverty, though, is a poverty of virtue. When that one student is constantly disrupting class, is there anything left in our storehouse of patience? When YouTube offers to play another video in seven seconds, where’s our treasury of temperance? When a difficult situation arises in the family, how much prudence do we have to help us make the right decision? A virtuous response can feel like a heavy load when it comes time to reach into our wallet of virtue. We might find this wallet nearly empty, and, rather than arduously facing the vice with such few resources, it’s much easier to just give in.

Yet we’re told that we need to grow in virtue. We see the importance of these exhortations when we realize how virtue works in our lives. Virtue perfects us as rational creatures. Fortitude, for example, lets us act reasonably in the face of extreme danger, even though our animal instincts would rather shy away from reasonable conduct. Virtue, then, brings us to the fullness of our natural life by allowing us to live life according to reason. But then grace lifts this virtuous rational nature to live an even higher life: the Christian life, the life according to Christ. Virtue remains part of the natural groundwork that grace works within, bringing us to life with Christ. In this light, we see why Saint Peter urges, “Make every effort to supplement your faith with virtue” (2 Pet 1:5).

The point of virtue isn’t simply to teach us how to grin and bear it. Virtue perfects our nature, and in doing so, it’s supposed to give us joy. Aristotle realized this over two millennia ago when he observed that temperate people actually find joy in the temperate acts they carry out. He also saw that intemperate people find temperate behavior oppressive and difficult (Eth. Nic. 1104b). Acting with prudence or justice or temperance or fortitude is hard precisely because we’re deficient in these virtues. It’s simply difficult for us to become virtuous, since the school of virtue is often long and arduous. But we’ll find that the virtuous life does orient us towards reason, perfect us on the natural level, and bear fruit in joy.

The widow was poor when it came to financial resources, and this deficiency made giving all the more difficult. For our part, we’re often poor when it comes to virtue, and this deficiency can make living the Christian life all the more difficult. But we learn that the widow’s gift to the Lord, a gift difficult to make because of her poverty, was a gift precious in his eyes. We, too, can make a gift of our struggle to grow in virtue, especially when growth in virtue seems most difficult and insignificant. As we strive, then, to live the Christian life with virtue, let us offer our efforts to the Lord, asking that our offering be accepted as a sacrifice of all that we have, our whole livelihood.

✠

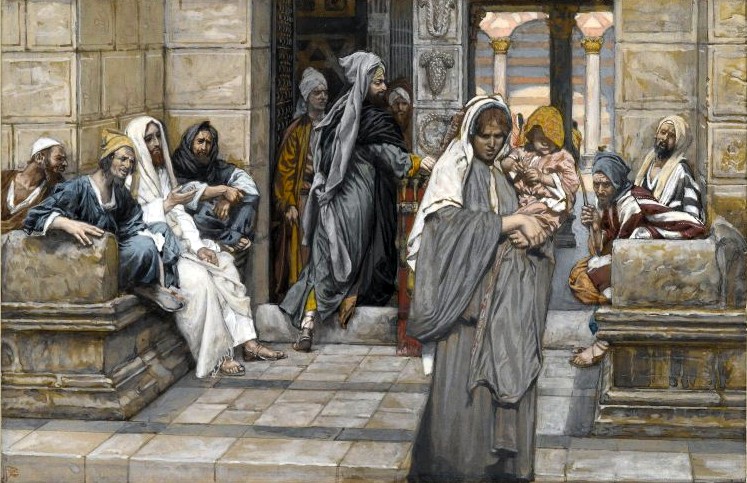

Image: James Tissot, Le Denier de la Veuve