A friend from another country once came up to me and ceremoniously handed me a folded-up piece of paper. Bemused and somewhat trepidatious, I opened it to find a five-verse hymn that he had translated from his native language, which began:

Welcome nutrition in which immeasurable

Maker of heaven and earth is enclosed/confined

Welcome beverage totally adipsous

mind panting after

Well, I thought, so this is what it feels like to be nonplussed.

I hope I never forget the feeling of looking at my friend’s eager face—“Isn’t it beautiful?” he was asking—and my own total incomprehension of what I was holding. From his excited seriousness I could tell that I was supposed to be deeply moved by the words on the page, but all I could see was the world’s strangest piece of refrigerator-magnet poetry. I guess it’s true what they say: one man’s trash is another man’s welcome nutrition.

Looking back on the verse later, I realized that this was nothing less than a hymn about the Eucharist. “Welcome nutrition” was surely some sort of reference to the life-giving food of the Lord’s Body, in which Christ himself is “enclosed/confined.” “Welcome beverage” must be a reference to the Precious Blood—an insight I later confirmed by discovering via the Oxford English Dictionary that “adipsous” is in fact an obsolete medical term meaning “thirst-quenching.” And, sure, the mind could pant after a totally adipsous beverage, if that beverage is the Blood of the God-man.

Now translation is hard in the best of circumstances, and translating poetry is even harder, so I don’t just want to make fun of my friend’s valiant effort to hand on to me a hymn that he found moving. The reason “Welcome Nutrition” stands out in my mind—beyond the sheer delightfulness of the phrase—is that this little encounter between my friend and me is a distressingly apt image of the way many of our contemporaries hear the Word of God when it is preached to them.

Even in our more or less secular age, Americans can’t avoid hearing people talk about God every now and then. Street corner preachers talk about judgment, billboards inform passers-by that Jesus loves them, televangelists and late-night radiomen work out their salvation in fear and tax-deductible donations, and earnest co-workers talk about the power of prayer. The problem is that the audience sees enthusiasm and hears gibberish. All this God stuff is obviously something very important to the speaker, but to the listener it’s just, well, unwelcome nutrition.

So how, then, are we to speak to our brothers and sisters about God, we who have fallen in love with God and come to believe that “it is not the same thing to have known Jesus as not to have known him, not the same thing to walk with him as to walk blindly, not the same thing to hear his word as not to know it, and not the same thing to contemplate him, to worship him, to find our peace in him, as not to” (Evangelii Gaudium, 266), if the very words we use to communicate our experience no longer make sense to those around us?

The first step is interior: allowing ourselves to be more fully converted each day, to be set free from the temptation to settle for a superficial knowledge of the comfortable catch-phrases we learned in catechism class, to be drawn more deeply into who God is. The words that define the Christian life—the Gospels, the Creed, the Hail Mary, the Our Father, and all the rest—are perpetual sources of rejuvenation, places where our own lives with Christ can be renewed and made more real. For these words to speak most effectively to others, we have to be willing to let ourselves be changed by them. We ourselves need to be transformed by the awe-inspiring experience of “how good it is to stand before a crucifix, or on our knees before the Blessed Sacrament, and simply to be in his presence!” (EG 264).

When we allow Christ to be our teacher in this way, we allow him to give us a new language to speak with. We begin to share in “how accessible he is” (EG 269), and are made more able to reveal Christ’s transforming love to people who don’t speak God’s language. Jesus’ Precious Blood is totally adipsous; but until we let him quench our thirst, we will not have much luck inviting others to drink from that life-giving stream.

Ultimately, this is the secret to evangelization: knowing that we are not going to save our friends by our own power or through our own eloquence. Salvation is from Jesus Christ, and him alone. That means we don’t have to be afraid of our own weaknesses, of the frailty of our language. Jesus Christ draws men and women to himself because he is true, good, and beautiful. If we give ourselves to him, and allow him to speak through us, trusting in his mercy, our contemporaries may discover that the Body and Blood of Christ are rather welcome nutrition after all.

✠

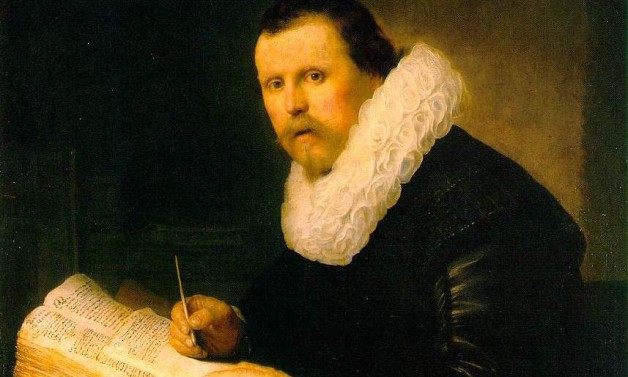

Image: Rembrandt, A Scholar