On July 2, 1776 the Second Continental Congress declared our independence from England. Two days later, on July 4th, the final text of the Declaration of Independence was adopted. Offering the correct explanation for secession was of such importance to the Founders that agreeing on the language of the document took them two days longer than agreeing to take the revolutionary act itself.

More than half of the Declaration is spent listing the grievances against King George III, but it is the iconic second paragraph that has given the document its perennial significance: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” The United States—the Declaration is the first official document to use that name—begins with the recognition that rights have their origin in God, not government.

There are many atheists and secularists who will go to great lengths to deny the Christian origins of the United States. But even if many of the founders were deists, it is telling that the first sentence of our founding document appeals to God’s authority:

When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

Not only are we endowed with rights by our Creator, but the “Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God” are what entitle a people to the power of political self-determination.

The Declaration of Independence sought to demonstrate that the American Revolution, which was in fact already underway, was not merely the temper tantrum of wealthy merchants who felt overtaxed, or of colonial politicians who felt ignored. Instead, it was a just claiming of God-given rights. Because they are God-given, these rights are beyond the control of kings and parliaments; they belong to us by virtue of our humanity, not by virtue of an all-powerful government.

The founding premise of our republic is that rights were not Parliament’s to give, but belong to us as human beings. If rights come from the government, our revolution would have been illegitimate and our independence merely the consequence of defeating the British in battle. The justification for our fight for independence was not “might makes right,” but rather the belief that we have “certain unalienable rights,” which must be defended.

Over the years we as a people have lost touch with the source of our rights. In the 112th Congress alone (2011–2012), senators and representatives have introduced the Pilot’s Bill of Rights, the Bereaved Consumer’s Bill of Rights, the Student Bill of Rights, the Women Veterans Bill of Rights, the Injured and Amputee Veterans Bill of Right, the Airline Passenger Bill of Rights, the Commercial Privacy Bill of Rights, the Home Care Consumer Bill of Rights, and the International Travelers Bill of Rights. This plethora of enumerated rights runs the risk of obscuring the divine source of our rights. Rights are those things that are our just due. And while there certainly are things that are justly due to pilots, consumers, students, and women veterans, we must never lose sight of the fact that the moral foundation of justice is man’s unique dignity as a being made in the image and likeness of God. Without this divine foundation, rights are reduced to mere social conventions, legitimated only by the might of the powers that be.

As we confront a political class that is increasingly hostile to the free practice of religion, let us be ever mindful that the document that gave birth to our nation’s independence acknowledges that our rights come not from the government, but from almighty God.

✠

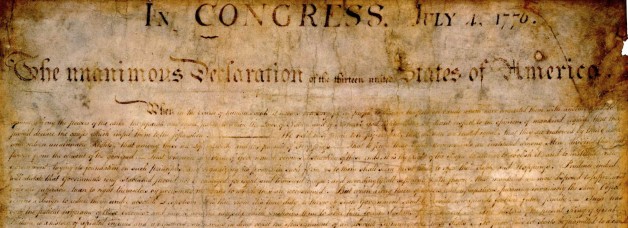

Image: The Declaration of Independence