Wolfgang Petersen’s 2004 film Troy portrays the mythical Achilles as “a real man,” renowned for his forcefulness, physical strength, and military tact. However, consider Homer’s full portrayal of Achilles in the Iliad, starting from the very first lines: “Anger be now your song, immortal one, / Achilles’ anger, doomed and ruinous, / that caused the Achaeans loss on bitter loss.” Achilles, ruled by the passion of anger, creates a vortex of infighting with his allies, womanizing, sullen brooding, histrionics, desecration of temples, and many violent murders. The passions govern Achilles’ life. According to Aristotle, those who “have strong passions and tend to gratify them indiscriminately” are called “the youth”: “They are hot-tempered and quick-tempered, and apt to give way to their anger” (Rhetoric, 1389a2-8). In actuality, Achilles is not “a real man,” but only an adolescent. Physically an adult, but psychologically stalled in boyhood, he lacks a stable, virtuous, and integrated masculinity. As such, he lives a pathetic and fundamentally unhappy life governed by ephemeral pleasures and emotional vacillations.

Things are not necessarily better today. Michael Kimmel’s book, Guyland explores the attitudes and behaviors of 22 million American “guys” between the ages of sixteen and twenty-six who are “poised between adolescence and adulthood.” As opposed to Achilles’ military exploits, these “guys” indolently seek happiness in the pleasures of video games, drinking, hooking up, and watching sports. Despite all these apparent satisfactions, they frequently “feel anxious and uncertain” (3). Representing the other end of the spectrum from Achilles’ toxic masculinity, these “guys” are unhappily emasculated.

Both Achilles and “guys” are trapped in perpetual adolescence, and neither have found happiness. As maladjusted adults, they lack authentic masculinity. This highlights the importance of ensuring that boys today grow into virtuous and happy men tomorrow. In short, boys ought to receive a deliberate and thoughtful education in masculinity. This involves all educators: teachers, parents, coaches, professors, etc. Their job is to guide the boy into his full humanity and masculinity, so he can live happily. “Masculinity” is not knowledge nor a skill, and so it cannot be taught in the same way as biology or rhetoric. The best way to guide a boy in his understanding of masculinity is to provide examples of happy men, which the student can examine and emulate.

Guided by Examples

The twentieth century philosopher Jacques Maritain, in his book Education at the Crossroads, asserts that the aim of education “is to guide man [i.e. all human beings] in the evolving dynamism through which he shapes himself as a human person―armed with knowledge, strength of judgment, and moral virtues” (10). Note that there are two central elements of education: the goal and the method. The goal is for the student to become a fully developed human person. The method pertains to the educator as a “guide.”

With respect to the goal Maritain notes that “education is not animal training. The education of man is a human awakening” (9). By contrast, the last century of education theory in America has prioritized pragmatism, socialization, and technical-scientific skill, ignoring deeper needs of human development. The result is a generation of “guys” who have completed university studies, but remain listlessly unaware of who they are as persons. Schools ought to play a role in awakening youngsters to their full humanity, which includes boys awakening to their masculinity (and girls to their femininity). Teaching masculinity does not mean simply preparing boys for “masculine” professions, or playing “masculine” sports, or following some “manly handbook.” Masculinity is not a pragmatic skill to be developed, rather it requires self-awareness.

Educators (both parents and teachers) guide their students. The educator cannot compel a student to learn, nor can he carry a student along the path toward knowledge. John Dewey, the American philosopher of education, likewise noted, “the young, after all, participate in the direction which their actions finally take. In the strict sense, nothing can be forced upon them or into them” (Democracy and Education, 25). The student has real agency in his education, and therefore “the only way in which adults consciously control the kind of education which the immature get is by controlling the environment in which they act, and hence think and feel. We never educate directly, but indirectly by means of the environment” (19). A teacher could didactically tell a boy all about masculinity, but ultimately the child through the course of his life will need to discover for himself what it is to be a man. He sees this from the examples of men he knows personally, but also from fiction and history. Thus, for a boy to grow in an understanding of his masculinity, he must see positive examples in his environment. These might be men he knows personally or those of history. Maritain proposes that “the saints and the martyrs are the true educators of mankind” (25). Thus, we will examine several Dominican saints which can reliably serve as guides towards virtuous masculinity.

Lastly, Maritain lays out four fundamental norms of education. Educators ought to liberate their students, develop their student’s spiritual life, foster a student’s interior unity, and finally give the student a mastery over reason. Maritain proposes these norms for teaching in general, but they can be applied to any specific topic. These four norms provide a reliable framework for how educators can guide its students to an understanding of themselves as persons, and especially how boys can learn masculinity. We will discuss each norm, and show how a particular male saint has learned its lessons to the fullest. In this way the saint provides an example which will guide boys to a happier adulthood of masculine virtue.

Bl. Pier Giorgio Frassati and Liberation

For Maritain, the task of education is “above all one of liberation” (39). Education ought to be a process primarily of enlightenment, encouragement, and illumination, not of repression and prohibition (though these may have a secondary role). When teaching boys to be men, we ought not focus on purported rules of masculinity, such as “boys don’t cry.” Rather the process ought to bring young men to the freeing life of virtue. Maritain goes on to explain that “the real art [of education] is to make the child heedful of his own resources and potentialities for the beauty of well-doing” (39). A child in school spends much time trying to discover his talents and to learn how to fully use them. One child may discover that his or her potentialities include physical height and so set out to apply this resource to well-doing on the basketball team. Another may discover a musical ear, and therefore realize a part of his or her humanity in the orchestra. In a similar way, masculinity is one of these resources which males possess. Education ought to make the boy “heedful” of his masculine potentiality and help him apply it virtuously in the “beauty of well-doing.”

A poor education in masculinity would result in a boy’s potentialities being directed away from “the beauty of well-doing.” Achilles gives us an example in which the process has failed. He has taken the resource of his masculinity and its propensity toward physicality and directed it toward the vices of rashness, envy, and conceit.

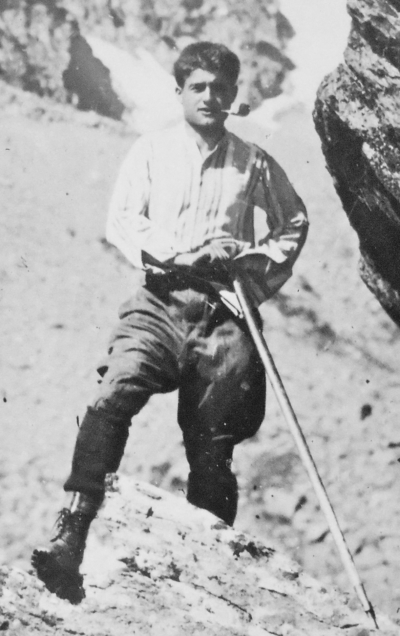

By contrast, Bl. Pier Giorgio Frassati provides a saintly example of a liberating education in masculinity. In 1925 he died at that age of twenty-four, but by then he had already become “heedful” of his resources. A physically strong and active young man, he dedicated himself to mountain climbing, though not for personal aggrandizement. As Pope John Paul II observed while visiting the mountain town of Cogne, “He daringly explored the peaks towering over it and made each of his ascents an itinerary to accompany his ascetic and spiritual journey, a school of prayer and worship, a commitment to discipline and elevation.” Unlike Achilles, Frassati took his physicality and applied it to a life that would lead him toward virtue.

Bl. Pier Giorgio Frassati

St. Dominic and Spiritual Dynamism

In his second norm, Maritain asserts that education ought to “center attention on the inner depths of the personality and its preconscious spiritual dynamism” (39). A full education cannot be confined only to cursory knowledge of pragmatic subjects. There is a laudable trend in education today to focus on STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics). However, even back in 1943, Maritain recognized that excessive “scientific and technical specialization . . . dehumanizes man’s life” (19). This is because humans are not merely specialists. Animals are specialists. Bees perfectly specialize in skillfully making honey, and beavers dams. Educating humans is not mere animal training but most importantly develops a flourishing of human reason, spirit, personality, and interiority. In too many schools “the internal world of the child’s soul is either dormant or bewildered and rebellious” (19). When teaching boys, it is not enough only to examine the biological (material) components of being male. Rather, the boy ought also to learn that mature and happy men possess a “spiritual dynamism.”

Lack of attention to the interior life has consequences for modern masculinity. In Guyland, Kimmel proposes an explanation for the unprecedented media consumption among males ages 16-26. Kimmel posits that media use allows men “to spend time together without actually having to talk about anything significant that might be going on in their lives. In fact, in many cases . . . to avoid what’s going on in their lives. All these distractions together comprise a kind of fantasy realm to which guys retreat constantly . . . because it’s a way to escape . . . their tedious, boring, and emasculated lives” (147). Many modern adolescent males find their lives tedious, boring and emasculated precisely because they lack an interior life. Periods of quiet and reflection allow persons to recall their memories, develop their hopes for the future, and become fully present to themselves. Through an interior life a person can develop self-awareness and self-possession, which become the foundations for a person’s ability to become a real actor in his own life. Without an interior self-possession persons live their lives continually acted upon and without taking deliberate action. Many modern males are inert because their education at home and at school failed to alert them to their spiritual dynamism, perhaps giving a limiting focus to skills and specialization in an academic field, athletics, the chess club, etc. As young adults, this stunted interiority is compounded by media consumption which acts as a type of morphine drip that desensitizes these men to the abyss within their own soul.

For an example of a vibrant interior life, we can turn to St. Dominic de Guzman. Born in Spain and educated at a cathedral school, he specialized in rhetoric, logic, and argumentation. In founding and governing the Order of Friars Preachers, he displayed significant administrative skill. Yet specialization and skill was secondary to his interior life of prayer. As described by the Dominican spiritual writer Bede Jarrett, “prayer for him was an energetic conversation with God” (Life of St. Dominic, 109). He would spend long hours at night alone in the chapel, clearly comfortable with solitude. In this way, he can show even to modern boys an example of a man with the courage and strength to live a dynamic spiritual life, fully aware of his own soul and of God.

Fra Angelico and Internal Unity

The third norm focuses on the need to “foster internal unity in man” (Maritain 45). This means that education focuses not only on the mind, but the body as well. To this end, schools ought to attend to the student as a body-soul composite, educating the intellect, but also encouraging physical play by teaching sports, mechanics, and the arts. Maritain asserts that nearly everything has a place in school, including bee-keeping, jam-making, and “rustic lore” (whatever that may be) (55). Unfortunately, many schools have cut back their offerings in athletics, shop class, and the arts. The result is a high emphasis on the mental component of a person, which can lead to a certain imbalance and disintegration.

Our examples of maladjusted men show what can occur when this internal unity is undeveloped. Homer presents Achilles as a dehumanized warrior without much intellect, whose allies seem to rely on him only for his physical prowess. He lacks authentic masculinity because his body is dominant to the detriment of his mind. By contrast, Kimmel’s “guys” live a disembodied life, prefering to watch sports instead of play them. These “guys” live in their heads, unconnected to their own bodies.

The true man fully integrates mind, body, and spirit. For an example among the saints, we might turn to the early Renaissance painter, Blessed John of Fiesole, better known as Fra Angelico. A Dominican Friar in Florence, his most famous frescos adorn the walls of the Convent of San Marco, where he lived, studied, and prayed for ten years. As a Friar Preacher, he spent his youth studying philosophy and theology, along with a life of prayer. Having lived a life of words he integrated the intellectual and spiritual dimensions with the somatic dimension of his person through his many paintings, works of his own hands. As the Dominican historian Guy Bedouelle notes, “art was, for him, the prime medium of preaching (In the Image of Saint Dominic, 76). Fra Angelico not only learned theology through academic study, but he gave it physical form in his frescoes. Thus, because of his fully integrated humanity, we see that as a man, Bl. John of Fiesole was able to portray truth to the world with self-confidence. What a contrast to Achilles’ conceit and boastfulness, or the “guy’s” timidity.

St. Thomas Aquinas and the Mastery of Reason

In the fourth and final norm, Maritain suggests that education ought “to libertate intelligence instead of burdening it, in other words, … freeing the mind through the mastery of reason over the things learned” (49). Ideally, a student should not only know facts and information, but should also have a command over that information. Furthermore, they should interact with questions which lead them to a deeper understanding of the world, instead of being simply burdened by sophististry and skepticism. James Schall notes that modern young adults “simply have never had the things that really matter clearly and adequately exposed to them. . . . [They are] not really encountering the great questions and, what is more important, the great answers. Education is not just a series of questions. Rather it is mostly a series of answers” (“On the Education of Young Men and Women” in The Common Things: Essays on Thomism and Education, 141). Modern schools and universities often raise doubts about everything. While questioning is important, the ultimate goal of education is finding an answer. If students leave school with only doubts and no answers about life, they have not really received any education at all.

Perhaps this is the cause of some of the disintegrated masculinity explored in Guyland. Young men learn many things while in school, but often they have not learned to apply this learning to exert any agency in the world. As Kimmel notes, “today’s young men are coming of age in an era with no roadmaps, no blueprints, and no primers to tell them what a man is or how to become one” (42). Adolescent boys, especially those with a university education, are surrounded by questions and doubts about what it means to be a man in the world today. Frequently, important questions about gender roles unfortunately stop with asking questions; the conversation ends without providing much of an answer.

Maritain posits that Thomas Aquinas would describe the situation as digging a ditch in front of youngsters, but then failing to fill it up (Maritain, 50). While Aquinas himself has little to say on the subject of masculinity in particular, he himself provides an excellent example of a man who has achieved a “mastery of reason over the things learned.” In his incomplete masterwork, the Summa Theologiae, he proposes nearly 3,000 questions ranging from “Whether the brave are more eager at first than in the midst of danger?” (I-II, Q.45, Art. 4) to whoppers such as, “Whether God exists?” (I-I, Q. 2, Art. 3). For each of these questions, Aquinas provides a thorough explanation of his position, drawing upon an extensive knowledge of philosophy, theology, history, and the best science of the day. His life and works show what it means to have full command over things learned and to direct oneself toward the search for Truth. Boys cannot live in perpetual doubt about the meaning of their masculinity. They should be guided by Aquinas’s example of applying their intellect to finding the answer.

Lifelong Learning

It is important to note that an education in masculinity is not a male project only. Women also play an important role in teaching boys how to be virtuous men. In his reflection on Genesis, Kenneth Schmitz notes that Adam comes to know his masculinity only after the creation of Eve: “Man as male comes to a new self-awareness and self-realization only with the coming to being of man as female. . . . the process of self-recognition occurs in the woman as well” (At the Center of the Human Drama, 102). Teaching masculinity must also involve a boy’s mother, sisters, girlfriends, (later) wife, and the example of female saints. Through a healthy relationship with women, boys can become aware of their own masculinity.

A reactionary mindset might assert that men were more “manly” in the past, while a progressive mindset asserts that men are universally better off today. However, both ancient Achilles and modern “guy” culture suggest that neither is the case. Without deliberate guidance, boys can develop all types of disordered masculinity. Careful attention to the educational environment will bring boys toward a self-aware and healthy masculinity. The saints provide great material for this education, and Maritain’s norms provide a method. However it is important to emphasize that, “our education goes on until death” (Maritain 25). It would be impossible to expect that at the end of his schooling a boy would emerge as a fully constructed man, as if from an assembly line. Knowledge of masculinity is not technical, practical, or intellectual, but connatural, the result of years of reflection upon many virtuous examples.

✠

Download a PDF of this article here.