The Need for Order

If sons learn masculinity from their fathers, contemporary art is an absentee father. I contend that, today, one cannot find an exhibition that truly displays masculinity. The MoMA (Museum of Modern Art) of New York in its recent gallery session, The Aesthetics of Gender, posits that gender is “one of the most fluid concepts of the past century.” From the mid-twentieth century, art depicting human sexuality has combated traditional notions of a man’s character, role, and actions. Moreover, artworks inspired by gender ideologies distort masculinity and femininity more than Picasso’s analytic cubism distorts the human body.

Two pitfalls of contemporary works are lewdness and stereotypes. Artists employ lewdness in these exhibitions in order to counter the voyeuristic depictions of the female body that began to appear in nineteenth century. Édouard Manet’s, Olympia (1865) and Paul Cezanne’s, The Bathers (1898-1905)—works not overtly lewd in themselves—inaugurated a movement that exploited the female body. Today, a similar movement exploits the male body. The other pitfall, stereotypes, appears in works that portray masculinity as femininity. Wishing to tear down traditional views, artists cast men in a feminine light by taking stereotypes of women and depicting men according to those stereotypes. Men appear dressed in high heels, marked in cosmetics, and in poses typically found in the pages of women’s fashion magazines. The same artwork emphasizes flaws like fragility, vulnerability, sensitivity, or vanity as the other side of masculinity. Ultimately, these works reinforce a misogynistic world view. As a result, contemporary art does not provide a positive and true representation of masculinity.

Some works of art criticize the objectification of the female body and challenge rigid stereotypes that are reductionistic. We can applaud these efforts which call for the respect of human dignity and a proper understanding of human sexuality. Unfortunately, the contemporary art world’s attempts do more harm than good, because these works are disturbing and pornographic. This disregard for the holiness of the body poses an insurmountable obstacle for this essay’s engagement with these works.

Refusing to enter the museums of contemporary art, this essay will walk the halls of classical art in order to find true, positive depictions of masculinity as well as negative examples. These depictions avoid lewdness and stereotypes because their artists portray men and women with a deep, philosophical understanding of the human person. This philosophy owes its insight to the narrative arc of Scripture: from the creation and fall of Adam and Eve to the Holy Family of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph. Edith Stein, a Catholic saint and penetrating philosopher, artfully divides the narrative arc of man and woman found in Scripture into three orders: the original order, the order of fallen nature, and the order of redemption. This essay will examine artwork depicting man and woman in all three of these orders, contemplating the masculine figures and their life within the family.

The Original Order

Lucas Cranach the Elder, in his expansive painting of 1530, The Garden of Eden (see figure 1), captures the formation and life of the first man and woman. Cranach depicts the creation of Adam as a formless child in the top-right corner of the painting. The rendering is incomplete, signifying that he still awaits ensoulment. God, clothed in a brilliant red garment, blesses Adam with his right hand as he places his left hand on his creature’s head. Further back in the painting, God pulls Eve, fully formed, from the side of Adam. Centered, large in the foreground, the two converse with God, standing face-to-face with him. God, with his hand in benediction, blesses the couple as he commands them to be fruitful, govern creation, and refrain from eating the fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. Their failure to obey results in the last three images: their fall by the serpent, their hiding from God, and their expulsion from the garden at the behest of a sword-wielding angel.

The landscape is wide with the horizon high in the composition. Cranach has focused the viewer’s gaze toward the earth, the garden. He depicts its tranquility unchanged by multiple events taking place. Even the thud of Adam and Eve’s sprint in the scene of expulsion cannot be heard over the trickling spring bursting from the mountainous rock in the background—an allegory to the font of grace, Jesus Christ. The beasts in the garden sit peacefully next to each other without fear of attack. Adam names these creatures horse, deer, boar, and dog—here depicted domesticated and curled up peacefully next to his master’s feet—and he and Eve reign over the created world as benevolent stewards. The wheel-like arrangement of the figures connotes a peaceful turning, resembling something of a dance. All seems to move from and return to the central figures. The painting communicates the harmonious concord which was lost by the original sin.

Edith Stein reflects on the original order of Adam and Eve before the Fall, and she concludes that they had a life of “the most intimate community of love” (Stein, Essays on Woman, 62). Before tasting disobedience, the two lived in harmony, right relation, and without conflict. Stein stresses that the sovereignty of man over woman did not exist in the garden, because there was no resistance to the order of love which God created. Cranach captures this equality in the foreground of the painting where Adam and Eve stand together mirroring God whose image they each possess.

In this community of love, according to St. Thomas Aquinas, Adam and Eve are both truly equal and truly distinct. Because both sexes fully possess the image of God, each of them naturally has the capacities that properly flow from human nature: the abilities to know the truth and love the good (Summa Theologiae I, Q. 93, a. 4). For this reason, Aquinas ascribes all the virtues to both men and women—a controversial intellectual position at the time. Adam and Eve easily, promptly, and joyfully sought the good of the other and the good of all creation. They are meant to love one another and join hands as corulers. Their equality, rooted in the image of God, human nature, and the virtues, coexists with their distinct sexualities. Aquinas believes that the distinction between male and female is so proper to human nature that it will even be present in the new garden after the resurrection of the body. The glorified bodies of men and women will truly be masculine and feminine bodies (though there will be no procreation), because sexual difference belongs to the perfection of human nature (Summa Contra Gentiles, IV, 88).

Cranach expresses these philosophical truths in his own medium. In his painting, Adam and Eve mirror God as creatures possessing intellect and will. They hold hands, standing together before God as bride and groom: wedded as equal members of a communion of love. One is not more human than the other, but neither epitomizes what is humanity. The perfection of human nature requires both man and woman. Adam’s free hand covers his heart, while Eve’s holds a piece of fruit from the garden. This fruit foreshadows both her sin and her eventual fruitfulness in marriage. Though she bears no son within the garden, Eve will bear Adam a son in exile forming the first family.

The Order of Fallen Nature

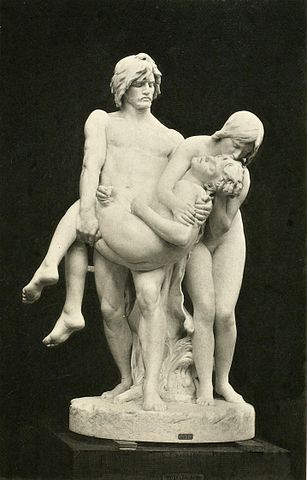

After bearing children, Eve suffers what all mothers would come to fear, the death of her son. Louis-Ernest Barrias’ marble sculpture, The First Funeral (1883), though it is an extra-biblical account, captures the reality of the first family’s plight (see figure 2). He sculpts Adam and Eve carrying the remains of their son, Abel. Cain, their first born, is not present in the scene. God had banished him after the murder, and he became a son estranged from his mother and father. Lying motionless in his father’s arms, Abel represents both the fruit of his parents’ love and and the fruit of their sin, for they brought new life into the world as well as sin and death. Adam leans back, balancing the weight of Abel and recoiling from death’s repulsiveness. Eve presses her lips upon her son’s head, likely where the fatal blow was struck. In Cranach’s wedding scene she held fruit, while here she kisses the fruit of her womb and the fruit of her sin. The scene captures the first funeral but also all funerals. The first family which grew from the parents’ love also declined because of their sin. The disorder of man-to-woman and brother-to-brother relations creates an endless cycle of ruin, one that calls for redemption.

Edith Stein names this ruinous cycle the order of fallen nature. Whereas Adam and Eve enjoyed a harmony in the Garden of Eden, they now find dissonance between themselves and creation. In the original order, Adam and Eve had undisputed sovereignty over earth. Cranach demonstrates this by the teeming fruit and peaceful animals in The Garden of Eden. In the order of fallen nature, man is punished by natural disasters, dangerous or stubborn animals, and vegetation that is barren. All the forms of being resist man: vegetative beings require toil, sensate beings attack man or stubbornly refuse his guidance, rational human beings kill one another, and even spiritual beings—like Satan tempting Adam and Eve in Cranach’s painting—oppose man. Man toils for existence, and this toil and dissonance is present in the hands of Adam in The First Funeral. He carries the burden of his son and the burden of our fallen world.

These disruptions in harmony of the natural world reflect a disorder within fallen human nature itself. Man and woman, Adam and Eve, resist God and one another. Having lost their innocence, the first couple sees their nakedness, and attempts to hide, as depicted in the top-left of Cranach’s painting. In this scene, God, who in other scenes walked the earth with Adam and Eve, now stares from the clouds in disapproval, a sign of the fractured relationship. God punishes woman stating, “I will intensify your toil in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children. Yet your urge shall be for your husband, and he shall rule over you” (Gen 3:16). The concupiscence of the flesh inclines Adam and Eve into a relationship wrought with difficulty. Eve must become vulnerable and bear pain, and she must additionally follow the lead of another, one who will be imperfect, one who failed to protect her from the serpent.

Conversely, Adam’s punishment is to toil the earth until it brings forth fruit. Adam must rule, guide, protect, and provide for Eve and their family. The First Funeral shows that he is the head of the family by his prominence; his head is the highest point. His strength, meant to protect the family, is shown in his muscles which flex under Abel’s weight. However, Cranach in his painting shows that Adam’s protection may work against Eve. In the scene of expulsion, Adam grabs Eve’s arm with a forcefulness indicating the plague of man’s dominance. But in Barrias’ sculpture, Adam’s strength failed to protect Eve from undue suffering; she weeps over his failure.

Man’s strength is meant to assist him in protecting and providing for the family, but in the order of fallen nature it can instead become a weapon to ensure his headship. On the sacristy ceiling of Santa Maria della Salute in Venice, Titian’s painting, Cain and Abel, captures the brutality of man’s domineering strength (see figure 3). The billowing smoke of Abel’s sacrifice fills the air with a dark aura. God had accepted Abel’s sacrifice in an exclusive manner leaving Cain furious at being denied God’s preference. From a low perspective, we look up at Cain as if we ourselves are to bear his blows. Abel’s blood is already speaking as it falls from the gash in his head. Cain lusted for supremacy, placing his brother under his feet. Cain’s famous words, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” (Gen 4:9), could very well be understood as, “I am my brother’s conqueror.”

Cain, who employed his strength against his own brother, demonstrates that masculinity corrupts into an unhinged virility. Masculinity is the proper ordering of man’s sexual faculty and energy toward procreation and family governance; it is geared toward love. Virility is the abuse of man’s sexual faculty and energy for his own pleasure and dictatorial power; it is geared toward selfishness. The masculine man seeks fatherhood, but the virile man seeks supremacy.

Art for many centuries has captured this distortion of masculinity. Ancient Rome and Greece captured the virile man in its representations of male gods and soldiers. Both are shown as slaves to their lust for power and pleasure. The Renaissance took two themes commonly depicting this virility, The Rape of the Sabine Women and The Rape of Proserpina. Nicolas Poussin’s The Abduction of the Sabine Women (1634-1635) shows a chaotic scene of armed Roman soldiers carrying flashing steel and screaming women as their spoil. Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s The Rape of Proserpina (1621-1622) depicts a hulk-like Pluto tearing a tearful Proserpina from the land of the living to the underworld (see figure 4). Unlike Cranach’s depiction of marital equality before God, we have a pagan god snatching his woman. Whereas Adam and Eve stood on equal footing, here Pluto lifts Proserpina from her very feet. His strength is manifest and undeterred by the violent and desperate thrashings of his victim. Even the benevolent canine in Cranach’s painting contrasts with the hellish, three-headed Cerberus, who extends the imagery of violence, brutishness, and horror. Bernini’s work, like so many others, broadcasts fallen man’s power to conquer, dominate, and spread his seed. In the order of fallen nature, misguided masculinity devolves into a slavish virility, and its character is arrogant, confident, and indifferent to woman.

The Order of Redemption

The order of redemption witnesses man turn away from slavish virility and move toward true masculinity, which is comprised of service, sacrifice, and the reordering of the fallen world. El Greco captures this with his classic vermicular brushstrokes in his portrayal of St. Joseph in The Flight into Egypt (ca. 1570; see figure 5). El Greco emphasizes the drama of the flight with the swirling clouds in the sky. This ominous scene portrays a perilous journey, and Joseph heroically takes the reins of the situation. The style of the painting wisps like the smoke of incense rising up to God as a pleasing offering. As he leads his family from the destructive virility of King Herod’s persecution, Joseph fulfills his truly masculine roles as provider, protector, and administrator to the Holy Family.

Like Adam in The First Funeral, Joseph stands prominent in the composition. Yet, while Adam failed to save his son from death, Joseph, aided by God, protects the Christ child as he leads his family to safety. He is so successful that Leo XIII writes, “men of every rank and country should fly to the trust and guard of the blessed Joseph” (Quamquam Pluries, 4). His traveler’s staff signifies his position as head and protector of the family. Mary, seated upon a donkey with Jesus, is vulnerable and attentive to her Son. Joseph must lead them to safety and provide for their wellbeing. Danger and scarcity loom. Joseph, whose staff points directly upward to God, finds his strength above. The sun glistening on his bald head signifies the light of wisdom that rules him. He provided for Jesus so fully that the Church remembers Joseph in the Mass. St. John Paul II acknowledges this honor: “In the Eucharistic Sacrifice, the Church venerates . . . the memory of St. Joseph, because ‘he fed him whom the faithful must eat as the bread of eternal life’” (Redemptoris Custos, 16).

In addition to providing for, protecting, and leading his family, Joseph also manifests a reordering of creation back to its original harmony. The donkey, an animal of stubbornness, represents the obstinacy of all the animal kingdom. However, Joseph manages to turn the donkey, coaxing the animal into service. By this action, Joseph represents Adam before the fall, who governed the animal kingdom with ease. The order of fallen nature turns toward the order of redemption. Joseph not only leads his family, but all of creation as well.

Whereas El Greco renders Joseph’s masculinity in the public realm Bartolomé Esteban Murillo captures Joseph in the intimacy of the home. Murillo’s painting, The Holy Family with a Bird, pictures Joseph’s unique vocation of bringing the mystery of the Incarnation into the family (see figure 6). His fatherhood of Christ was not from procreation but virginity. Though virgin, his fatherhood truly took on all responsibilities proper to the vocation of a human father (Redemptoris Custos, 21).

In contrast to the turbulence of El Greco’s painting, Murillo’s domestic scene pictures the Holy Family in a quiet moment of play. The peace in the home is the fruit of Joseph’s success as the head of the family. Christ holds a bird, a creative adaptation of Federico Barocci’s La Madonna del Gatto (1575) in which John the Baptist teases a cat with a European goldfinch. This ornithological symbol—first appearing in Da Vinci’s Madonna Litta (1475)—represents Christ’s future Passion, because the red-faced bird eats among thorns. The Christ child holds the symbol of his Passion in the air, lifting it high. Joseph had the vocation of rearing his son for the moment at Calvary when he would lift up the Cross and be lifted up himself upon it. However, the looming Cross does not cast a dark shadow on this peaceful moment. In this home, Joseph steps away from his work, which lies in the background, and he sits intimately with his adopted son. At some point, all fathers must put down their work and attend to their children. Unlike the brokenness seen in The First Funeral, this painting captures a father, mother, and son in the joy of life. Has not God worked through Joseph in order to provide for this moment? Even the dog, a common sign of the harmony of the domestic life, seems taken by Joseph’s family, and his sportive appearance evokes the tranquil canine at Adam’s feet in Cranach’s painting above. The dog is a far cry from the untame, ravenous monster at the feet of Pluto.

Joseph taught Christ industriousness, the priority of the interior life, and the quiet love of domestic life. Joseph’s masculine vocation did not stop at providing sustenance or worldly care, he had to raise Christ in the faith. Stein writes that a man in the order of redemption “should consider his greatest mission to lead the entire family in the imitation of Christ and, according to his powers, to further all seeds of grace which are stirring in them” (Essays on Woman, 77). Joseph had the vocation to ensure his son’s grace abounded. Following Jewish custom, Joseph took Jesus to Jerusalem on solemn feasts, brought him to the synagogues, and taught him prayers. In doing so, Joseph as head of the family imitated his son of divine origin, who would eventually reveal to man the highest form of masculinity. Joseph had the task of raising the very one who would become the example of all. With a father’s love, Joseph prepared Jesus to manfully take up the Cross, the symbol of which the child holds in Murillo’s painting.

Peter Paul Rubens’ Christ on the Cross between the Two Thieves (1619–1620) displays the highest form of masculinity (See figure 7). The pastoral constitution of Vatican II, Gaudium et Spes, explains that Jesus takes the place of Adam in order to reveal man to himself and to make his call clear (GS 22). Christ—offering himself in perfect charity upon the Cross—reveals a masculinity that provides, protects, and administers, not only with regard to his own family, but to all families. In caring for the universal family of God, Jesus extends beyond the masculinity of Joseph. This is the true manhood of the order of redemption, a masculinity for a spiritual family united in charity.

Christ protects many people from the Cross. On the left-hand side of Rubens’ painting, the good thief reaches out so as to touch Jesus, his salvation. Before this harrowing scene, Christ prayed for the very men who pierced him: “Father, forgive them, they know not what they do” (Lk 23:34). Rubens captures in this Crucifixion the sign that protects all Christians from the assaults of the devil. The Lord upon the Cross becomes the image of protection. Rubens artfully paints the moment at which the blood and water burst from the side of Christ. The centurion piercing Jesus—tradition calls him the converted St. Longinus—sits underneath the spray, unknowingly awaiting its protective covering.

Rubens’ painting also shows Christ providing for his Church, the family of God. Unlike St. Joseph who toiled in order to provide perishable food for his family, Our Lord hangs upon the Cross offering his very self as imperishable food. He says, “For my flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink” (Jn 6:55). The bloody sacrifice on Calvary is the bloodless sacrifice of the Mass. The Eucharist becomes the food that contains every blessing. So powerful is Christ’s provision that anyone who eats of it will have eternal life (Jn 6:54). Rubens depicts a strong, masculine body given up for the life of the world. Perhaps he wished to evoke the idea of eating when he painted the soldier’s horse in the bottom-left nipping at its own flesh.

In the bottom-right of the painting, the effects of Christ’s administration on the Cross take place. Rubens depicts John holding his new mother who is lost in sorrow and contemplation. Upon the Cross, Jesus established Mary as the mother of the Church, and John beholds her (Jn 19:26–27). Mary recognizes that her son has given his whole Church to her. She is the new Eve, and he is the new Adam. The note at the top of the Cross expresses in three languages that Jesus is King, a mocking claim that paradoxically rings true. Christ’s reign extends to all nations, but he wears a crown of thorns. His kingdom is one of masculinity, not virility. Rubens depicts his kingship with the faint glow of a halo.

Even in the tumult of this scene—which has the same sky as Titian’s painting of Cain slaying Abel—we see Christ reordering creation. The animal kingdom, represented by the horse in the bottom-left, lowers its head for the king. In the top-left corner, we see that even the celestial spheres of creation become subject to man. The sun refuses to shine because the light of the world has been slain. It is the Incarnate Lord who “makes the sun set at midday and in broad daylight cover the land with darkness” (Amos 8:9). This darkness comes with Christ’s death, but after his resurrection, “the night will be no more” (Rev 22:5). Christ, the God-man, reigns over all of creation.

Though he reigns, Jesus did not deem equality with God something to be grasped at, he emptied himself (Phil 2:6–7). Unlike Cain, Christ did not rival God nor men, but he laid down his life on the Cross in humble obedience. The obedience he lived to Joseph found its perfection upon the Cross when he was obedient to the Father. There is no trace of lustful passion in Christ. He is pure and chaste and perfectly masculine in that state.

In emptying himself, water and blood pour from his side giving birth to the Church, his bride. As God pulled Eve from Adam’s rib, so God brings forth the Church from Christ’s side, the new Adam. His self-sacrificial love becomes the example for all men. St. Paul calls all husbands to imitate Christ, they are to love their wives as Christ loved his Church (Eph 5:25). The virile Pluto wrenches Proserpina’s body to the world of the dead, but the masculine Lord surrenders his body for the eternal life of his bride.

The Need for Art

We have journeyed through the biblical narrative of man and woman according to the three orders of Edith Stein: original, fallen, and redeemed. The artwork of Cranach, Barrias, Titian, El Greco, Murillo, and Rubens shows masculinity in its original innocence, fallen error, and graced redemption. Cranach paints the original order of Adam and Eve in which an intimate communion of love existed. Barrias and Titian’s artworks capture the effects of sin: the fracturing of the intimate communion of love and the entrance of death, rivalry, and unhinged virility. In the order of fallen nature, we also learn of the need for man to become a ruler, provider, and protector of the family. Barrias and Titian, as well as Bernini, demonstrate that fallen man is incompetent to perform his threefold responsibility. Man’s virile powers turn inward toward selfish gain. Yet, the biblical narrative does not leave man helpless; redemption comes. El Greco and Murillo paint St. Joseph as an exemplar of natural masculinity understood in the context of the family. Though Joseph does not conceive his family, nevertheless he leads, provides for, and protects Mary and Jesus. Rubens paints Christ on the Cross as the perfection of masculinity. The highest form of masculinity is spiritual, and it is properly understood as the self-sacrificial charity of Jesus Christ crucified.

These works of art represent a small portion of Scripture and of the canon of western art inspired by the Bible. In his 2009 Meeting with Artists, Pope Benedict XVI claims, “The great biblical narratives, themes, images and parables have inspired innumerable masterpieces in every sector of the arts.” These innumerable masterpieces give visual life to the scriptural narratives explored within this essay. Returning to these narratives as subjects, the contemporary artworld could find new inspiration for illustrating masculinity. Perhaps, an artist can even find an example of a Joseph or Christ within today’s world. Wherever a husband provides and protects his family or wherever a man lays down his life for the Church, the artist who paints such a scene paints masculinity. The insights that Christian thought and art give to masculinity, indeed to all human sexuality, present the contemporary artworld an alternative view of what it means to be a man. Gender is not a fluid notion, but something integral to a nature that is wounded. As it stands, we are in a fallen world, but man and woman are not meant to remain in the mire. In contrast to the libertinism of the post-sexual revolution artworld, the Church presents human sexuality without lewdness and stereotypes. This allows for healthy and pedagogical representations of man and woman.

John Paul II wrote, “The Church therefore needs art. But can it also be said that art needs the Church?” (Letter to Artists, 13). I argue, yes. The contemporary artworld has lost its ability to truly depict masculinity. Without the Church’s understanding of man, art floats adrift on a sea of fluid conceptions. The Church teaches what masculinity is from its origin, fall, and redemption. Such an understanding provides direction for the artworld which can gain sight of what masculinity is and where it is meant to go. Looking at the greatest example in Jesus Christ, perhaps the art can behold and depict true masculinity.

✠

Download a PDF of this article here.

Photo of “The Rape of Proserpina” by Int3gr4te, retrieved from commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:RapeOfProserpina.jpg, is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0