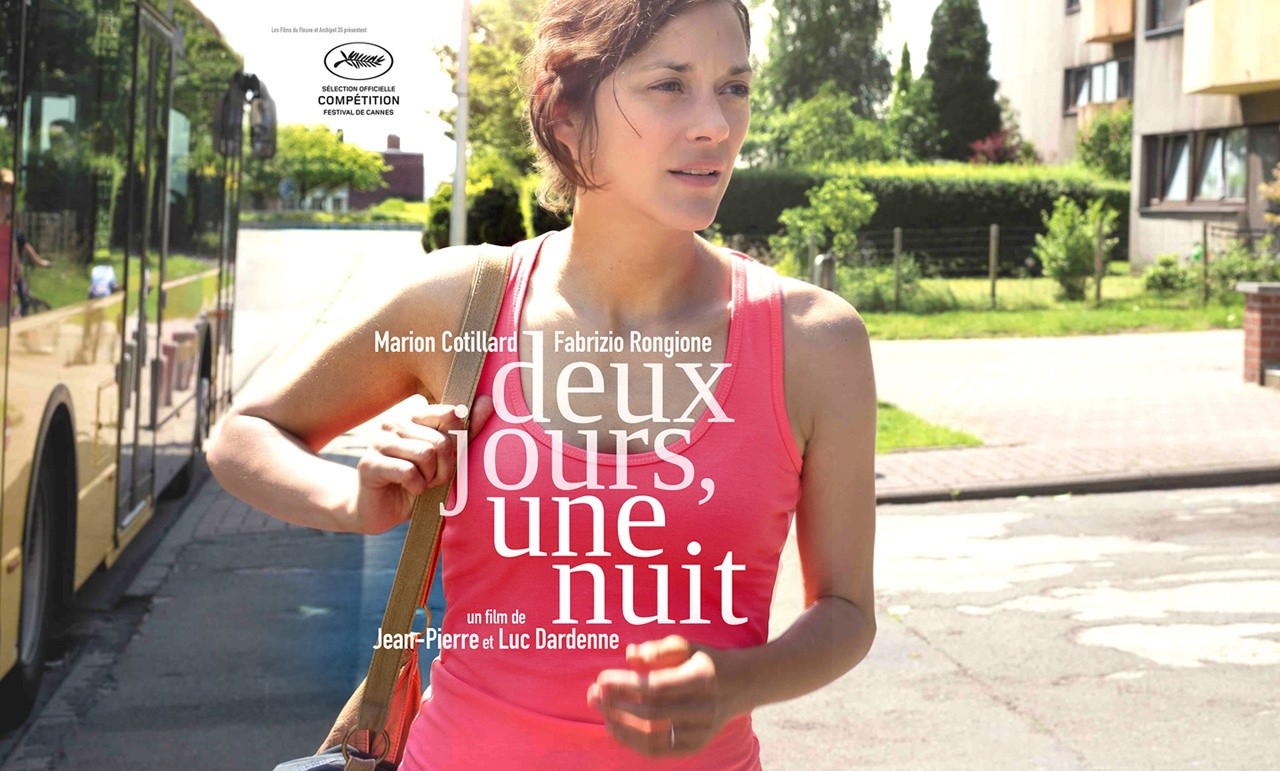

The new Dardenne brothers film, Two Days, One Night, begins with the protagonist, Sandra, played by Oscar-winning actress Marion Cotillard, receiving a call on a Friday afternoon. A coworker tells her that she’s been laid off. Sandra offers a distressed response to the caller, hangs up, and breaks down. It’s the first of a number of breakdowns as she struggles to keep her job. Sandra is a wife and mother of two who works at a solar-panel factory in Belgium, but had to take medical leave due to depression and anxiety. During her absence the management convinced the union-organized employees to vote to have her laid off so they could all receive a bonus of 1000 euros. With the support of a friendly coworker and her husband, Sandra convinces the manager to hold a second ballot and has most of the weekend, two days and one night, to convince her coworkers to reconsider her layoff.

The film offers a realistic view (often painfully so) of a human crisis. Sandra is visibly burdened with the cares of life. Family, work, the looming dole, feelings of inadequacy, and her inability to cope have left her strung out. She medicates throughout the film by popping Xanax and retreating to her room. She feels estranged from her husband and the coworkers she thought were her friends. The scenery is soul-crushing suburban. There are neither ugly tenements nor charming old-world European town squares. It’s a world of lower-middle class families, seemingly upwardly immobile, and all struggling to get by. Sandra’s physical appearance—slumped shoulders, tense jaw, bags under her eyes—shows the toll these burdens have taken.

The movie is a tale of modern family life, compassion, employee/worker relations, the issues that come with two parents working to sustain a family. But it also effectively illustrates themes of Catholic social teaching. “Economic life brings into play different interests, often opposed to one another” (CCC 2430). This insight plays out in the film and helps explain the crisis at hand. Sandra’s coworkers were given an either/or ultimatum. They could either receive a bonus or let Sandra keep her job. One coworker attempts to justify his vote and illustrates the dilemma by telling Sandra, “I didn’t vote against you. I voted for my bonus.”

One by one Sandra reaches out to her coworkers, all the while medicating her anxiety with prescription pills. The request is simple: “please consider voting for me to keep my job.” The encounters begin civilly enough, but they take different turns. The reasons proffered for voting against Sandra are on the whole not vicious. Everyone could use 1000 more euros. This money will help alleviate legitimate expenses. But the encounters often become intense and emotional and expose deeper issues and problems in the lives of the characters. One meeting turns violent. Another reveals marital problems. In one of the more beautiful scenes, Sandra begs for her job, and her coworker breaks into tears and begs forgiveness for voting against her. We see that the exchange also bolsters Sandra. She leaves this encounter with a lighter step, smiling and momentarily relieved.

This successful encounter reveals another element of Catholic social teaching: the need for the civic virtue of solidarity. St. John Paul II defined solidarity as “a firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the common good; that is to say, to the good of all and of each individual, because we are all really responsible for all.” In those who respond favorably to Sandra, we see this commitment to the human individual, who is also part of the whole. The “whole” in this situation is the business, which is also a kind of community. The workers come from disparate backgrounds but are bound by a common means of employment, through which they acquire the material goods necessary for human flourishing. So we see a business should not be some impersonal entity with profit for its sole goal. Employers should act justly to employees and vice versa. When individuals practice solidarity, the common good is bolstered and those temporal and spiritual goods that are a part of it are more easily attained. Thus we see solidarity as a remedy to this economic crisis. Practicing this virtue helps people realize that ultimately work is for man, not man for work.

The family is also a central theme in the story. Despite the dysfunctions, Sandra’s family is working to stay together. The parents attend to the needs of their children. The husband is supportive of Sandra. However, I also submit we can fault him for his lack of leadership. He pushes his wife too hard. She is clearly at a breaking point, and this weekend mission is making her more fragile. The scenario also shows the dilemma of the modern family, where two incomes are often required to live, even just above the poverty line. There are other, even darker issues here: a lingering fear of divorce, even suicide. Of course the causes of these problems cannot be reduced solely to economic factors, and the film does not attempt to do so. But it does show how this economic predicament exacerbates these problems.

Like all good art, the story shows us a slice of life without moralizing and banging us over the head. There are a number of messages we can take away from it, solidarity being a central one. This is a good film also because the story and imagination behind it are moral and realistic. That is, we see people faced with complex human decisions amid competing interests, and doing their best to make the right one. I think a good film works on the imagination this way. It educates the viewer while being a form of entertainment. Since one of the big lessons here is solidarity, and since this is an important virtue for our time, I recommend seeing this film.

✠

Image: Movie Poster