The Sights and Sounds of Christmas:

O Magnum Mysterium, composed by Morten Lauridsen

Christmas is principally a mystery of hope—of the almost but as yet unrealized. The God-child, having broken forth into his own creation, lies helplessly in a manger before the whole world. The totality of saving grace is present in his infant body, though it will remain hidden for another thirty years.

Too profound for the concreteness of human words, the Nativity lends itself to apt expression in sacred art and music. Among the most beautiful texts set to song is the O Magnum Mysterium from the ancient chant responsories of Matins for Christmas Day.

O magnum mysterium,

et admirabile sacramentum,

ut animalia viderent Dominum

natum, jacentem in praesepio.

Beata Virgo, cuius viscera

meruerunt portare

Dominum Jesum Christum.

Alleluia!

O great mystery,

and wondrous sacrament,

that animals should see the newborn Lord, lying in their manger!

Blessed is the Virgin whose womb

was worthy to bear the

Lord Jesus Christ.

Alleluia!

While commonly set in polyphony since the Renaissance days of Palestrina, the O Magnum text has experienced something of a revival since the American composer Morten Lauridsen arranged it in a much more modern style 25 years ago this Christmas.

Lauridsen’s O Magnum is so stunning because it truly achieves the purpose of sacred music (cf. Musicae Sacrae, 31-34): to bridge heaven and earth in sound and to make, if for a moment, the infinite majesty of God seem perceptible to the human mind via the ear. Lauridsen accomplishes this by simulating one of God’s primary attributes, namely his simplicity. As a text, the O Magnum Mysterium responsory is simple and direct, and Lauridsen matches this with simple and direct musical materials that give pride of place to the words. The piece thus acts as a kind of monstrance, illumining the substance of the text before the contemplative, auricular gaze of the listener.

Indeed, in bringing us to the Bethlehem stable, the words of O Magnum declare the dumbfounding humility of God: that he should stoop to assume our flesh, our contingency, our poverty—even unto a birth in a barn befitting beasts, not men—all while never ceasing to be God. The lines likewise turn our attention to the Beata Virgo, the one whose consent kick-started the New Covenant. She is beata not because of her own merits but because her viscera were found worthy to bear the Lord Jesus Christ. For it is to him and from him that all grace is ultimately credited.

Lauridsen’s setting brings all of this into sonic relief. In a great interview, he explains that those very two theological themes, God’s grace to the meek and the veneration of the Virgin Mary, frame his composition. To communicate them, he uses only inverted primary chords with a simple, chant-inspired melodic line alternating across voice parts. A persistent though discreet dissonance—a modern technique—supplies an ethereal feel that holds the attention of the listener’s ear and thus his heart. The chords repeat and adjust at the syntax of the text: the titular line, “O Magnum Mysterium,” resounds throughout like a theme, each time penetrating the listener a bit more deeply, and the insertion of a noticeable minor cadence cues us to little details, such as the Lord’s state at his birth, jacentem in praesepio (lying in a manger).

The high point of the piece, Lauridsen affirms—and the most difficult for him to compose—is its singular non-harmonic note, which accents the word “Virgo.” Lauridsen wanted to “shine a sonic spotlight” on Mary’s sorrow at the Nativity, that she foreknew the pierced heart she would so purely and innocently suffer on Calvary. Providing a quick, sharp dissonance, the G# subtly evinces that even the Nativity, in all its graced grandeur, is still a mystery tinged by sin. Though its protagonists be divine and immaculate, Christmas is not the end of the story; it, like the whole of the Christian life, directs our gaze to a cruciform climax where sin and death are vanquished. Lauridsen takes care to do this, too, concluding the piece with a soaring repetition of the great Easter anthem: “Alleluia!”

The irony of beautiful sacred music is that it cultivates interior silence precisely by means of its sound. In clearing from our hearts the noise of the world, sacred music enables us to hone in on the one for whom we are made, God, who is himself perfectly silent. The simple, arresting beauty of Lauridsen’s O Magnum Mysterium induces this divine silence in the human heart and escorts us, 2,000 years post facto, into the stillness of the Bethlehem stable. There, we behold him, awestruck at the radiance of grace.

✠

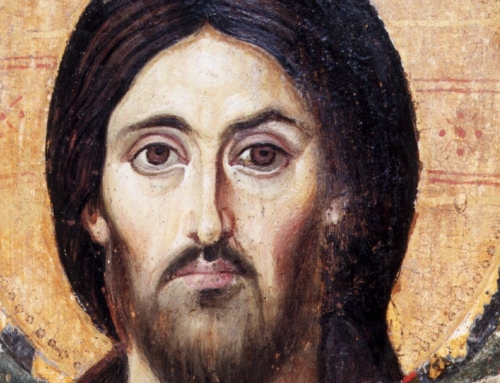

Image: Philippe de Champaigne, The Adoration of the Shepherds