“It is better to give alms than to treasure up gold. For almsgiving delivers from death, and it will purge away every sin” (Tobit 12:8-9)

Most of the Thomistic Institute’s intellectual retreats hosted here at the Dominican House of Studies end with a session of Quaestiones Quodlibetales (quodlibetal questions) in which the attendees are invited to ask the conference speakers not only about their presentations, but about anything whatsoever. In fact, this is exactly what the name itself means: the quaestio de quolibet means a question about whatever it pleases one to ask.

Scholastic disputations were quite common in the Middle Ages, and participation in them was required from the masters of theology at the University of Paris. In normal disputations, the masters drafted and arranged the questions beforehand. On the day of the disputation, the students would argue over the pre-selected topic. At some later time, the master would give his own magisterial determination. However, what made quodlibetal disputations special is that they could not be pre-planned. These quodlibetal questions would be raised a quolibet (by anyone) de quolibet (about anything). Moreover, this was all done publicly, open to those outside of the university community. Thus, they were viewed by many masters as an arduous exercise that always carried the risk of embarrassment. Moreover, unlike normal disputations, at which participation was mandatory, masters were never obliged to conduct quodlibetal disputations, and some never did.1

Because of the difficulty and possible embarrassment involved in quodlibetal disputations, they can rightly be viewed as a penitential exercise. Everyone knew of the “taxing nature” of the Quodlibetal disputes.2 Perhaps then it is no coincidence that quodlibetal disputations were held only during Advent and Lent, traditional penitential seasons. For this reason, one translator of the quodlibetal questions of Aquinas has likened quodlibets to a form of intellectual almsgiving. Thomas Aquinas, for his part, excelled at this almsgiving. Of all the quodlibetal questions available to us today, those of Thomas are in a class of their own: they are the only extant quodlibetal questions to have been authored by a canonized saint.3

Because the questions could be posed by anyone and about anything, it was very common to have questions of a practical nature concerning the care of souls.4 These questions addressed the difficult situations confronted by Christians in their day-to-day lives. In such disputes, Thomas put himself at the service of his fellow clerics and those studying to be clerics in order to answer the questions that they did not have the time or ability to determine for themselves. In conducting disputed questions, Thomas ceased to pursue his own projects (though these projects were themselves aimed at the salvation of souls) in order to answer the pressing questions of the day. Later, the ordinary Christian faithful would benefit from Thomas’s contemplation when his clerical students returned to their pastoral roles.

The utility of Saint Thomas’s teaching for clerics and the faithful alike is made clear by their widespread circulation in pastoral guides for priests. The “pastoral teaching” of the quodlibets was “known and quoted all over Europe from about 1300, finding its way into all sorts of small pastoral manuals.”5 This fact reminds us that St. Thomas was not an ivory tower intellectual. His study was not for the sake of personal amusement and gratification. The sacred study of St. Thomas was for God and for his neighbor, and he desired that as many as possible should benefit from his labor. He was at the service of all, though the fruits of his contemplation often reached the ordinary faithful through other intermediaries, namely his students. Jacques Maritain put it very well when he said, “All his knowledge was employed for the service of others. His immense work was conducted not according to his choice, but according to the commands of Providence.”6

Following the example of Thomas, in addition to performing corporal works of mercy, we should not neglect the spiritual works of mercy. Like St. Thomas, we must counsel the doubtful, instruct the ignorant, and admonish the sinner. If we wish to be prepared to fulfill this calling to perform spiritual works of mercy, we ought to heed the advice of Pope Pius XI and “Go to Thomas.” Still, if we are tempted to think that we can’t learn from a master as brilliant as Thomas or if we struggle to understand his thought, we need not despair. Today, as in the middle ages, the fruits of Thomas’s contemplation are able to reach us through pastors and mediators who make this fruit a little more accessible.

✠

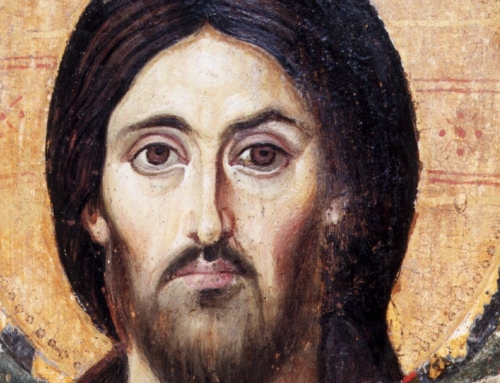

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)

- Turner Nevitt and Brian Davies, eds., Thomas Aquinas’s Quodlibetal Questions (Oxford University Press, 2019), xxiv–xxv. ↩︎

- Wippel, “Quodlibetal Questions, Chiefly in Theology Faculties,” 171. ↩︎

- Kevin White, “The Quodlibeta of Thomas Aquinas in the Context of His Work,” in Theological Quodlibeta in the Middle Ages (Brill, 2006), 1:119. ↩︎

- “A large proportion of the students in the theological faculties of Paris, Oxford, and elsewhere, was engaged in or destined for pastoral care at one level or another.” Leonard E. Boyle, “The Quodlibets of St. Thomas and Pastoral Care,” The Thomist: A Speculative Quarterly Review 38, no. 2 (1974): 243. ↩︎

- Boyle, “The Quodlibets of St. Thomas and Pastoral Care,” 252. ↩︎

- Jacques Maritain, St. Thomas Aquinas (Meridian Books, 1958), 39. ↩︎