On the night of September 13, 1814, as Fort McHenry in Baltimore was under attack during the War of 1812, Francis Scott Key observed a small, tattered American flag flying in the midst of the fiery siege. The uncertainty of the battle made him wonder if the “star-spangled banner” would still be flying by morning. This scene before him would inspire a poem, which later set to music would become our national anthem. When “the dawn’s early light” came over Maryland, another American flag, larger and more majestic than the one from the night before, was flying strong. It was the morning of the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross.

The flying or displaying of flags can have several meanings (even leading to its own field of study, vexillology). For many, a flag is symbolic of an entire nation or people. American practices of saluting the flag and standing for the playing of the national anthem express respect not merely for the symbol of the flag, but for the country which it signifies. This symbolism had added significance for Key, who upon seeing the American flag flying at daybreak knew that the republic had been victorious. Earlier uses of flags, dating back to antiquity, identify them not so much as symbols of nations but of individual persons, such as kings or military leaders. Such flags were known as standards (vexilla in Latin), and would often be carried into battle, signifying the power of the ruler with whom the standard was associated.

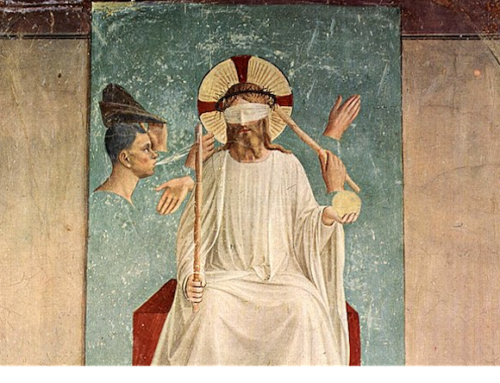

Christians would eventually see this use of the standard as a way of understanding the Cross. Bishop Venantius Fortunatus captured such imagery in his sixth century hymn, Vexilla Regis, which was first used in processions during Holy Week. Fortunatus illustrates the Cross as Christ’s standard, one belonging to a king as he marches into battle:

The royal banners forward go,

The cross shines forth in mystic glow;

On which our Maker, to redeem,

Did hang incarnate from the beam.

Christ the King mounted the wood of the Cross on Calvary, defeating sin and death, and rose victorious on the third day. While the Cross initially seemed to be a sign of defeat and humiliation, Jesus made it a sign of triumph. For his wayfaring Church on earth, the Cross is the standard of her king, which she carries confidently into spiritual battle against the enemy. Tomorrow’s Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross reminds Christians not to be ashamed of the Cross, for in it lies the salvation won for us by Christ.

This message of redemption must impel every Christian to carry out the Church’s evangelical mission. Even in the midst of attack, persecution, misunderstanding, and ridicule, Christians are called to “preach Christ crucified,” even if it should be “a stumbling block” to the world around us (1 Cor 1:23). We march forward, carrying our standard—the Cross of Christ, the “lovely and refulgent Tree, adorned with purpled majesty.”

When bombarded by the everyday struggles, dangers, and temptations of life, one can easily fear that hope is lost. When such difficulties are ongoing, we may question if Christ is really there to raise us up. Yet the psalmist reminds us that we need “not fear the terror of the night, nor the arrow that flies by day” (Ps 91:5), for in Christ and his Cross lies our spes unica—our only hope. After the dark night of battle, we will greet the dawn to find the Cross, standing victorious in the light of the Risen Christ.

✠

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)