One Saturday in 1884, twenty-eight-year-old Matt Talbot stood outside O’Meary’s pub in Dublin, Ireland. He was low on cash. Workers streamed by him, men with whom he had often labored, and he waited for one of them to invite him in for a drink. Work hard; drink hard—this had been his rhythm of life since he was a young man. All his money went to pubs. And when he was out of work and had no money, he found ways to get it—selling his shoes or clothes, or, once, stealing a fiddle from a blind street performer and pawning it. But this Saturday no one stopped to invite him in.

Something inspired Matt to leave his post by the pub door that day and return home to tell his mother that he would make the pledge—a promise to give up alcohol for three months. He went to a nearby seminary for confession. Three months later he renewed the pledge and never had a drink again. After over a decade as an obstinate drunk, Matt dropped the habit.

He lived his remaining years in quiet, hidden penance, growing in the spiritual life through prayer, the sacraments, and acts of charity. His life was so quiet, in fact, that he probably would be forgotten today except that when he died on the way to church on June 7, 1925, he was discovered to be wearing chains of devotion and penance under his clothes. Though his struggle from alcoholism to asceticism was mostly unknown to others, after his death Matt became recognized by the universal Church as a holy man, a role model and inspiration to those struggling with addiction.

I learned about Matt Talbot’s story this summer, which I have spent in Baltimore working at a soup kitchen with the poor and homeless. This city has been called the U.S. Heroin Capital. Every day I see people stooped over, swaying, stumbling to their seats, unaware of the ground under their feet, and falling asleep in their food. In Baltimore, an estimated one out of every ten citizens is addicted to opioids. And the city is only one hotspot in an epidemic that killed fifty-two thousand Americans in 2015.

Lives consumed by substance abuse make particularly obvious the misery of sin. Sin leads to more sin, and a life of sin leads to destitution and a profound unhappiness on the edge of despair. Those of us who personally know people being destroyed by addiction may begin to wonder how, or if, such darkness can be overcome. But Matt Talbot’s life shines a light into this darkness. He is reported to have said, “Never think harshly of a person because of the drink. It’s easier to get out of hell than to give up the drink. For me it was only possible with the help of God and our Blessed Mother.”

Matt only could address his perverted love of alcohol when he encountered a greater love—the love of the Father who welcomes home a wayward, profligate son; the love of the King who searches out the neglected to come celebrate his son’s wedding feast; the love of the shepherd who seeks the one wandering lamb, who prays that none may be lost. Matt Talbot’s story shows that this love is real and efficacious, able to free us from even the strongest of sinful bonds.

✠

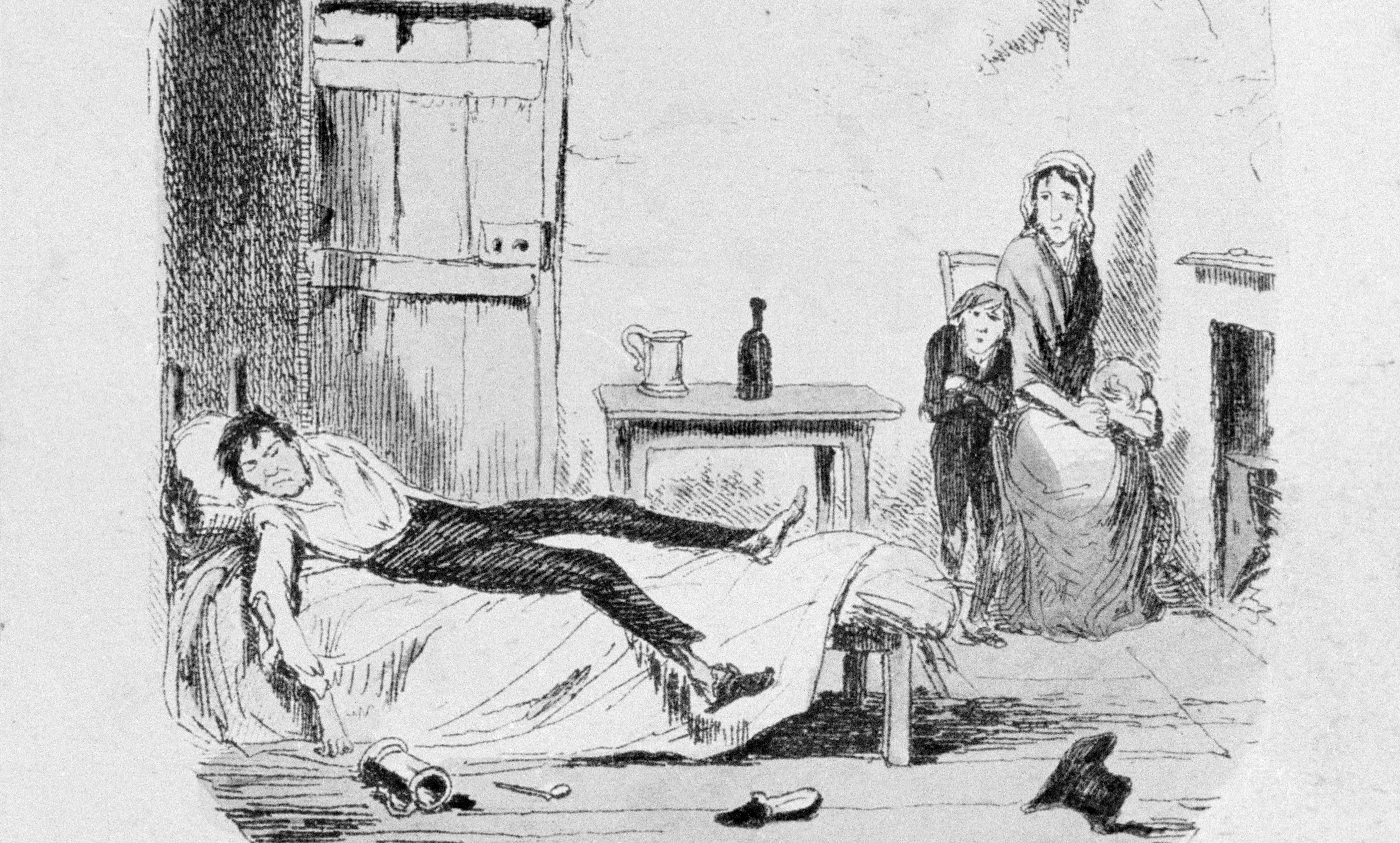

Image: George Cruikshank, The Drunkard’s Home