(Spoilers!)

A number of characters from the most recent installment of Star Wars struck me as exemplifying a real source of struggle for many people today: a desire to break from the past. Kylo Ren voices this leitmotif of the film: “Let the past die! Kill it if you have to. It is the only way to become what you were meant to be.” Luke Skywalker too has forsaken the past. He takes his old light-saber, brought to him by the youthful and eager Rey, and callously chucks it over his shoulder. Later in the movie, we discover something more startling—he has cut himself off completely from the Force. He even attempts to burn the most sacred books of the religion he has abandoned.

Whether one agrees or disagrees with the direction that J.J. Abrams and Rian Johnson, along with Disney, have taken the Star Wars narrative, this fictional story reflects today’s real-life struggles concerning one’s relationship to the past and self-identity. Some say, with Kylo Ren, that who I will be—who I was meant to be even—requires abandoning the past, forsaking my roots, and building a completely new future.

Consider Kylo’s words in light of Pope Francis’s: “Those who would break all ties with the past will surely find it difficult to build stable relationships and to realize that reality is bigger than they are” (Amoris Laetitia 192). How often do we see children who, like the prodigal son, intentionally seek to get far away from home so they can build their own life—so they can “become who they were meant to be.” Becoming independent adults is a good and healthy thing, but we cannot discover the true way alone. Pope Francis goes on to identify “the lack of historical memory” as a “serious shortcoming in our society” (AL 193). We are often rightly encouraged to dream about the future, but do we take time to know our family history? Or our country’s history? Or our religious history? Perhaps our fifth cousin twice removed, or a saint from the 6th century, could help us to discover where we come from and who we really are.

Holy Scripture offers us an example of collective memory giving meaning to our lives.

“Later on, when your son asks you what these ordinances, statutes and decrees mean which the LORD, our God, has enjoined on you, you shall say to your son, ‘We were once slaves of Pharaoh in Egypt, but the LORD brought us out of Egypt with his strong hand and wrought before our eyes signs and wonders” (Dt 6:20-22).

Here we see that Israel’s identity is dramatically revealed in its family history. The Christian shares this story and builds on it. He knows that “we were once slaves,” but now, in this present age—through a real history climaxing with the full revelation of Jesus Christ—the baptized “are children of God” (Rom 8:16). This glorious identity is bound to this marvelous history. The two are inseparable.

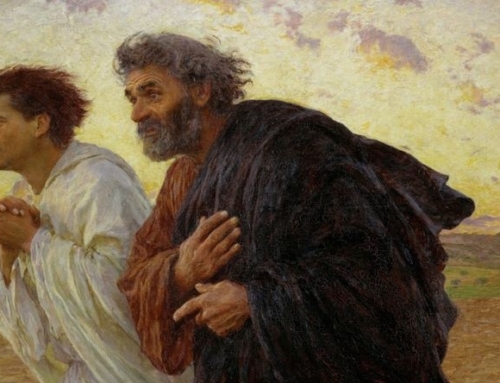

It is moving at the end of the Star Wars film when Luke finally reconnects to the Force after those close to him remind him of the past and point him forward. Our true selves are also bound up in our history, with both its good and bad chapters. Let us not close our hearts when a member of the family reminds us of our story—especially as it relates to our heavenly family and our ultimate vocation. And let us not fail to be instruments in keeping that collective history alive, for it is in this that we discover who we are.

✠

Photo of Skellig Michael by user Jibi44 (CC BY 2.5)