If today English-speakers still hear about “the feast of Stephen,” we can probably thank one man: John Mason Neale.This nineteenth-century English churchman and poet once chanced upon the felicitous rhyming of the name “Stephen” and the adjective “even.” Thus, we presume, was born “Good King Wenceslas,” the lively Christmas carol. Thus also was commemorated the liturgical feast of Saint Stephen, whom we celebrate today, the day after Christmas (For an excellent Dominicana post about the carol, see here).

Why do Roman Catholics celebrate Stephen today, the day after Christmas? It seems to make no sense at all.

It’s the day after Christmas. The evergreens are still green, and the leftovers are still around. More importantly, the joyous Gloria of the angels and the murmured adoration of the shepherds still echo in our ears. We want to think about peace to people of good will.

Instead, the Church presents us with the story of Stephen. As a deacon, his ministry was brought to a sudden and violent end. His promising preaching career, which began with “great wonders and signs among the people” (Acts 6:8), came to an abrupt halt. His enemies shout down Stephen’s words about Jesus, drag him out of Jerusalem, and stone him to death.

Saint Stephen has the honor of being the first martyr. He suffered death to witness to Jesus Christ. Martyrdom is more glorious than any preaching, and it is certainly worth celebrating. But the question remains: Why celebrate the first martyr the day after Christmas? Doesn’t it interrupt the warmth and cheerfulness of the feast?

I would like to suggest that the Church proclaims the death of St. Stephen today precisely so that we understand Christmas. Saint Paul, who stood watching as the protomartyr gave his life for Christ, tells us this about Christmas: “This saying is trustworthy and deserves full acceptance: Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners” (1 Tim 1:15). He would save sinners through his Precious Blood. He would save Paul through this blood. He would save us through this blood. “God loved us and sent his Son as expiation for our sins” (1 John 4:10).

Christ was born to save. The death of Stephen, which parallels closely the death of Christ, echoes and shows forth the deepest “reason for the season.” The coming of Jesus is the reason for Christmas, and our salvation is the reason for his coming. For us men and for our salvation he came down from heaven (Nicene Creed).

God did not become man simply for the glory of elevating created nature so that we could say, as we can: “This man, Jesus, is God.” Nor did he become man simply to teach us, and to reveal to us the inner life of the Trinity. He did these things, certainly: but he did so as our Savior.

The Word became flesh to become the divine answer to the ugliness of sin—of original sin, and of every one of our personal sins. The Word came to heal us and, in the mystery of God’s providence, this means that he came to suffer and to die: to offer his life, once and for all, as a ransom for sinners. Stephen and every martyr after him joined their self-offering to this perfect sacrifice of love.

This Christmas, we do not only celebrate the good things of family and home. We do not even only celebrate the fact that God became man. We rejoice that, out of his love for us, this child who is God will give his life for the salvation of the world.

Stephen knew the peace of Christmas. He knew it well enough to pray, as he died: “Lord Jesus, receive my spirit” and “Lord, do not hold this sin against them” (Acts 7:59-60). On this feast of Stephen, we pray that we too may be joined to the redemptive love of the Word made flesh. May we die with Christ, and so rise with him, in the peace of our King who was born to save us.

✠

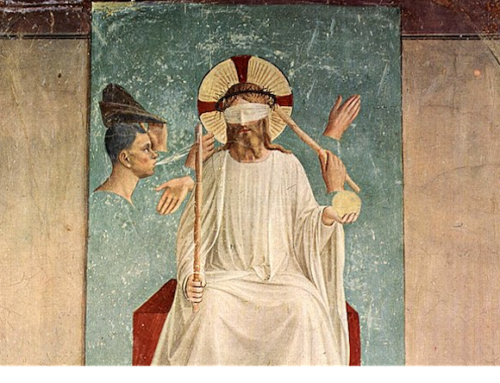

Image: Juan de Juanes, Entierro de San Esteban