It is a truism that God can draw good out of evil. Perhaps more surprising is the truth that God sometimes gives marvelous growth to the most important virtues through one’s struggle with an apparently unrelated, and quite pernicious, vice.

As to pernicious vices, I’m thinking in particular of the scourge of Internet pornography use among Americans, especially American men. Even secular sources, who fail to see the use of pornography as an intrinsic evil, have sounded concerned notes: “Online pornography use is on the rise, with a potential for addiction considering the ‘triple A’ influence (accessibility, affordability, anonymity).” Priests have long known the destructiveness of this vice. The U.S. Bishops give this sacerdotal perspective in their 2015 pastoral letter, “Create in Me A Clean Heart”:

In the confessional and in our daily ministry and work with families, we have seen the corrosive damage caused by pornography—children whose innocence is stolen; men and women who feel great guilt and shame for viewing pornography occasionally or habitually; spouses who feel betrayed and traumatized; and men, women and children exploited by the pornography industry. While the production and use of pornography has always been a problem, in recent years its impact has grown exponentially, in large part due to the Internet and mobile technology.

The sins attached to pornography blind and bind people—with bonds of misguided desire, overwhelming shame, isolated loneliness, and profound guilt—and prove beyond doubt the veracity of Christ’s words, “everyone who commits sin is a slave of sin” (John 8:34).

Pornography is bad enough. But what if the fact that not one, not a few, but many, many American men have fallen under the siren song of pornography and cannot seem to extricate themselves reveals a deeper, more insidious sin? And what if that sin has marked our country and our history in more ways than one? I’m speaking of a form of self-reliance that says, “I am what I make myself to be.” Pope Leo XIII noticed this about us—our American “go-getterism” can sometimes become “an overestimation of natural virtue,” as if, on our own strength, we could do the good we desire. In short, we are tempted to the sin of Pelagianism—a subtle denial of original sin that convinces us that if we are to be saved, we must be the ones to do the saving. And the recurring cycle of resistance, capitulation, and shame that afflicts users of pornography smacks of an attempt to live Pelagianism and shows its impossibility at the same time.

So perhaps to confront the pandemic of pornography in our country we must first squarely face a sort of national Pelagianism. John Cassian, that saintly ancient curator and conveyor of monastic wisdom, described what happens when we start to let go of Pelagianism in matters of purity:

To begin not to hope for it by one’s own laborious efforts is a clear sign that purity is already near. For if someone has truly grasped the force of the verse: “Unless the Lord has built the house, those who are building it have labored in vain” (Ps 127:1), it follows that he should not glory in the deserts of his purity, since he realizes that he has obtained it not by his own toil but by the Lord’s mercy. (Conference XII.15.3)

Cassian’s words make sense (and here he shows none of the semi-Pelagianism of which he is sometimes accused!): What value is purity if we are puffed up with pride, seeing ourselves as the author of our own goodness? God never wants us to sin, but he can use our impurity to reveal to us his salvation. He shows us that he has already won the battle against impurity, once for all, on the cross, and asks us to cling to him so as to share in his victory. In the words of St. Augustine, “God created us without us: but he did not will to save us without us.” Perhaps the battle will be long, but victory is assured.

God can indeed draw good from evil—he can draw profound humility and hope from the struggle with sensual vice. The struggle is not without purpose; nor are moments of defeat cause for despair.

Humility and hope are the seeds of victory, not only over the vices of the flesh, but over that deadly pride marking every desire for salvation in which God’s role is anything other than primary.

✠

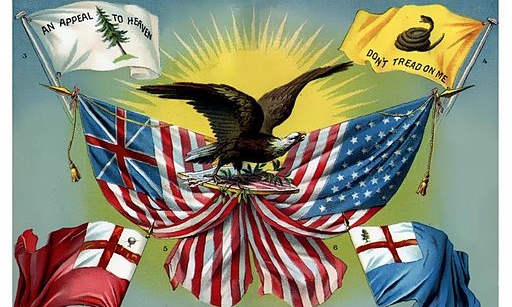

Image: History of U.S. Flags, Wikimedia Commons