When early Greek mathematician Archimedes discovered that the water rising in his bathtub equaled the volume of his body dipping into it, the sheer feeling of discovery compelled him to exclaim “Eureka!”ーI have found it! Ironically, his discovery drove him to preach his wisdom zealously, rather like a fool, naked through the streets of Syracuse. Discovery, evidently, excites!

Saint Albert the Great, Doctor universalis of the Church, was a model scientist, making major discoveries in astronomy, geology, music, and many other subjects. He writes in his De Mineralibus, “it is [the task] of natural science not simply to accept what we are told but to inquire into the causes of natural things” (II, ii, 1). For St. Albert, discovery looks beyond things at face value, turning to their causes. Discovery should lead us then, as it led St. Albert, to recognize the ordered whole of the cosmos through its causes.

Saint Albert may have said to himself “Eureka!” at his desk or out in the field, discovering the ordered whole through the categorization of minerals or animals. As exciting as minerals were, St. Albert’s greatest discovery was knowledge of God, the first and uncaused cause of the ordered whole. A Dominican friar, St. Albert’s whole life was oriented toward contemplating the things of God. Thomas Schwertner describes St. Albert as one discovering Christ on a journey:

But this belated disciple of the Unseen Master, walking with Him daily on the way to Emmaus for the breaking of the bread, “felt his heart burning within him,” and so ran to the city to tell those busy about many things that he “had seen the Lord.” (Saint Albert the Great, 156)

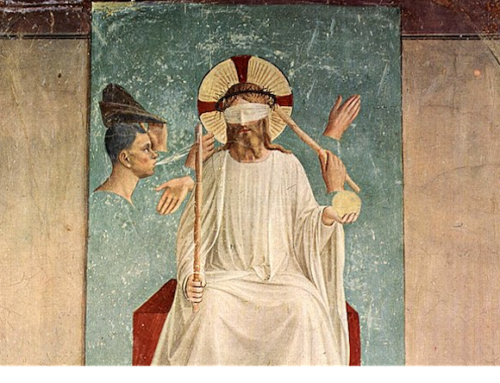

The scriptural reference to Emmaus, where two disciples encounter the risen Jesus, calls to mind the painting of the scene by Baroque painter Caravaggio. He captures the exact moment of “Eureka!”ーone disciple leaps out of his chair, while the other gestures his arms out wideーa moment of shock, awe, and discovery. Their discovery: the Lord is truly risen.

The story did not end there. The disciples “rose that same hour,” and “told what had happened on the road, and how he was known to them in the breaking of the bread” (Luke 24:33–35). The risen Christ granted the disciples wisdom in his presence, and this wisdom paradoxically drove them to preach zealously like “fools for Christ’s sake” (1 Cor 4:10).

If Archimedes thought measurement of volume was worth preaching like a fool, Christians surely should think the same regarding Jesus Christ.

Saint Albert certainly expresses this in his works: preaching on natural things with God as creator, and on supernatural things with God as savior. Indeed, he lives out what his student, Saint Thomas Aquinas, put into words: “[It is] better to give to others the fruits of one’s contemplation than merely to contemplate” (Summa Theologiae, II-II, q. 188, a. 6).

If we wish to share contemplation’s fruits, how exactly can we contemplate? Just as the disciples saw Christ in “the breaking of the bread,” we can contemplate our Lord most perfectly in the Eucharist. The disciples’ eyes were opened by the light of faith, and likewise, our minds are illumined by faith before the Eucharist where the true but hidden presence of our Lord is found. As a priest, St. Albert would have made this faith-filled discovery daily at the Mass. Like St. Albert and the disciples, may we look to the Eucharist and preach “Eureka!”ーwe have found him.

✠

Image: Caravaggio, Supper at Emmaus