“Class, do not be drawn in by the myth of closure. That our life has finality is a complete lie.”

This strange aside from my twelfth-grade English teacher turned all my dreams for life into embarrassments.

And as my life has gone on, it seems he has been proven right. Perhaps we all can attest to this. Years have passed since you spoke to the college friend you swore you would know forever. Love goes unrequited, and hearts are left broken. Those big plans had to be set aside. That conversation that needed to happen just . . . never did. Can we seriously say that all the loose ends will be tied together in a pretty little bow before our last breath? Is there such a thing as closure?

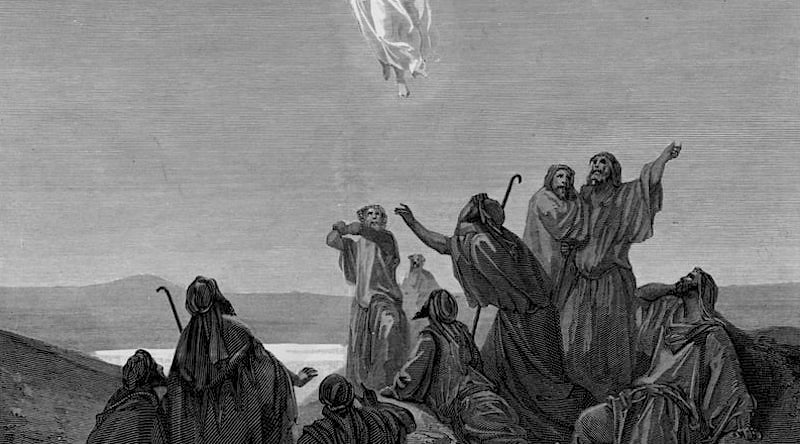

As the Apostles gazed upon Jesus—their friend and fulfillment of their hope—ascending into heaven, they probably thought of all they left unsaid. But instead of closure, they were given a mission: “You shall be my witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria and to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8). The Apostles’ friendship with Jesus seemed over. Yet they were expected to hold onto it, and more than this, to share it with the whole world.

Tomorrow, nine Dominican friars will submit to this mission, and be ordained priests of Jesus Christ.

To the world, the priest might be seen as the man-without-closure par excellence. He never found the right career or hobby. His heart was broken, or worse, was never opened so as to be broken. He is a perpetual bachelor and loner. He is an unfinished man.

But from heaven, Jesus sees nothing less than a man who has chosen the path of finality and closure—for his own life and the life of the world.

You see, when things have been left unfinished and unsaid, we get that awful feeling in our bones, as if the world is crashing down around us. But these things—our relationships and careers—will pass away. If life often feels like sand passing through our fingers, that’s because it is. But relationship with Christ is for all eternity. Here on Earth, it is through the priest that we have such a relationship.

This relationship comes first for the priest himself. The priest sacrifices passing things in favor of a special relationship with the crucified Jesus. But this does not make him passive. Rather, like his Lord, he shows himself a man who has decided with vigor to live a cruciform life (ST III, q. 47, a. 1). And this decision is not for a few years or even until a comfortable retirement, but forever:

The Lord has sworn

and will not change his mind,

“You are a priest forever

after the order of Melchizedek.” (Ps 110:4)

And this relationship is not just for the priest, but for the sanctification of the world. The hands of the apostles, which shook with terror when the Lord ascended, were the same hands which passed down the priesthood, to be brought to this generation. Now, with each ordination, human hands manifest that Christ is with us. Through these hands, bodies and souls are filled with the sustaining power of the Eucharist and the chains of sin are broken in confession. On our deathbed, we may not find the human closure of which my English teacher spoke. But the priest can bring us eternal closure in the beatitude that follows.

The priest himself may be unfinished. But in truth, all of us are unfinished, and in the passing things of our personal and professional lives, we will remain so. But the priest gives to us the only closure we truly need: Jesus Christ. From the heart of the lowly priest, the words of Jesus boldly sound: “Lo, I am with you always, to the close of the age” (Matt 28:20).

✠

Image: Gustave Doré, The Ascension