“Jerusalem, Jerusalem.” Eighty-five years ago today, Marie-Joseph Lagrange passed into eternity with these words on his lips. The Dominican friar who did perhaps the most of any Catholic in the twentieth century to further biblical studies died March 10, 1938 in his native France. Though a Frenchman by birth, his last words reveal where his heart truly lay, and where his body now rests.

Albert Lagrange was born at Bourg-en-Bresse in southwestern France on March 7, 1855, the feast of St. Thomas Aquinas. He entered the Order of Preachers in 1879 in the Province of Toulouse, receiving the name Marie-Joseph, and was ordained a priest in 1883. The next several years saw him study Oriental languages and Scripture until 1889, when he was given a shock by his superiors: he would be sent to Jerusalem to open a school for the study of the Bible. On March 10 of the following year, he arrived in the Holy City, finding stark conditions: the Dominican priory was housed in the former town slaughterhouse, there was no faculty for a school, and the library had no books.

But providence was with Lagrange. In short order, the friars he drew to the school established themselves as masters in their respective fields of technical sciences, from geography to philology, from epigraphy to exegesis. An academically rigorous periodical, the Revue Biblique, was founded. The school, the École Biblique, was quickly becoming one of the most notable Catholic centers of biblical studies.

However, when Pope Leo XIII, a champion of robust biblical study, died in 1903, darker days loomed for the friar increasingly known to the Catholic world simply as Père Lagrange. The next ten years were filled with arrested projects, anxious correspondence between Jerusalem and Rome, and unfortunate criticism leveled against Lagrange and his pupils. Many Catholic scholars were wary of new ideas, stemming from concern with the infiltration of the Church by Modernism. This ultra-rationalist heresy threatened all foundations of the Faith, from philosophy to theology to Sacred Scripture. Catholic scholars battened down the hatches, especially when it came to interpretation of the Word of God.

The foresight of Père Lagrange lay in his assessment of the problem in Catholic biblical science. Père Lagrange was fiercely devoted to the theology of St. Thomas, but he knew that the war against Scripture was not being waged by the Church’s enemies with the weapons of metaphysics or classical theological distinctions. Rather, it was with those of history, archaeology, languages, and the like—an armory unfamiliar or even suspect to many Catholic scholars. Père Lagrange pressed on. The storms of Modernism would subside, and calmer times, Lagrange knew, would find him and his friars ever more diligently, faithfully, and fruitfully laboring in Palestine for the sake of God’s Holy Word. Those calmer days came and proved him right. The years, and accomplishments, rolled on, until ill health bade him permanently depart Jerusalem for France in 1935.

Père Lagrange was a religious of immense wisdom. He was labeled backwardly obedient to the Church by secular critics, and a reckless progressive by some within the Church. But he knew that, when scholarship came to the Faith, it’s never a matter of inhibition or innovation, but of Rome or renegade. When he received word that his commentaries on the Old Testament were not fit to be published, he turned obediently to the New, paying little thought to his own effort expended. He had been sent to the Holy Land to live and breathe the Bible for the sake of the Church. Jerusalem had been the testing ground for his belief that, by studying Scripture alongside its physical data, the Word of God could be proclaimed more clearly in medio ecclesiae. He was right.

In 1912, Père Lagrange wrote to Pope Pius X in filial anguish, “My first thought was, and my last thought will be, always to submit myself heart and soul to the orders of the Vicar of Jesus Christ.” March 10, 1938 would not find Père Lagrange anything but a faithful son of the Church. He had penned 1,786 articles, books, reviews, and commentaries—a noble feat by any academic standards. But it was a tender love for the living, breathing Word of God that ensured the hand that held that pen should never forget its direction and purpose: “If I forget you, Jerusalem, let my right hand wither!” (Ps 137:5).

✠

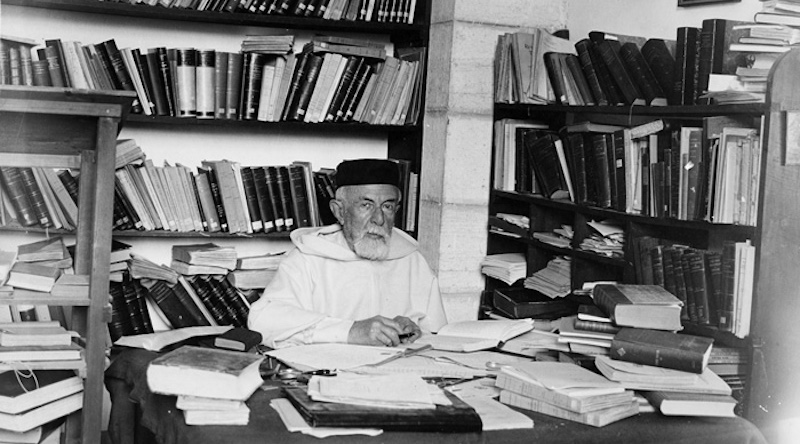

Image: P. Lagrange at his office, St. Maximin (from Dominican Province of Toulouse)