This is part of a series on American Catholic authors. Read the series introduction here.

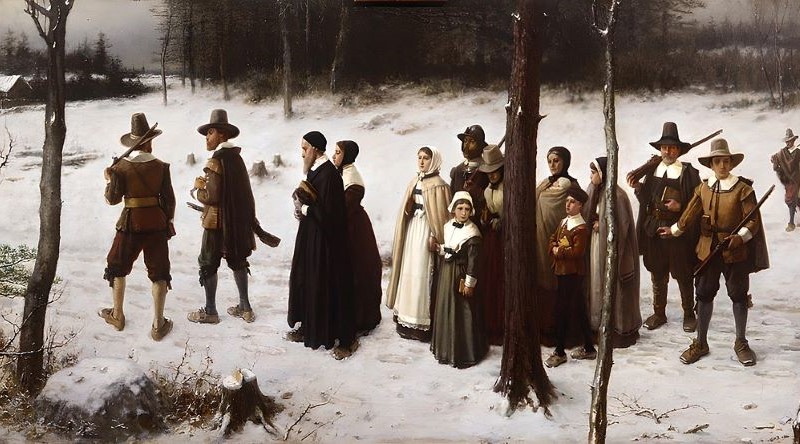

Americans have always looked for a home. The Pilgrims, the pioneers, and the homesteaders all wanted a place to call their own. Orestes Brownson was no different.

Born in Stockbridge, Vermont, in 1803, Orestes Augustus Brownson entered into a world that was anything but stable. Due to his father’s early death and his family’s poverty, Brownson spent his childhood in the households of various elderly couples kind enough to take a poor boy in. This separation from his family and lack of early friends combined to create a reflective boy, and a voracious reader besides: “I felt neither hunger or thirst, and no want of sleep; my book was my meat and drink, home and raiment, friend and guardian, father and mother.”

Loneliness is a painful reality, however, and Brownson would later confess that it was the lack of an earthly father that sparked such an ardent search for the heavenly one. Raised under the roofs of strict Congregationalists, Brownson understood Calvinism from a young age. He was reading Jonathan Edwards’ History of the Work of Redemption when others were still learning the alphabet. Young Brownson went so far as to get into a public debate with two older gentlemen concerning predestination—at the age of nine. But any stable life in Congregationalism was not possible. Eventually, he was baptized in a Presbyterian church. Then he became a Universalist preacher, traveling and writing with fierce rapidity. He finally settled in Boston in the mid-1830s, having embraced a middle-line Unitarianism.

Brownson’s writing can’t be understood without understanding those who surrounded him: the Transcendentalists. A highly romanticized set, these New England thinkers, writers, educators, and reformers put American literature on the map in a way no other movement had. Brownson was at the heart of it all.

But from the start, Brownson looked at the world differently from the other Transcendentalists. When it came to the nature and purpose of writing, he worried about those who tried to sequester literature as an entity in itself—mere poetics. He thought otherwise.

Literature, in our sense of the term, is composed of works which instruct us in that which it is necessary for us to know in order to discharge, or the better to discharge, our duties as moral, religious, and social beings. (“American Literature,” Brownson’s Quarterly Review, 1847)

With this view, Brownson went against the grain of his friends, insisting that art was meant to serve a higher purpose.

John Henry Newman converted in an atmosphere in which those around him were looking for the Church of antiquity. Brownson converted in a very different environment. His intellectual friends vowed their search for a new universe, a new, luminous humanity. Thoreau was at Walden Pond. Emerson was poring over the Bhagavad Gita. Other Transcendentalists like Hawthorne and Fuller were occupied at Brook Farm, building a utopia in the woods which would be a beacon of progress for a new society (it failed in 1847 after just six years).

Brownson would convert to the Catholic Faith in 1844 (a year before Newman, by the way). It struck his friends as discordant, but probably temporary; he who had traversed the whole field of Protestant confessions would soon tire of this Roman novelty. But it was no novelty. The faith of the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church struck Brownson like a gong, echoing all the way back to that precocious child in the woods with his King James, desirous of a God that made the world make sense—one that provided a sure and loving home.

As the Roman Catholic Church is clearly the church of history, the only church that can have the slightest historical claim to be regarded as the body of Christ, it is to her I must go, and her teachings, as given through her pastors, that I must accept as authoritative for natural reason. It was, no doubt, unpleasant to take such a step, but to be eternally damned would, after all, be a great deal unpleasanter. (The Convert: Or Leaves from My Experience, ch. 18)

Brownson set his pen to paper with new vigor, and wouldn’t put it down for thirty years.

His bibliography is eclectic, to say the least. The loud, rough man from Vermont spoke his mind plainly, resulting in Brownson’s Quarterly Review, a periodical edited by Brownson in which most of the articles were by Brownson himself. He railed against European Catholics’ apathy for abolition. He defended the logic of papal authority. He applauded the Immaculate Conception. The titles of his essays show his great desire to see all that was good about American life and values gathered up and laid at the feet of Christ and his Church. Besides what is found in his Review, Brownson’s defense of Catholicism’s harmony with American life culminated in his book, The American Republic. Published in 1865, it defended the Constitution, demonstrating the much more fundamental “unwritten constitution” that undergirded America, making her a land ripe for freedom, flourishing, and faith.

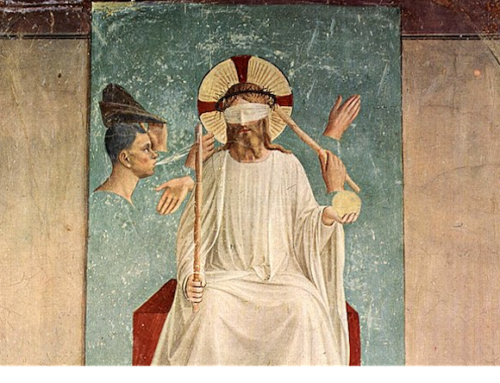

The Spirit-Rapper (1854), Brownson’s only novel, aims to explain his general worry that American Protestants, especially the Transcendentalists, did not appreciate the full weight of the supernatural. Spiritism, animal magnetism, and hypnotism were dabbled in carelessly for parlor tricks, while, at the same time, Hawthorne was penning his mocking tales of the Puritans. The novel also reveals Brownson’s veneration for his own land and literary heritage. Yes, Brownson was an American. But, like every American, he called a more particular place home. Now a Catholic, he saw it as his mission to bring his fellow New Englanders home to Rome, bringing with them all their troubled and confused past: the Mayflower, the witch trials, Puritanism, Old and New Lights—in short, the spiritual saga of every “quaint” Yankee village and town.

In the end, Brownson had certainly been gifted with a good home. The bishops of the Council of Baltimore had hailed him as America’s “intrepid advocate” for the faith. Britain’s Lord Acton confessed, “Intellectually, no American I have met comes near him.” To the end a tireless defender of Catholicism in America, our great convert would die by happy accident on Easter Sunday in the centennial year, April 17, 1876. A fitting finale for a writer of wit, zeal, and faith.

✠

Image: George Henry Boughton, Pilgrims Going To Church