2023 Summer Reading Recommendations:

The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord by Anthony Esolen

The human heart desires to sing. Enlivened by God, it seeks, at its most basic, to make a worthy return to the Lord in songs of praise and thanksgiving. Language can be beautiful. Order is peaceful and pleasing. The combination of the two—ordered language—gives man the stuff with which to fill his lungs. Down through the ages, man’s music has always begun with the simple words themselves. I am referring, of course, to poetry.

Poetry is dear to God. Scripture abounds with it. The Fathers of the Church and the early martyrs composed haunting verses which we still sing as hymns today. In his magnum opus, the Divine Comedy, Dante Alighieri tells the story of his journey through hell, purgatory, and heaven, all in the form of a grand poem. Although Dante encounters many songs and beautiful words while traveling through purgatory and heaven, it is no oversight on his part that hell includes no music. There, there are only sighs and cries, and all poetry is a dissonant, twisted mockery of sweeter songs. Music comes with the light. Poetry is dear to God.

A great poet of our own age, Anthony Esolen—himself a devotee of the Florentine—presents us with a wealth of words in The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord. This collection of original poems is the author’s plea to readers to remember what has been forgotten: how to sing. I am not talking about joining a choir. Think of your grandfather, who might still remember from his school days the opening lines of Homer’s Iliad (and in Greek at that). Or perhaps grandma can still rattle off a sizable portion of “Paul Revere’s Ride” when those famous words of Longfellow begin. When was the last time something you read lodged in your soul? You are not alone if you are scratching your head to remember. We read thousands of words every day, but have somehow demoted language to the status of a servant, made to be direct, economical, and, at worst, vulgar.

Esolen’s inspiring introduction serves as a kind of manifesto for the disappointed modern man, who finds himself in a culture which gluts his every sense yet leaves him starved of the lasting and the beautiful: “If song is for everyone, and poetry is the most exalted form of song, then poetry too is for everyone” (The Hundredfold, 9). Esolen aims to remind the reader that poetry needn’t be as ugly as the brutalist college library you see downtown every day. It should be, nay, it “must be what can enter the mind forever, and be gotten by the heart, because like music it enters the deepest chambers of the human person” (The Hundredfold, 10). Don’t believe me? “Listen, my children, and you shall hear…” I bet grandma can provide the rest. Can you?

Dr. Esolen provides us with one hundred poems, all drawing in some way from Scripture—something else we have forgotten from our heritage—laid out in a thoughtful, careful way. Perhaps you’ve never really sat down with a poem. Perhaps you don’t buy my initial claim that man desires to sing, let alone that he desires to sing to God. The Hundredfold is an invitation—a reminder that you, who are the image of God and made to glorify God, can in fact sing, and that you should not settle for banality (the brutalist library be vanquished!). It is meant to be an encouragement, “a first salvo in the Christian reclamation of the land of imagination and song” (The Hundredfold, 46). Everyone should do poetry: read it, write it, breathe it—that is what this book is about. New Virgils will arise, along with new Chaucers, new Byrons, and new Dickinsons. You could even be one of them. Esolen’s Hundredfold is a worthy and encouraging response to David’s prayer: “Sing a new song to the Lord, for he has done marvelous deeds. His right hand and holy arm have won the victory” (Ps 98:1).

✠

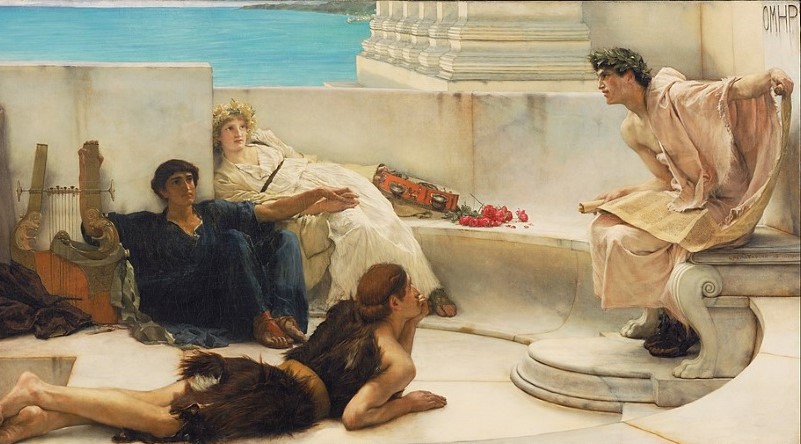

Image: Lawrence Alma-Tadema, A Reading from Homer