Sed Contra: An Essay on the Modern Culture

A “sed contra” essay is to engage a cultural concern and to address it with the help of some philosophical or theological authority.

There’s something satisfying about sweeping, pithy indictments of all human thought. Take the following claim by Karl Marx, the father of Marxism: “Philosophers have only interpreted the world differently, the point is to transform it” (Thesis XI on Feuerbach). This preference for practical change over contemplative interpretation was so important for Marx’s thought that it can be found today on his tomb. Marx’s maxim is about much more than intellectual history. It makes a bold claim about the very purpose of human life.

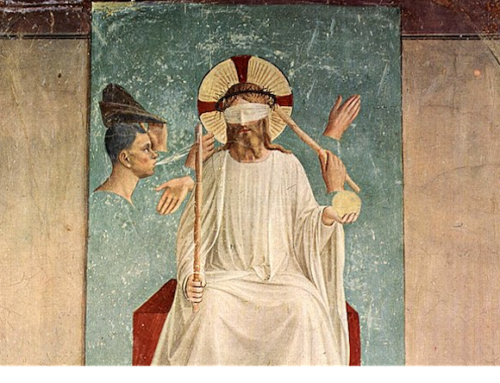

Compare Marx’s thesis with a quote from St. Thomas: “The last and perfect happiness, which we await in the life to come, consists entirely in contemplation. But imperfect happiness, such as can be had here, consists first and principally in contemplation, secondarily, however, in an operation of the practical intellect” (ST I-II, q. 3, a. 5, corp.). Happiness, including eternal happiness, is principally contemplative. Such is the common patristic reading of Jesus’s gentle rebuke to Martha: “You are anxious and worried about many things. There is need of only one thing. Mary has chosen the better part and it will not be taken from her” (Luke 10:41-42).

Efforts to “transform the world” are good and praiseworthy, so long as they make the world a better place, and not a worse one. And yet these efforts serve the one thing necessary: contemplative union with the living God.

Human life, and indeed the Christian life, are about something higher than my personal activity. Human life is something necessarily receptive. The true philosopher does not try to create the truth, he receives it from the world around him as he glimpses the order of the universe—in which human affairs are a small but important part. The Christian does not create himself, he receives from God a vision of his infinite and Triune life—now dimly through faith, and in heaven clearly, through vision. Eternal life is a matter of knowing, an activity that is above all contemplative: “This is eternal life, that they should know you, the only true God, and the one whom you sent, Jesus Christ” (John 17:3).

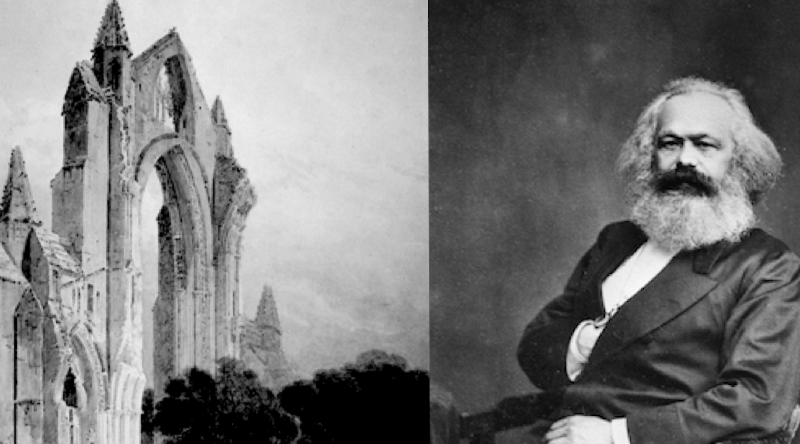

It’s easy to get caught up in a whirlwind of doing and miss out on time spent being with the Savior. Sometimes our doing has great value—the works of mercy, for example—and sometimes it is misguided, like a communist revolution. But at all times we need a reminder of the one thing necessary. I can think of no better sign than the cloister.

The monk or the nun lives a radical, walled-off separation from the world, not to run from the world but to run after a contemplative vocation at the feet of Christ. Aquinas entertains the possibility of someone giving up worldly goods for a natural love of truth (ST II-II, q. 152, a. 2, ad 3), but the monk or the nun leaves it all for the supernatural love of Jesus, to be conformed to his poverty, chastity, and obedience. To receive all from the Crucified One draws the man or woman into the cloister and keeps them there until death.

God continues to call men and women to the cloistered forms of religious life, where they live in silent prayer and intercession before his presence. Monks and nuns reveal the vocation of all religious, who have as their “first and foremost duty . . . the contemplation of divine things and assiduous union with God in prayer” (CIC 663 §1). Although there are of course other, very noble forms of religious life, the monastic vocation remains a perennial, hidden sign in the Church of the primacy of God.

✠

Images: Left: Guisborough Priory Yorkshire, decolorized (public domain), Right: Portrait of Karl Marx, John Jabez Edwin Mayal (public domain)