In 1995, a man named McArthur Wheeler robbed two Pittsburg banks after coating his face with lemon juice in order to elude security cameras. Apparently, he thought that the same property that made lemon juice work as an invisible ink would render his face invisible on a security tape. Nevertheless, police arrested him within an hour after broadcasting footage of the robberies on the news. A few years later, two psychologists used Wheeler’s robberies to showcase what is now known as the Dunning-Kruger Effect: “the skills that engender competence in a particular domain are often the very same skills necessary to evaluate competence in that domain—one’s own or anyone else’s.” In a word, the worse we are at certain tasks, the harder it is to recognize our inability. Wheeler’s undoing was his overconfidence, and he was confident in his own competence precisely because he was incompetent.

Recognizing this phenomenon can give us a sort of humility. All of us have limited experience and imagination, which curtail our getting a complete picture of the world around us—even when we don’t realize it. The less we know about something, the more difficult it is for us to recognize our own ignorance.

Nowhere is this more the case, I would suggest, than with theodicy—the problem of evil. This problem, which is in different ways familiar to all of us, asks how there can be both evil in the world and an omniscient, omnibenevolent, omnipotent God.

On the one hand, this problem creates certain logical difficulties. If there is evil in the world, it seems that God must either not exist, not know everything, not be perfectly good, or not be all-powerful. This is because it seems that if all four were true, God would not permit there to be evil in the world.

On the other hand, for our individual lives, the problem’s logic isn’t usually the primary issue. “God only permits evil to exist so that he can bring a greater good out of evil” is a true and familiar response to the problem. But even though this response gives us a way out of the logical entanglements, it still leaves us grasping when we’re rattled by deep loss, suffering, or sin. If God always brings good out of evil, what good is he bringing out of this evil? What good is he bringing out of this suffering? What good is he bringing out of this sin?

Asking these questions is not blasphemous and does not imply a lack of faith. Asking these questions is our attempt to make sense of our own experiences with evil. It is our attempt to bring good out of the evil we experience. It is our attempt to search for and imitate God.

But these questions usually put us out of our depth. “What good is God bringing out of this evil?” Frequently, we just don’t know. Because the goodness of God exceeds our limited capacities by so much, it is impossible to imagine what God is capable of bringing out of this or that evil; it is also nearly impossible to recognize just how limited our imagination really is. Each of us is limited to what we can see, remember, and dream up, unless God gives us a special insight. Thus, concluding that God cannot reap good out of a particular evil is somewhat like Wheeler coating his face with lemon juice: we would let our limited knowledge make us overconfident and presume that we know more than we do.

What we do have, however, is the cross. Christ endured the greatest suffering and permitted the greatest evil to occur in order to bring about the salvation of mankind. But then he showed us his resurrected, glorified body and, by doing so, showed us his power to bring good out of evil. Even though our inability to answer our questions about our own personal evils is itself a form of suffering, we can still follow where Christ has gone. For Christ has gone before us in suffering evil. He knows the way, even if we do not. He knows the way, even when we cannot imagine how there could be a way forward. The cross and the Resurrection show us that it is neither the greatness of any one particular evil nor any impotence on God’s end that makes an evil seem unconquerable; it is rather the limit of our ability to imagine what God can and will do.

✠

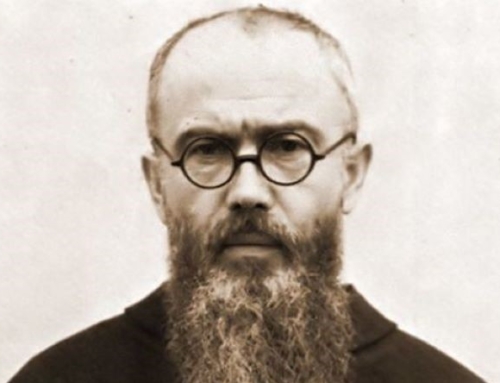

Image by Ivar Leidus (CC BY-SA 4.0)