No human relationship can ever sum up the love of God, so God uses all of our relationships to teach us about himself. He is our Father, we are his children. He is the lover, we are the beloved. We are his servants, but more than that—we are his friends. In short, every natural human relationship can be revelatory of God’s care for us, the gravity of our sin against him, and the lengths he will go to win us back.

While the fatherhood of God reaches its fullest clarity in the New Testament, God first revealed his paternity in the book of Exodus: “Israel is my son, my firstborn” (Ex 4:22). As a father, he generates, he raises, and he corrects. As a father, he has authority and inspires reverential respect. For those who have had a difficult relationship with their earthly fathers, this image can be difficult to appreciate. How is God like that guy who neglected me, perhaps even who I never knew? In response to this worry, Christ teaches, “Call no one on earth your father; you have but one Father in heaven” (Matt 23:9). Earthly fatherhood is only worthy of the name in as much as it shares in the one, true fatherhood of God.

If the fatherhood of God emphasizes his creative and providential power, the extensive use of spousal imagery through the Scriptures reveals his willingness to bind himself to us in a covenant. In the book of Isaiah, we hear the promise, “For as a young man marries a virgin, your Builder shall marry you” (Isa 62:5). The Song of Songs, too, has been read by many saints as the story of God pursuing and wooing the soul of the believer. This image reaches its most majestic expression in the promise of the book of Revelation: “the wedding feast of the Lamb has begun, his bride is prepared to welcome him” (Rev 19:7). Against this backdrop of spousal love, our sin finds an apt comparison in marital unfaithfulness. Our sin is like a married woman giving herself to prostitution (Hos 1:2). This image should give us pause. It makes all the more impressive Saint Paul’s words, “If we are unfaithful he remains faithful, for he cannot deny himself” (2 Tim 2:13).

A final relationship that God uses to teach us about his care for us is friendship. We learn about the activity of Wisdom, that mysterious figure of the Old Testament who so strongly prefigures Christ: “Passing into holy souls from age to age she produces friends of God” (Wis 7:27). Jesus tells his disciples, “I no longer call you slaves, because a slave does not know what his master is doing. I have called you friends, because I have told you everything I have heard from my Father” (Jn 15:15). Friends, as Saint Thomas Aquinas is fond of saying, share secrets (Commentary on John 15, lect. 3, n. 2016). God has told us the Trinitarian secret of his inner life, and we have been called to share in it. This generosity is what makes any betrayal—Judas’s, Peter’s, ours—so condemnable. And this generosity reveals its willingness to go to hell-harrowing lengths to regain our friendship on the Cross.

This use of human relationships to describe God’s relationship with us reveals that the whole web of human social connection is more than a tangled mess of overlapping histories. God has created us with the capacity for these relationships so that through knowing and loving each other, we shall be able to know and love God. God is more a Father than any father, more faithful than any spouse, more a friend than any friend.

✠

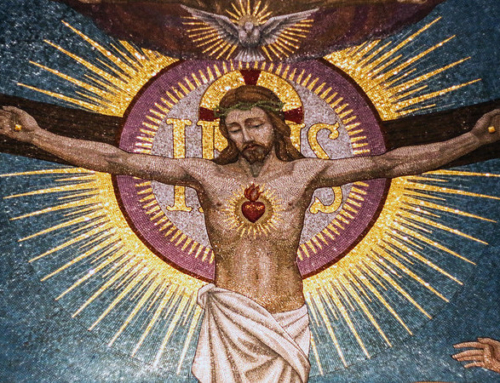

Image: Author Unknown, Anastasis, Harrowing of Hell and Resurrection of Christ