Alcuin Reid, ed., T&T Clark Companion to Liturgy. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2016.

Liturgy is central to the life of the Catholic Christian and to the activity of the whole Church. This has been the case since the days of the Apostles, and the liturgy has grown with and been shaped by the Church through the centuries. Dom Alcuin Reid has assembled a collection of essays that reflect on the role of the liturgy in the Church’s life from various perspectives, the combination of which provides a detailed image of the liturgy as a varied and dynamic entity that nonetheless points singly and directly to Almighty God.

The authors that Reid has assembled include religious, clerics, and laymen exercising their knowledge of history, theology, music, and architecture. Their contributions are organised into four parts: a discussion of liturgical theology; an overview of the history of the liturgy; perspectives on the Second Vatican Council; and assorted contemporary themes. These are followed by an encyclopedic glossary, which ranges from defining Latin terms to giving brief histories of persons and rites, and a standard index.

The individual essays give necessarily broad overviews of their subject matter, but each pauses to go into depth on a few topics, such as Easter celebrations in 12th century Jerusalem (82), a press conference given by a Second Vatican Council peritus on the term “pastoral liturgy” (349), and the architecture of Santa Susanna in Rome (443). Detailed endnotes and bibliography follow each essay, providing opportunity for further study. The tone is generally academic, but accessible. The historical section is perhaps the most susceptible to dry academic considerations, but the effect is lightened by several delightful anecdotes about medieval liturgies, such as a blessing in which the miter is said to give the bishop “a head armed with the horns of each Testament that he may appear fearsome to the adversaries of truth” (97).

Any modern study of liturgy is likely to be categorized by its approach to the reforms begun by the Second Vatican Council, and Reid both acknowledges in his introduction and demonstrates in his own essays that his own view of the reforms following the Council is a critical one. He notes that while he did seek out authors who broadly praise the liturgical reforms of the Council, only one responded, Dom Anscar Chupungco, now deceased (xviii). While Chupungco contributes two out of the four essays in the section on Vatican II, his contribution is largely overshadowed by the more traditional bent of the remainder of the book. That said, the historical section, particularly before the early modern era, delves deeply enough into the messy details of history to demonstrate clearly that the liturgy has always been in flux. For example, several essays mention the neo-Gallican rites peculiar to France which remained in use until the 19th century, indicating that the Tridentine Missal was never universally observed (e.g. 143).

The diversity of topics lends the book to a gradual, non-sequential reading. However, the essays as a whole do bring out several consistent themes. As the themes are not necessarily given explicitly by the authors, it seems that they arise naturally out of the study of the liturgy rather than from any specific plan.

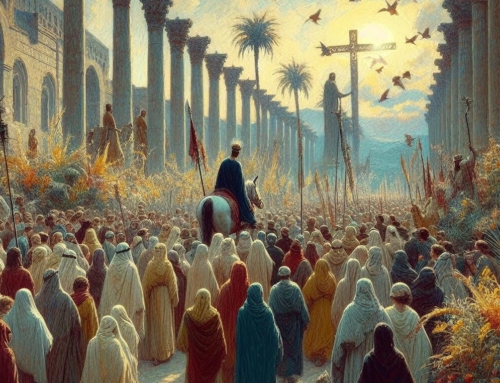

One theme stands out across all the essays, namely the primacy of active participation in the liturgy for the Christian spiritual life. This theme is addressed from various angles across topics and throughout history, but it remains a constant background to each author’s contribution. For example, the studies of the medieval period emphasize the all-encompassing role of the liturgy in culture, illustrating this with depictions of incredibly detailed and immersive popular processions. The linguists note that this influence extended to the adaptation of words and phrases from liturgical Latin into the vernacular. Historians of later periods emphasize this by contrast with spiritualities that place personal meditation above or merely equal to liturgical worship: liturgy cannot be “simply one devotion amongst others” (153). Timothy McDonnell, citing Joseph Ratzinger, gives a memorable example from the modern age. If folk music is to be used in the liturgy, the principle of active participation demands that it be truly music of the people, not the manufactured performances of the rock star (417ff). Even authors of differing viewpoints agree that the liturgy must be foremost in the practice of the faith and that for this to be a reality each praying Christian must actively participate in the liturgy.

The authors also acknowledge that some kind of reform always becomes necessary for the liturgy over time. While different authors tend in different directions, many of them observe two specific dichotomies that characterize approaches to reform. The answers ultimately lie in a both-and approach that allows for nuance and avoids false divisions. Nonetheless, different authors have reasons for favoring one side or the other of these dichotomies.

One conflict is between repudiation of the past and what Daniel G. Van Slyke calls archeologism or antiquarianism (49). On the one hand, a reform of the liturgy should look to what past generations have found valuable. However, this approach can be taken too far. If one seeks to recover the past simply because it “carries the savor and aroma of antiquity,” one becomes guilty of archeologism, which, as Pius XII described in Mediator Dei, ignores the genuine growth of the liturgy under the guidance of the Holy Spirit (49). Such an approach is further hampered by the fact that so much of antiquity is entirely lost to us. It is also possible to tend too far in the other direction, viewing all of modernity as an advance over the past, although such a view does not appear in this work.

An interesting example of a more balanced approach to the recovery of the past is provided in Susan Treacy’s discussion of the work of the abbey of Solesmes in standardizing Gregorian chant. At the time of Solesmes’ work in the 19th century, roughly three versions of chant were available: from the 17th century, from the 11th through 13th centuries, and from the 10th century and earlier. The monks of Solesmes decided to read the 13th century and earlier manuscripts together, and they rejected the modern work not because it was modern but because it was, as Dom André Mocquereau (1849–1930) put it, “a miserable caricature” of the earlier work (250).

A much more difficult question arises in the consideration of whether liturgical reform should seek to adapt the people to the liturgy or the liturgy to the people. Each view comes with its own difficulties, and both views have prevailed at different times throughout the history of the Church. Dom Prosper Guéranger’s L’Année Liturgique, an 1841 series of books with meditations on each day of the liturgical year, is an example of the kind of educational effort required to adapt the people to the liturgy. On the other hand, celebrating Mass in the vernacular is an instance of adapting the liturgy to the people. Again, it is clear that both kinds of adaptation are needed for spiritually beneficial reform, although different persons, including the contributors to this volume, lean more heavily toward one or the other.

Dom Alcuin Reid has combined a wide variety of sources into a wide-ranging reference book on the liturgy. It provides both a comprehensive introduction and plenty of direction for further exploration. Out of the diversity of backgrounds and opinions, several themes emerge which should help the reader both to think carefully about liturgical scholarship and to grow in prayer at the “summit and font” of the Church (Sacrosanctum Concilium 10).

✠

To download a printable PDF of this Article from

Dominicana Journal, Winter 2016, Vol. LIX, No. 2, CLICK HERE.