Although we spend much of our mental energy trying to overcome external obstacles to our happiness, we largely forget that our primary struggle is always with ourselves—fears, wayward loves, vendettas, and the like.

Take Bilbo Baggins, from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, as an example. After being hired by thirteen dwarves to “burgle” for them—which in this case involves aiding their quest to retake the Lonely Mountain and its treasures from a dragon—he joins the dwarves as they journey to the mountain and shares in all their adventures to that point. But then they arrive at the mountain, and Bilbo is the one they’ve hired to plod through a secret tunnel into the mountain where he knows a dragon lies, hoarding a treasure. Bilbo continues onward until he sees a growing “red glow” and hears a “rumble, as of a giant tom-cat purring.” As Tolkien describes,

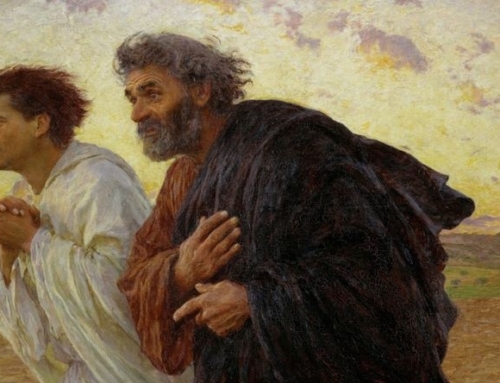

This grew to the unmistakable gurgling noise of some vast animal snoring in its sleep down there in the red glow in front of him. It was at this point that Bilbo stopped. Going on from there was the bravest thing he ever did. The tremendous things that happened afterward were as nothing compared to it. He fought the real battle in the tunnel alone, before he ever saw the vast danger that lay in wait (184).

If you think about an ordinary human being, he has a lot going on. He experiences all sorts of desires and threats, from the level of the senses up to his desire for spiritual goods. He also apprehends the evils that threaten those goods, which give rise to fear, bravery, anger, despair, sorrow, and so on.

But not all goods equally perfect us. As a consequence, lower goods can easily distract and detract from our seeking to be happy. Sometimes, a higher good entails that we risk suffering or endure loss of some kind. Because of this, our interior loves and fears often put up a fight. What we love at least appears to be good, and what we fear at least appears to be evil. The result is something like trying to catch a rabbit in a room full of mirrors or an interior shell game that can confuse and weary us until we either capitulate or lose sight of the higher good we were aiming at. What perfects us—life with God—gets lost amid all the apparent goods that present themselves to us in our heads.

Like Bilbo, we come to some point in the tunnel where we ask ourselves, before ever encountering an external obstacle: Am I really okay if I endure ridicule, physical suffering, or isolation? Am I really going to give up this vendetta against someone who hurt me unjustly? Am I actually going to face this dragon that I’ve never seen—this unknown threat that I have no clue how to handle? Often accompanying these questions: What are you doing? Are you out of your mind?

If we lose sight of this battle, then, like a chess player who spends all his energies trying to capture his opponent’s queen but loses the game, we will likely forfeit the external battle as well.

But the irony is that, although this interior battle is waged “alone,” we’re never really alone. In fact, we can never successfully wage this battle alone to overcome ourselves. Grace comes to the rescue. Grace is the Holy Spirit’s helpful presence in our souls, aiding us, comforting us, and strengthening us. Not only do we win this battle by reminding ourselves how good God is for us amid the mental webs that entangle us, but we must also call upon him to help us. Then, once this battle is won, we will look back and say to ourselves, “The tremendous things that happened afterward were as nothing compared to it.”

✠

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)