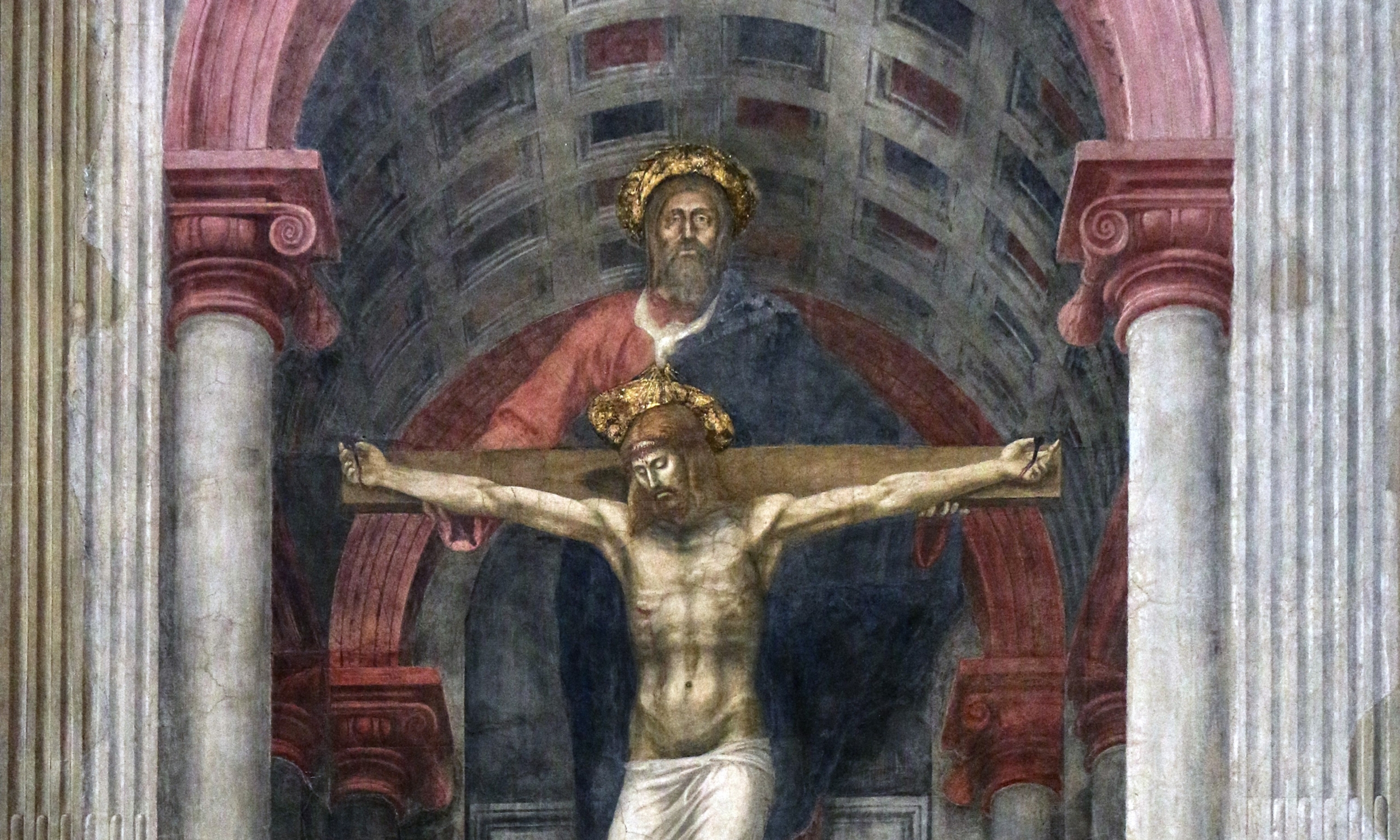

Behold the wood of the cross, on which hung the salvation of the world.

– Good Friday Liturgy

Beheld with a temporal gaze, a crucifix is a terrifying image. A gangly man, body contorted, hangs from a rugged tree trunk, secured only by nails appending his extremities to beam and post. His flesh is lashed, skull pierced by a barbed crown, side impaled by a spear. And in a spirit of decency, iconographic discretion trumps historicity, for the man was in fact naked.

For Catholics—and for many others—this image is ubiquitous, perhaps to the extent that, tragically, it can even seem banal. Another icon, blingy pendant, or statue of that passé religious figure seen countless times before. Next, please.

But to those unexposed to the Christian religion, a crucifix is strikingly repugnant. Who could possibly reverence such a travesty?

Take, for instance, the 1966 North Korean World Cup team. Playing in England, the host site, the North Korean team upset the Italians and advanced out of group play to the quarterfinal match in Liverpool. The Italians, expecting victory, previously arranged for their quarterfinal accommodations at Loyola Hall, a newly renovated wing of a Jesuit retreat center outside of Liverpool. Meanwhile, the North Koreans had made no arrangements—they did not expect to make it that far—and hence were grateful to take the Italians’ reservation.

But upon arrival, they were met with a surprise. The North Koreans, nearly all of whom had never before left their homeland, were used to sleeping in a common dormitory. At Loyola Hall, they were to stay in individual cells, which meant not only solitude and silence but also “disturbing iconography on the walls.” Worst of all, they said, was the chapel—floodlit at night and overlooked by a massive “figure of a man in pain with ‘scary nails’ in his hands and feet.” One player noted, “we had never seen these things before; they caused us to worry and fear, and we couldn’t sleep well”—which perhaps contributed to their quarterfinal loss to Portugal.

Worry and fear: precisely the goals of Roman crucifixion, an act of state-sanctioned terrorism levied upon the vilest of criminals and designed to petrify any would-be malefactors. The Romans honed the penal art they received from Egypt and Carthage, often adjusting the criminal’s posture with a horizontal block so as to prolong maximal pain and suffering, sometimes delaying death for as much as days. Indeed, crucifixion is the prime analogate of our word “excruciating,” which signifies a level of pain known only to those suspended ex cruce, from the cross.

We can thus understand why, in his First Letter to the Corinthians, Saint Paul describes the crucifixion as a skandalon—a stumbling block, a scandal, an embarrassment. Jews ask for signs, St. Paul notes, for they await the fulfillment of foretold prophecies. Greeks seek wisdom. But we preach Christ crucified, a skandalon to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles, but to those called, Jews and Greeks alike, Christ, the power of God and the wisdom of God (1 Cor 1:21-24).

Beheld with such an eternal gaze, a crucifix is the improbable but triumphant sign of God’s infinite power and wisdom over worry and fear, sin and death. Our illumined eyes, which view by faith and not by sight (2 Cor 5:7), exalt its ignominy, for it was “for us men and for our salvation,” that the Lord of hosts so stooped, only to rise in redemptive glory on the third day. At Calvary, under the appearance of total impotence, Christ’s supreme love realizes man’s supreme potential: reconciliation with the Father and eternal beatitude—the antithesis of banal.

Jesus Christ is the light of the world (John 8:12), and the cross the lamppost upon which he hangs. Thence, he casts a light unto my path (Ps 119:105), the path that leads to and through his narrow, cruciform gate. Such is the only way—our only way—to truth and life. And in his great love, he treads it again with each of us, in each of us, for each of us: day after day, unto death, into life. For I have been crucified with Christ; it is no longer I who live but Christ who lives in me (Gal 2:20).

✠

Photo by Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)