Fire or Ice? Robert Frost considers the options in one of his more famous poems:

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

Fire or Ice. Frost characterizes the end of the world in anthropological terms: flaming desire or chill hate. Having written the poem in 1920 after the First World War, Frost was well aware of the destruction that man could wreak. He also knew personally, just as we all do, how strongly the passions of desire and hate can motivate us to become agents of that destruction.

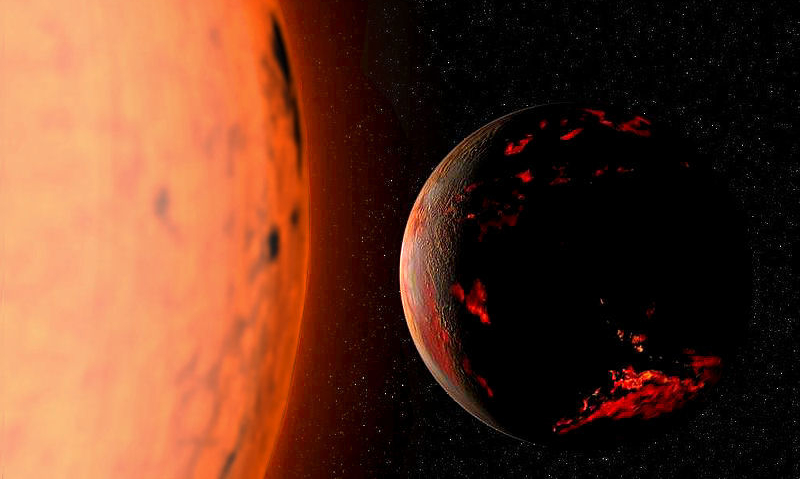

But Frost also recognizes what even a casual investigation of astronomy reveals. Whether humans cause it or not, Earth will eventually die, engulfed by an expanding sun in a few billion years—if nothing happens sooner. Even if we as a human race managed to make it to Mars and eventually ventured out of the Solar System, still, the heat death of the universe looms at the end of the line.

Reflecting on the end of the world could lead one to despair, but Christian hope points us beyond that end. Keeping that hope in mind is an excellent Lenten practice. It helps us to remember to focus on things that will really last instead of those things which are passing away. This focus helps us to live differently. When we are guided toward eternity, even the strongest passions that are normally stirred up and directed to earthly things can be reoriented toward the things which endure. Passions powerful enough to bring about the end of the world, desire and hate, can instead be directed toward personal transformation. Saint Catherine of Siena frequently takes up the image of a two-edged sword that is found in scripture and describes the two edges as love of virtue and hatred of vice. Lent is the season where we try to take up that sword and cut vice out of our lives to make room for virtue. This is, generally, an unpleasant task, even a sort of death. Just as the physical world is passing away, so must we. This passing away is not, however, a fading to oblivion, but a rebirth.

In Isaiah, God reveals his plan to create a new heavens and a new earth. In the new heavens and new earth, God promises everlasting joy and happiness to his saints. It will be a just creation. Everything in it will be ordered according to his wisdom. There will no longer be any cause for sadness or grief. When we consider God’s promises and compare the world as it is right now with what will be, we need not fear this world’s passing. By cooperating with God through our mortifications, we have already ceased to belong to the present world. How must we, then, relate to a world on fire? First, we should not let our fear overwhelm us when we see wrongly directed desires and hatred driving the world toward destruction despite our best efforts. Second, knowing what God has prepared for us, we should be strengthened by the hope that the new heavens and new earth are drawing closer.

As we watch so much of the world burning around us, it’s hard not to hold tightly to what has yet to be consumed. Our world may be fading, but it is still full of many good things which God placed in it from the beginning. We rightly love these good things, yet they too will pass away. For this reason, Lent is of such great importance. The asceticism of Lent demands that we give up the good things of the present world for the sake of the better things of heaven. Such an exchange is only possible when love casts out the fear of loss which tells us to cling tightly to what we have. Whatever we give up for his sake, Jesus has promised to give back to us thirty, sixty, or a hundred-fold. Therein lies our hope.

✠

Image by Fsgregs at the English language Wikipedia project