2020 Summer Reading Recommendations:

A Time To Die: Monks on the Threshold of Eternal Life by Nicholas Diat

One of the most defining features of the modern age, and perhaps one of the most modern features of the modern age, is its condemnation of death itself. It would be well if this were remembered by those who talk so often of its condemnation of life. For there is, indeed, a strain in the modern age that not only denies the sanctity of human life but the possibility of a dignified death as well; and like most everything else modern, one should see both denials as an outright condemnation of what it really means to be a human in via, of what it really means to be a human on a journey to God.

It is idle to belabor this point further; but to speak of the failures of modern medicine in its pursuit of prolonging vitality at the expense of one’s humanity, for instance, is not to belabor—it is merely to record. Most of what pertains to death has been struck from sight, hidden away (in nursing homes and the like) lest it remind modern man of what awaits him, lest it remind him of his pitiable state before God. Death itself is welcomed by some and feared by others, but in either case, modern man has scorned this mystery of mysteries in the name of, and for the sake of, unbridled autonomy. When life has been deemed unlivable, he chooses death; when death has been deemed unthinkable, he chooses life. He so often considers himself in via ad nusquam that he fails to see the possibility of a life lived in via ad Deum.

But anyone who understands what is really at stake in the modern age will note with interest that modern men are, from time to time, not all that modern. Behind the walls of many a monastery throughout the world, godly men and women prepare for the mystery of death as one prepares for a most welcome guest. To be sure, these godly men and women are not exempt from, or indifferent to, the human condition—for they are as fearful, tormented, and sorrowful as the rest—but they are exempt from, or at least indifferent to, a certain kind of godlessness—the sort of godlessness that obscures the reality of their state before God. They know themselves to be viatores, men and women in via ad Deum.

There is no replacing the personal experiences of these godly men and women with respect to death. There is a peculiar sort of naivety in them; a sort of childish humility and simplicity. Certain narratives of monastic life depict the aged monk not as a man who has overcome his baser passions but as a demi-god who could never have been touched by them. Such stories testify to nothing but a false notion of monastic life. For these godly men and women are indeed capable of falling, even after having lived a life bent on rising above their own wickedness. Men and women who persevere under the trials of suffering and death hardly receive reward or recognition from modern man, but modern man would do well to learn from them—to learn how to die and to die well.

Enter the recent book of Nicolas Diat, A Time To Die: Monks on the Threshold of Eternal Life (2019). In this brief work (174 pages), the French journalist and author whose writing career has become nigh synonymous with the name Cardinal Robert Sarah offers a rare glimpse inside the cloister of eight European monasteries, including the incomparable likes of Solesmes Abbey and the Grande Chartreuse. The book is not so much a narrative, as a collection of interviews with monks who have witnessed their confreres die well, and exceedingly so.

Perhaps no other author would have written it in precisely the same way, would have been as exacting in his portrayal of the monks’ humanity and as exacting in his portrayal of the monks’ mortality. A certain fine veil had to hang over all the interviews; there was nothing that Diat could do to avoid the mystery that accompanies any and all conversations about death. And it may be that only in the future will that veil be lifted, when man passes from viator to comprehensor.

✠

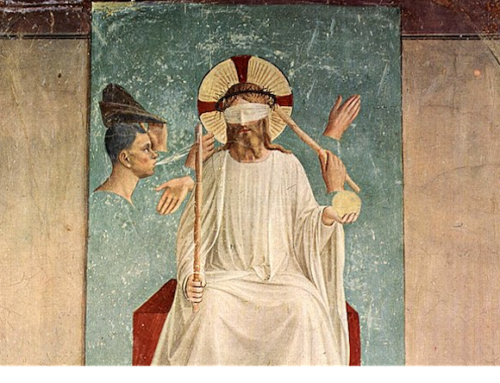

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)