Americans are notorious the world over for being doers, people who get things done. We pride ourselves on designing and creating, organizing and executing and buzzwording about—and all at maximal efficiency. We esteem ourselves for these things because they are generally good and because we are quite good at them. One need only look around.

But as with any good thing this side of heaven, we are wont to distort the importance of our doings and so idolize them. Attend a social gathering—say, a Christmas party—and frequently enough, conversation turns to one’s line of work or, if not “work” itself, other hobbies and occupations, or those of one’s children. These discussions are rarely neutral, for pride is often at stake, especially upon a first introduction. Americans are an empirical people, after all: we tend to judge others’ worth—and our own—by measurable output, whether financial, intellectual, cultural, athletic, or otherwise.

There is, to be sure, something correct about this typically American analysis. Our actions proceed from who we are. From the fullness of the heart, the mouth speaks (Matt 12:34), the body moves, and the person acts. By and large, if you want to know what kind of person someone is, you watch him act: the wise man acts wisely, while the crook acts crookedly. Our habitual actions reveal our character. You will know them by their fruits (Matt 7:20).

But amidst all of this, we can lose sight of the fact that behind all of our actions, whether good or bad, and underneath all of our habits, whether good or bad, is a more fundamental reality: an eternal soul called to supernatural life. And so we must ask, given what humans are, what kinds of things should we do, and which are really of ultimate worth? Correctly answering this equips us to navigate the Christmas party conversation, not to mention the whole rest of our lives.

Man is set above his fellow material creatures because he has an intellect for knowing and a will for loving. In heaven, these two powers are in full-tilt beatific action—maximal love-gazing upon God all the time, forever. Since God has created the human being for just that kind of action, we must find in Him the proper principle for our every deed in this life: you shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind, and with all your strength (Mark 12:30). Mind and heart, or intellect and will. Soul and strength, or being and action.

We thus discover the true metric for judging worth, whether others’ or our own: love. Faith, hope, love abide, these three; but the greatest of these is love (1 Cor 13:13). In and through and beyond our every act of designing and creating, organizing and executing, we are to be lovers—of God and of everyone else for his sake. Such is the power of divine charity, that it can transpose any good, ordinary human action into a genuine act of loving God and neighbor. Our whole life—literally everything—thus becomes an occasion for love, for real, supernatural communion with God.

Yet divine charity also remains an immense mystery, for its action is invisible, just like the One Whom it enables us to love. Which returns us to a much more profound appraisal of that typically American empiricism: For the Lord sees not as man sees: man looks on the outward appearance, but the Lord looks on the heart (1 Sam 16:7). It is the heart—an interior power—that loves. In the final analysis, it is not on account of being the best designer or creator, organizer or executor that one enters first into the Kingdom of Heaven. It is on account of being a lover of God above all things, big and small, and of all else in reference to him. Indeed, it was for this that a Child was born unto us, to live and to die in Love and to enable us to do the same—in the Christmas party conversation and in everything else.

✠

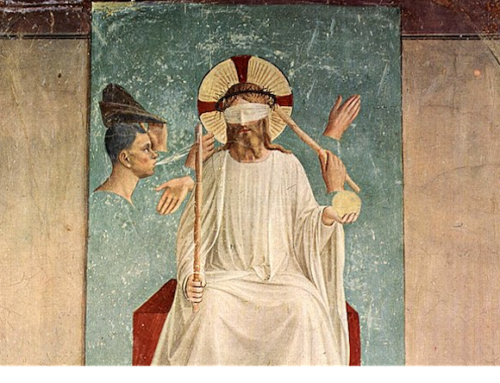

Image: Nostra Signora del Sacro Cuore, PIazza Navona (Wikimedia Commons)