I once spent a frigid night awake at a Florentine McDonald’s after getting stuck at the train station Firenze Santa Maria Novella. That part of the night wasn’t horrible. I conversed with a native Florentine who, among other things, boasted that the McDonald’s burgers there were superior to all others because they used Florentine beef. After falsifying this by trying one, I caught the 04:32 Regionale back to Bologna where I lived at the time and huddled up in the corner of a seat bleary and trying to keep warm. Naturally I felt lousy when I returned. I feebly found my way to my apartment where I shut the door, locked as always, and spent the next day in bed.

Somewhat recuperated by that evening, I had a previously scheduled dinner appointment with friends, but an apartment door lock jammed from the inside told me otherwise. After a few harebrained bids to open the door and after letting the door know how I felt, I acknowledged my entrapment within my own living space. I had slept that day an unwitting domestic prisoner snoring through the daylight hours and shackled to my abode.

This last point stirred an uneasy reflection. My self-imposed house arrest, while news to me that evening, was effected around 7:00 that morning. How long I was unaware of being a captive was troubling. There is something eerie about finding out you’ve been trapped in a space. Once I discerned my predicament by dueling with the door, I needed to get out. I had someplace to be, but I also needed to get out just because I was trapped there.

The Christian spiritual life is much like this. It is commonplace that while snoozing in various vicious habits or neglecting those things necessary to live in divine charity we think we can “leave” whenever we wish and by our own power. We only think this way because we’ve not yet tried the doors of our little self-enclosures. Yet this delusion of self-sufficiency and freedom from what really shackles us can devitalize our desire to escape by seeming to warrant complacency. The life of grace is there for us to take up by ourselves when we want it, and when the time comes we can easily remove those things in our lives that continually blot out charity.

Perhaps we stay like this for the foreseeable future. Or perhaps we try the door that should just open. It doesn’t. If we don’t repress it, how unfree we really are unsettles us. At this point the temptation is despair, but spiritual despair is as unnecessary as it is tragic. Christ, through his life, passion, death, and resurrection, bestows grace in abundance. “The very least suffering of Christ sufficed to redeem the human race from all sins,” writes St. Thomas (ST III 46.5 ad 3), and Christ suffered so much. We have particular access to this grace in the sacraments, especially in the sacrament of penance. We share intimacy with Christ in prayer: liturgical and devotional, and in the fellowship of believers that is the Church.

Eventually I was set free from my domestic prison from the outside. I escaped into the night and joined my friends for dinner. All of us experience in this life some sort of self-enclosure from which our own powers are insufficient for escaping. That is expected, but illusions of self-sufficiency should not dull our urgency to escape. No. We desire to escape, but by ourselves we lack the freedom. Thus we turn to the Lord: “where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is is liberty” (2 Cor 3:17).

✠

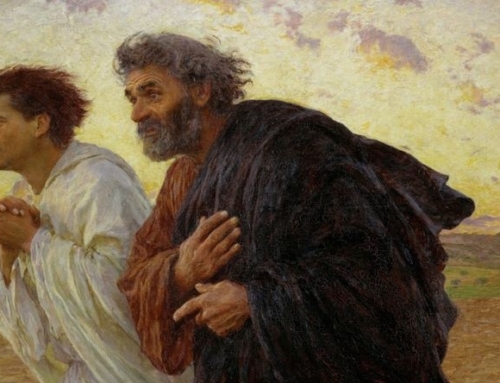

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)