My God, who hast allowed us human hopes, but who alone bestowest Christian and supernatural hope, grant, I beseech thee, by thy grace, this virtue to my soul, to the souls of all I love, and to all Christian souls. Let it enlighten and transform our lives, our suffering, and even our death, and let it uphold in us, through the disappointment and sadness of each day, an inner strength and unalterable serenity. —Prayer for the Virtue of Hope, Élisabeth Leseur

“I set myself to attack her faith, to deprive her of it, and—may God pardon me—I nearly succeeded.”1 So confessed Félix Leseur. In the tender preface appended to his wife’s prayer journal (published posthumously by Félix), he poignantly acknowledged his attempts to dissuade Élisabeth from her practice of the Catholic religion. He wrote, “In marrying I undertook to respect my wife’s faith and to let her practice it freely. But I rapidly grew to tolerate only with impatience convictions that were other than my negations; and as religious neutrality is as much of an illusion in private relationships as in public institutions, I made Élisabeth the object of my retrogressive proselytizing” (F. Leseur, “In Memoriam,” 12). And so to his wife he passed copies of the works of Strauss, Renan, Loisy and others, in his attempts to unsettle her religious convictions.

Their friends, too, offered little solace to Élisabeth. Early twentieth-century France suffered intense conflict between militant secularism and Catholic partisanship. One has only to think of the complexities of the Dreyfus Affair (broadly speaking, the trial divided the nation between pro-Catholic anti-Dreyfusards and anti-Catholic Dreyfusards) or the anti-clericalist Republican movements (in 1905 France became officially un état laïque, by law a secular nation) to conjure up vivid images of the tensions of the day. Félix—an atheist doctor engaged in work as a journalist and diplomat—lived and breathed the air of a world hostile to supernatural faith. So it was with his political and scholarly friends as well. In this circle of polemic and criticism, Élisabeth and Félix together socialized; wondrously, in the midst of this raillery and badinage, Élisabeth ascended to God.

Despite the often difficult milieu, Élisabeth set herself to study her faith. Equipping her library with the works of Aquinas, Jerome, Catherine of Siena, Francis de Sales, Teresa of Avila and many others, she amassed the intellectual ammunition to stock a little armory of her own. Soon, the home of Félix and Élisabeth contained two libraries: her Catholic collection facing his atheist annals. Élisabeth thus readied herself to articulate explanations of her faith and sought answers to the questions posed to her. She knew the value of the Church’s intellectual tradition and set herself to drinking deeply from the font of wisdom of the saints.

It was not, however, her intellectual prowess that would eventually inspire her husband to rediscover the faith of his baptism. She herself knew she could not win souls by disputation, saying,

Around me are many souls that I love deeply, and I have a great task to fulfill with regard to them. Many of them do not know God or know Him only imperfectly. It is not in arguing or in lecturing that I can make them know what God is to the human soul. But in struggling with myself, in becoming, with His help, more Christian and more valiant, I will bear witness to Him whose humble disciple I am.2

Élisabeth did not cause by way of fevered argument or dazzling exposition her husband’s conversion.3 Félix readily attested to this fact, saying, “The intellectual side, which had until then played so great and almost exclusive a part in the workings of my mind, had nothing whatever to do with my conversion. I was not affected by study, or reading, or exegesis, or apologetics, or theological knowledge, for, in fact, I possessed none.”4 For Félix, the emphasis on the role of divine grace in his conversion cannot be understated. He continued by saying, “It was brought about by something extraneous, higher, stronger, and superhuman, […] in other words, by God’s grace” (F. Leseur, “Introduction,” 6).

After Élisabeth’s death—she suffered immensely from the cancer that claimed her life—Félix discovered her spiritual diary. Upon reading her journal, he saw, for the first time, the hidden, spiritual dimension of the woman he so dearly loved and, thereby, came to love her truly. The question then arises, if Élisabeth’s journal did not make an intellectual argument which convinced Félix of the existence of God or His Providence which governs the universe, what effect did it have? If not by theological argumentation, can we really say Élisabeth was a cause of his conversion? An examination of penance, Élisabeth’s devotion to the saints, and the theological virtue of hope will illuminate—if only vaguely—the mystery.

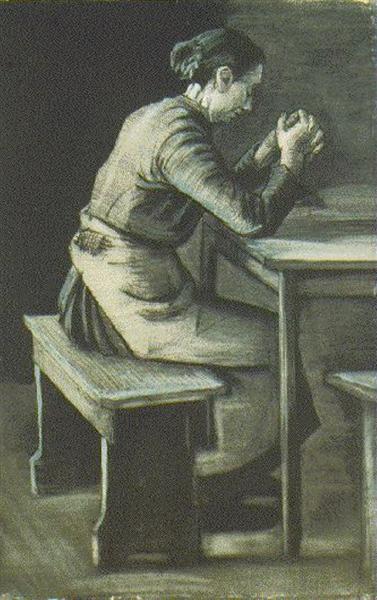

Penance and Merit

Élisabeth’s extraordinary life of penance and mortification offers one answer to the question. Repeatedly in her Journal, Élisabeth notes her desire to undertake various reparations on behalf of others. First and foremost, she begged this grace of the Lord Himself. Élisabeth prayed saying, “Give me the grace of being—by prayer at least, and by suffering—Thine instrument with souls, those who are dear to me, and those whom I do not know but who need my humble intercession with Thee” (É. Leseur, Journal, 134). Élisabeth possessed an admirable, indeed exceptional, hunger for souls, but she ultimately knew such hunger was only quenched according to the workings of God’s own economy of grace.

In cooperation with the dispensation of grace, Élisabeth set her mind to penance. She wrote,

We are all bound to do penance; none of us has a right to dispense himself from it, for none of us is without sin or without great need of expiation. For a soul, however, that is called to walk in the way of Christ’s counsels, penance and prayer are the most important works, the most efficacious means of salvation for the soul herself and for others, the most useful instruments in the task of reparation to which chosen souls are called.5

Élisabeth’s mortification was far from extreme or ostentatious. She frequently commented how it must remain secret, hidden, as well as prudent (e.g., É. Leseur, Spiritual Life, 73). Nevertheless, we must underscore the intentionality of her penance. She wrote, “In a special way, with pious persistence, I will often offer for that [specially chosen] soul part of the day’s activities or sufferings and will pray and practice mortifications for it” (É. Leseur, Journal, 137). Time after time in her writings, Élisabeth indicated her daily acts of prayer and offerings which were marked for others.

These prayers and mortifications—true acts of the virtue of penance—were often offered particularly for Félix, though Élisabeth certainly included many of their friends in her little collection of souls. She tells us in her Journal about “how many prayers, spoken or implied, have gone out from those depths of the soul that He alone knows, asking for light and for true life, the inner life of the soul for all those I love, for him [Félix] whom I love more than all” (56). Élisabeth frequently offered whatever suffering she had to endure, as well as acts of charity for the poor and the sick, for those souls “dear” to her.

Consider, however, that when St. Thomas Aquinas treats of the virtue of penance, he treats penance as chiefly for the soul undertaking it (Summa Theologiae III, q. 85, a. 1). Properly speaking then, penance is sorrow for one’s own sins. As a virtue, penance consists of cultivating the interior disposition of heart wherein one turns to God and manifests hatred for past sins. Acts of reparation are then undertaken, as justice demands, to make satisfaction to God for sins committed (ST III, q. 85, a. 3). Of course, between God and man, justice only exists analogously since, “in certain cases perfect equality cannot be established, on account of the excellence of one, as between father and son” (ST III, q. 85, a. 3, ad. 2). Ultimately, the acceptance by God of man’s penances and acts of reparation hinges on His mercy and goodness, since man is incapable by his own works of rendering perfect satisfaction.

St. Thomas’ account of the virtue of penance thus lays the groundwork for a theological consideration of what precisely occurs when a Christian undertakes acts of reparation for another. Of course, the ultimate, perfect act of reparation belongs to Christ. Only God can offer the first grace of redemption (since the indwelling of grace is a gift freely given by God), so only Christ can merit the first grace of a man’s conversion (that is, granting sanctifying grace). Élisabeth knew this, and put it this way in her works: “Grace alone can bring about a conversion; without it we can do nothing for a soul” (É. Leseur, Journal, 223). Christ is the one mediator who stands, as it were, between heaven and earth (1 Tim 2:5), and Christ alone merits condignly. Whereas Christ’s perfect merit completely satisfies in justice the debt of sin, we—imperfect as we are—merit congruously, that is, out of an abundance of God’s grace.

It would not do, then, to call Élisabeth the savior of Félix, strictly speaking, as Christ properly was his savior. If our account were to stop there (as many Protestant understandings of grace do…), this would be a very unsatisfactory and shallow explanation for the role Élisabeth seems to have played in Félix’s conversion. St. Thomas affords a deeper and more profound view of things with his theological view of congruous merit. Whereas only Christ can condignly merit the first grace of salvation, one person can still contribute to another’s salvation. In one of the most eloquent moments of the Summa, St. Thomas teaches, “One may merit the first grace for another congruously; because a man in grace fulfils God’s will, and it is congruous and in harmony with friendship that God should fulfill man’s desire for the salvation of another” (ST I-II, q. 144, a. 6). In this way, in friendship one might offer meritorious acts of penance for another.

In the theology of Thomas Aquinas, to love a friend with the true love of friendship is to see him as another self. As such, we may then say there is a kind of union of hearts wherein one draws the other to Christ. Through this lens we ought to view Élisabeth’s 1911 pact with God for the soul of her beloved. She wrote,

Oh yes, my God, I must have it, Thou must have it, this straight, true soul; he must know thee and love Thee, become the humble instrument of Thy glory, and do the work of an apostle. Take him entirely to Thyself. Make of my trials, my sufferings, and my renunciations the road by which Thou shalt come to this dear heart. Is there anything that belongs to me alone that I would not be ready to offer Thee to obtain this conversion, this grace so longed for? My sweet Savior, between Thy Heart and mine there must be this compact of love, which will give Thee a soul. (É. Leseur, Journal, 175)

Of course, the will can always resist Christ, which is why St. Thomas warns, “Sometimes there may be an impediment on the part of him whose salvation the just man desires” (ST I-II, q. 144, a. 6). This was the case with Félix. Not until after Élisabeth’s death was he able to be open to the graces that were being stored up, as it were, for him.

Communio Sanctorum

Perhaps Élisabeth’s greatest suffering—greater even than her recurring hepatitis or the pains of her cancer—stemmed from the lack of Christian friendship in her life.6 Élisabeth often resolved to show greater amiability or improve her self-restraint among those who attacked her faith. In one place, she wrote, “I must nevertheless know how to make myself all things to all men and interest myself in things that sometimes seem childish, and sadden me by their contrast with my own state of mind. Often people are like great children, but Jesus has said that what is done for children is done for Him” (É. Leseur, Journal, 86). Is it any surprise then to find that Élisabeth would find great consolation in the communion of saints?

After suffering the death of her sister—one of her few Christian friends—Élisabeth received consolation in the celebration of the Feast of All Saints. She wrote, “This is a sweet feast, the feast of those who already live in God, those whom we have loved and who have attained to happiness and light; it is the feast of eternity. And what a fine idea to make the feast of the dead follow so soon!” (É. Leseur, Journal, 101). The principle of connection—the fittingness, if you will, which becomes for Aquinas the root of congruous merit—comes alive in Élisabeth’s experience of the saints. As she said, “Not one of our tears, not one of our prayers is lost, and they have a power that many people never suspect” (É. Leseur, Journal, 101). While, as we will later see, our hope must first be in God—desiring to be with Him for eternal life—St. Thomas teaches that one can hope in another man as a helping agent, in other words, as an instrumental cause. He writes, “It is in this way that we turn to the saints, and that we ask men also for certain things” (ST II-II, q. 17, a. 4). In this sense, then, we can see how hoping in and entrusting our prayers to others, particularly the saints, help carry ourselves and our petitions to God.

Élisabeth demonstrated her devotion to the saints in many ways throughout her life. We have already mentioned their literary works which graced the shelves of her library. Additionally, she inscribed on the front pages of one section of the manuscript of her Journal a prayer titled “Litany to Obtain a Conversion.”7 While reading it, one can sense the fervor with which she must have prayed its words, especially for the soul of her Félix. To these saints, including Dominic and Francis, Mary Magdalene and Monica, Élisabeth entrusted her most sacred prayer.8

Christian Hope

In a particular way, hope animated the spiritual life of Élisabeth Leseur. While charity holds pride of place among the theological virtues—even for Élisabeth, charity impelled her to undertake her good works and acts of penance—her life offers a vivid example of someone marked particularly by hope. Properly speaking, hope manifests confidence in the attainability, by God’s grace, of heavenly beatitude. In her own words, Élisabeth explained the meaning of hope, saying,

Hope is supernatural, a force given by God. It throws light upon life and makes us understand it, and suffering, and death, which is only a continuation of life, and all the truths that concern life after death. It puts us into closer union with God, and extends our view into that wonderful region of souls which faith first opens to us, and which charity allows us to penetrate fully.9

Hope drove Élisabeth’s desire to constantly seek improvement in life. Her Journal, filled with resolutions to cast off her sins and steadfastly strive for perfection, is one whole testimony of hope. Élisabeth demonstrated the great truth that to hope is to be in contact with God through the will in God’s action of helping souls in His goodness and mercy.

Hope moves or stretches a soul toward a good that is difficult to attain. The greatest good is, of course, God, which is why hope involves above all else the soul seeking the future happiness of heaven.10 Consider how Élisabeth proclaimed that “we ‘can do all things in Him who strengthens us.’ Creatures of weakness, we carry infinite Strength within us, and in the depths of our souls shines the Light that is never extinguished. How should we not rejoice, in spite of all, with a supernatural joy, when we have God for life and for eternity?” (É. Leseur, Journal, 226) What a personal confession of hope!

But the theological virtues in themselves are expansive things, powerful forces which broaden the horizons of human desires and destiny. It is no surprise then to see that hope can, as it were, billow over and pour out beyond the rim of a single Christian soul. Recalling St. Thomas’ beautiful theology of friendship, we can see how hope can be placed for another. Aquinas tells us, “if we presuppose the union of love with another, a man can hope for and desire something for another man, as for himself; and, accordingly, he can hope for another’s eternal life, inasmuch as he is united to him by love” (ST II-II, q. 17, a. 3).

Such was the love Élisabeth had for Félix. She wrote,

I thirst for sympathy, to bare my soul to the souls that are dear to me, to speak of God and immortality and the interior life and charity. But the human soul is so subtle and delicate that it must feel the same notes resonating in another of those divine instruments before it can sound its own. The perfect union of two souls—how beautiful a harmony that would make! With him I love best in the world, let me one day make this harmony, O my God! (É. Leseur, Journal, 62)

Élisabeth loved Félix through God and suffered knowing that he could not return her love. Her heartfelt hope for his conversion became a principal feature of her spiritual life, dominating her prayer, fueling her acts of charity, and motivating her quest for Christian perfection.

Conclusion

More than others I love these beings whom divine light does not illuminate, or rather whom it illuminates in a manner unknown to us with our restricted minds. There is a veil between such souls and God, a veil through which only a few rays of love and beauty may pass. Only God with a divine gesture may throw aside this veil; then the true life shall begin for these souls. (É. Leseur, Journal, 54–55)

Élisabeth Leseur died in the arms of her beloved husband, Félix, on May 3, 1914. During the course of her last years—years of great suffering—Félix conceded much of his hostility toward the Catholic faith, principally because he was moved by the comfort her faith brought to her. After Élisabeth’s death, Félix, devastated by her loss, discovered her prayer journal and learned from its pages that she had offered for the sake of his soul innumerable prayers, acts of charity, and the pains of the disease which claimed her life. At Lourdes, while visiting the grotto and fumbling to pray the words of the Rosary, Félix received the gift of faith. He returned to Paris, where he was reconciled to the Church, and after publishing Élisabeth’s journal, Félix entered the novitiate of the Order of Preachers. In 1923, Félix (now frère Marie-Albert) was ordained a priest and exercised various Dominican priestly apostolates for nearly thirty years. His priesthood was particularly marked by his teaching about holiness in marriage and redemptive suffering.

“Through the uncertainty of the future of those I love, and in spite of suffering and the absence of a life such as I dream of, [I] anchor myself firmly in God” (É. Leseur, Journal, 78). This and many other acts of hope express the confidence Élisabeth Leseur placed in God’s mercy and goodness. By undertaking voluntary acts of penance and offering her involuntary physical suffering, she undoubtedly confided unto God a multitude of merits, to be dispensed by Him, according to His providential plan, for those souls so very dear to her. Through the mysterious bonds of the communion of saints and by her conviction and assurance in the difference prayers make, Élisabeth encourages our own expectations. Finally, her clear understanding and demonstration of the constancy of supernatural hope—far greater than human optimism which indubitably wanes and fails—offer testimony to even the darkest fears of the spiritual life. Even while recognizing the true role one Christian may have in the conversion of the soul, we, like Élisabeth before us, must ultimately pause in awe of the mystery of Divine action. Like her, we must cling to the crucified Lord, knowing that “the chasm between souls can only be filled by God” (É. Leseur, Journal, 232).

To download a printable PDF of this Article from

Dominicana Journal, Summer 2015, Vol LVIII, No. 1, CLICK HERE.

Endnotes:

1 Félix Leseur, “In Memoriam,” in Élisabeth Leseur, My Spirit Rejoices (Manchester, NH: Sophia, 1996), 13.

2 Élisabeth Leseur, My Spirit Rejoices (Manchester, NH: Sophia, 1996), 51. This source is noted elsewhere as Journal.

3Not that she was per se incapable of doing so. A letter to a friend’s husband, M. Félix Le Dantec, demonstrates her keen ability to challenge philosophically the logical consequences of atheism. See “Letter XCIII” in Élisabeth Leseur, Selected Writings, edited by Janet K. Ruffing, RSM (New York: Paulist, 2005), 219–221.

4 Félix Leseur, “Introduction,” in Élisabeth Leseur, The Spiritual Life: A Collection of Short Treatises on the Inner Life (London: Burns, Oates and Washbourne, 1922), 5.

5 Élisabeth Leseur, The Spiritual Life: A Collection of Short Treatises on the Inner Life (London: Burns, Oates and Washbourne, 1922), 72.

6 Consider her words: “Bitter suffering of an evening spent in hearing my faith and spiritual things mocked at, attacked, and criticized. God helped me to maintain interior charity and exterior calm; to deny or betray nothing, and yet not to irritate by too rigid assertions. But how much effort and inner distress this involves, and how necessary is divine grace to assist my weakness!” (É. Leseur, Journal, 148).

7 Élisabeth’s Litany is printed as an appendix to this article.

8 Élisabeth also begged prayer of the Blessed Virgin at Lourdes (ca. 1912). Félix was moved by the scenes there, especially by her prayer. After her death, it was at Lourdes that Félix would muddle through the Rosary and implored Our Lady for the gift of faith.

9 Élisabeth Leseur, “Treatise on Hope,” in The Spiritual Life, 84.

10 “I shall have all eternity in which to contemplate Him whom my soul adores, to unite myself to Him, and to pray” (É. Leseur, Journal, 193).

Appendix

Litany to Obtain a Conversion

as Inscribed in the Spiritual Journal of Élisabeth Leseur

These all look to thee, to give them their food in due season. When thou givest to them, they gather it up; when thou openest thy hand, they are filled with good things. — Ps 104:27-28

The Lord is good to those who wait for him, to the soul that seeks him. — Lam 3:25

Lord, have mercy upon him (her).

Christ, have mercy upon him.

Lord, have mercy upon him.

Christ, hear us.

Christ, graciously hear us.

God the Father of heaven, have mercy upon him.

God the Son, Redeemer of the world, have mercy upon him.

God the Holy Spirit, have mercy upon him.

Holy Trinity, One God, have mercy upon him.

Holy Mary, pray for him.

Holy Mother of God, pray for him.

Holy Virgin of virgins, pray for him.

St. Michael, pray for him.

St. Joseph, pray for him.

St. Joachim and Anne, pray for him.

St. John the Baptist, pray for him.

Good thief, pray for him.

St. Peter, pray for him.

St. Paul, pray for him.

St. Stephen, pray for him.

St. Augustine, pray for him.

St. Dominic, pray for him.

St. Francis, pray for him.

St. Ignatius Loyola, pray for him.

St. Mary Magdalene, pray for him.

St. Monica, pray for him.

St. Teresa, pray for him.

St. Catherine of Siena, pray for him.

St. Elizabeth, pray for him.

His (her) holy patron [N.], pray for him.

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, spare us, O Lord.

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, graciously hear us, O Lord.

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy on us.

Christ, hear us.

Christ, graciously hear us.

PRAYER

Grant, we beseech Thee, O Lord, to Thy faithful people forgiveness of their offences and true peace, that, being cleansed from all their sins, they may serve Thee in peace of mind with holy confidence. Through our Lord Jesus Christ. Amen.

We witness conversions for which we cannot account. Grace often works very slowly. We may trace the successive stages in the soul’s progress towards truth, but there is always a starting-point that we cannot grasp, a sudden movement of grace before which there is apparently nothing. —Louis Veuillot