2020 Summer Reading Recommendations:

The Reed of God by Caryll Houselander

For most of us, we cannot access the masterful and beautiful Latin of Augustine’s Confessions except by way of the English translations of an R. S. Pine-Coffin or a Frank Sheed. Such is the case for the great majority of Christian spiritual works penned in languages other than English. On the other hand, when we encounter a text composed in English, we should be doubly grateful: not only have we the benefit of one more spiritual guide, but we have unmediated access to his or her words. Such should be our joy in reading Newman, Benson, Tolkien, Lewis, Sheed, Sheen, or Merton, some of whose books we have already reviewed this summer. I would like to propose one more 20th-century English “classic”: Caryll Houselander’s The Reed of God (1944).

Caryll Houselander (1901–1954) has been called a “mystic” by many because of the three visions she received during her childhood and teenage years. In all three visions, she says, “I ‘saw’ Christ in man” (A Rocking Horse Catholic, 137). In the first, she saw Christ in a particular person. In the second, she saw Christ in a particular sort of person. The third and final of these visions (not unlike Thomas Merton’s vision while standing on the corner of Fourth and Walnut) is what ultimately led Houselander back to the Church after she had strayed from the fold because of the scandalous behavior of her fellow Catholics: for several days, she saw Christ in everyone she encountered.

Houselander’s The Reed of God contains some of her mature reflections on the truth of Christ’s presence in man, a reality she considers in light of Our Lady, who was the first to bear Christ. Christ came to be “in her” in a privileged way following her act of faith in God’s divine plan. Mary, however, does not become distant from us because of her unique role in salvation history. “It is Our Lady,” says Houselander, “and no other saint—whom we can really imitate” (18). While all other saints have very special and particular callings, “the one thing that [Mary] did and does is the one thing that we all have to do, namely, to bear Christ into the world” (18). From this principal thought, Houselander launches into an extended reflection on the few moments of Mary’s life we know of from Sacred Scripture, the Liturgy, and the Tradition of the Church.

This wartime book, which is a collection of Houselander’s essays and poems, is short. The reader can easily pick it up and set it down as time permits. In this regard, it is excellent material to pray with during a holy hour or on the go. Thumbing through it can be like thumbing through the decades of the Rosary: you can pray one or all 20 at any time or pace. Today you can meditate on Mary’s fiat and the Christ hidden within her. Tomorrow your contemplation can become “active” as you seek the lost Child with her (147 ff). Regardless of which Marian moment Houselander considers, she never strays from her primary theme of Christ’s presence, nor does she venture far from the work-a-day world of the average Christian. Her prose and poetry are earthy and incarnational.

To be filled with God’s presence, one must be empty. The requisite emptiness, however, is not “formless,” says Houselander, but like the virginal emptiness of Our Lady. “It is emptiness like the hollow of a reed, the narrow riftless emptiness, which can have only one destiny: to receive the piper’s breath and to utter the song that is in his heart” (21). I recommend to you The Reed of God and pray that it serves as an aid in preparing your own soul to receive the Piper’s breath.

✠

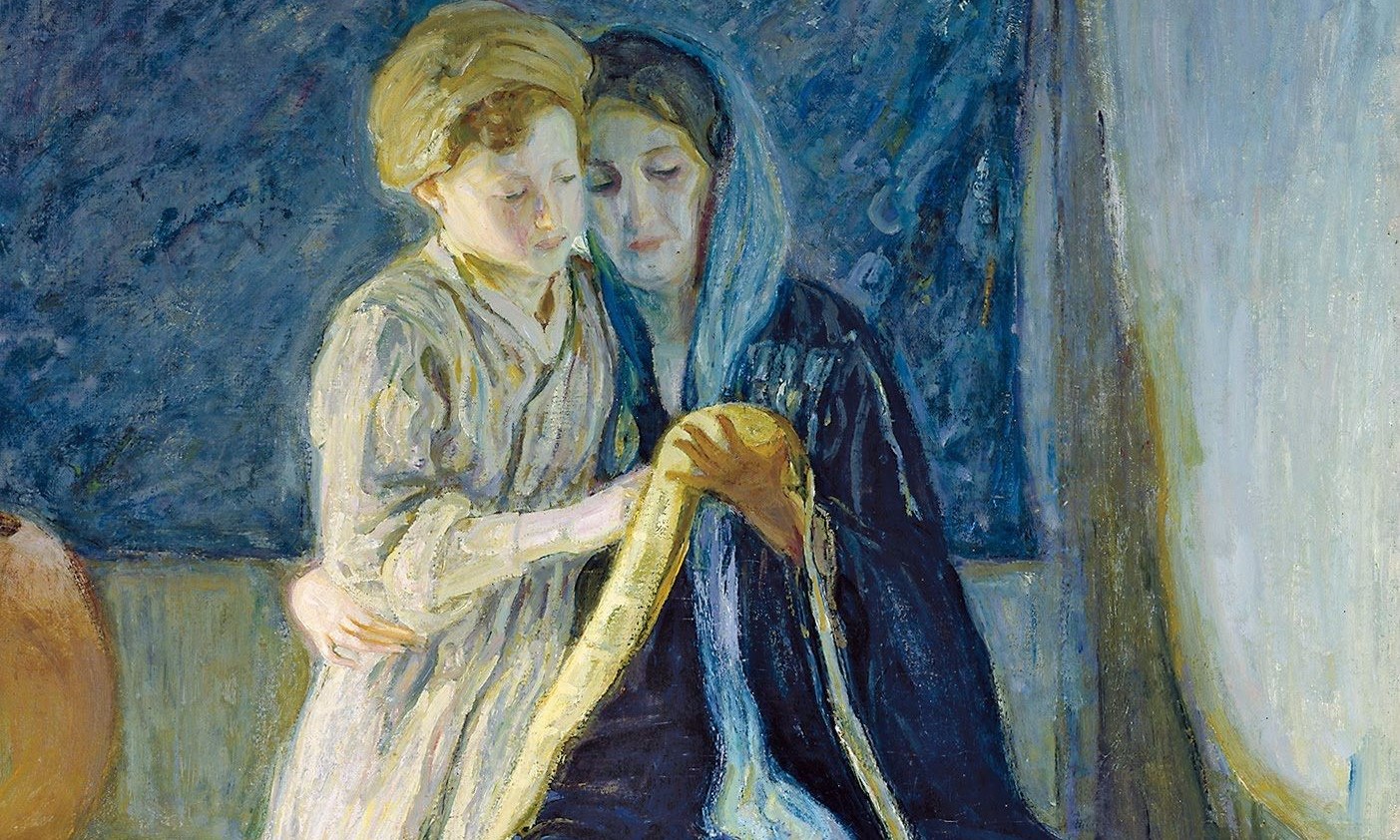

Image: Henry Ossawa Tanner, Christ and His Mother Studying the Scriptures